Contents

INTRODUCTION

It was the end of a long day. The sun was setting in the evening sky, its warmth making the red brick bell tower glow orange. It was undoubtedly a beautiful little church, its neatly trimmed lawns and pansy beds kept meticulously by the nuns from the adjoining convent. The old chestnut tree, broad and tall, had seen the faithful pass by to pray, day in and day out for many, many decades. And Christ hung from his cross above the doorway looking down onus as we peered through the locked gates. Christ and the chestnut tree had seen other things too.

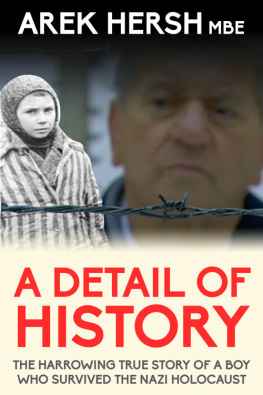

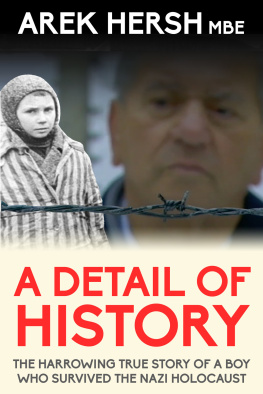

Arek Hersh was only thirteen years old when he was brought to the little Polish Catholic church in Sieradz. Along with his mother, older sister and brother, aunties, uncles, cousins and members of the Jewish community, he was herded in amongst the pews to await his fate. Arek decided to leave the building to beg for water for his family. As he entered the courtyard, he was ordered to join a group selected to work elsewhere. From the moment he stepped out of the church, he never saw his family again. The next day they and all one thousand, four hundred Jews locked into the church were filed out of its doors, deported to Chelmno and murdered.

Areks story of survival combines the intensely tragic events of a family totally destroyed by the Nazis policy of mass murder and the intimate details of a community and of people needlessly wasted by these events. If the events he described were a mere detail of history to the Nazis, to the Jewish community and to all who care to stop and think, this remains one of the most challenging moments in the history of the world. Arek Hersh, in his understated and clearly written narrative, spells out just how tragic this was. From his description of life in his hometown Sieradz, to his long journey through the ghettos and camps, this little boy becomes a man who should never have grown up so quickly.

And yet as just a little boy, he makes decisions which save his life over and again. For those who look for survival in armed resistance, take a second look at this little boy and how at times, yes, fate was on his side; but also how often he instinctively manipulated the circumstance to his own advantage. In the end, as fate, chance and pure determination would have it, Arek survived. His family, his community and his civilisation did not.

Our little group huddled together outside the church in Sieradz, listening intently as Arek told his story, locked out of the gates that once locked him in. And the sun went down, the night was cold and the church was grey once more.

Dr. Stephen D. Smith

In memory

of my mother Bluma and father Szmuel ,

sisters Mania , Itka and brother Tovia,

and my little Dvora.

Deprived of life.

DEDICATION

My wife Jean,

my daughters Susie, Karen and Michelle.

The new generation.

GLIMPSES OF CHILDHOOD

Memories of a normal world

Sieradz was an army garrison town with a population of eleven thousand six thousand Christians and five thousand Jews. The Jewish community was mainly composed of artisans and shopkeepers. It was set in rural surroundings, with forests on its horizons and fields of rapeseed shining like gold in the summer sun. It was a peaceful place, the River Warta passing its outskirts, and local history boasting that Queen Jadwiga of Poland had once had a castle here. On the corner of our street, Ulica Zamkowa - Castle Street - stood a building with underground passages which led to the castle.

Few strangers came to Sieradz except on market days, when peasants in national costume clattered through the cobbled streets in their clogs. They came regularly to sell livestock, butter, eggs and fruit. When columns of soldiers carrying guns passed by on their way to manoeuvres, my friends and I used to march behind the columns, carrying pieces of wood on our shoulders in place of guns. We used to watch, in admiration, the ceremony of swearing allegiance to Poland, held in the market square with lines of infantry and cavalry all lined up in uniform.

I was born in 1928, the fourth in a family of five children. The eldest was my sister Mania, a dynamic, intelligent and ambitious girl, who at the age of fifteen went to live in Pabianice with my Uncle Benjamin and Aunt Hela as there were more opportunities there for her than there were in Sieradz. Next came Itka, my other sister, a kind, quiet, studious girl, very like my mother in nature, who enjoyed the performing arts and loved to go hiking in the hills. My brother Tovia, four years older than me, was tall and blond, very Scandinavian-looking, and he was a keen sportsman with a good sense of humour. The only child in our family younger than myself was little Dvora, who tragically died of complications after contracting whooping cough at the age of three.

Dvora did not spend all three years of her short life in Sieradz, but in a town called Konin, where we lived for five years from 1931 to 1936, moving there when I was two. The reason we lived there was to be near my grandmother, Flora Natal, my mothers mother, who lived with my Aunt Salka, her husband and their three children. Flora Natal was a fiercely independent woman in her seventies, who earned her living from breeding, fattening and selling geese. Floras own mother, my great-grandmother, Mindl, had lived till she was one hundred and seven years old.

Because of Dvoras tragic death, one of my earliest memories is of her funeral. I remember the hearse arriving outside our house in Piaseczna Street, the horses draped in black, the driver sitting in front. I remember my sisters body being put into the hearse, then the funeral cortge proceeding up the road, my parents supporting one another in their grief. My sisters walked either side of my parents, whilst Tovia and myself walked behind. I remember the mourners clearly, the men in their black coats and hats, the women in their fox-fur collars, some with shawls over their heads. I remember, also, two beggars walking beside us, all the time rattling their tins, pleading for money. The funeral procession slowly passed by the park where Dvora and I used to play. It was autumn, so the trees and the ground were covered in golden leaves, the birches swaying to and fro in the breeze. We arrived at the cemetery gates, then passed through them to little Dvoras newly dug grave. The path was narrow, the tombstones on both sides inscribed with Yiddish, Hebrew and Polish. As the Rabbi gave a eulogy prayer, committing Dvoras body to the ground, I stood and wept, brokenhearted.

We were a very close, loving family. I respected my parents greatly. My father, Szmuel Jona, was a knowledgeable, even wise man. We were orthodox Jews, faithfully following all the Jewish laws and traditions. Each week my father took Tovia and I to the synagogue. He was a boot-maker by trade, and was kept busy making officers boots - so busy sometimes, in fact, that he had to employ two people to help him.

My father and mother were both very modern in outlook. They loved dancing and won several competitions. My father was a great believer in socialist ideals, and was very interested in world politics, history and psychology. Often he used to take me to the theatre to listen to political speakers of every persuasion. However, if he did not agree with them he stood up and told them so. He liked to speak his mind and make his point of view heard.

Though he was kind and had a good sense of humour (a trait inherited by Tovia), he was also a great disciplinarian. I remember once he caught me playing cards with some friends, and he took me home and lectured me on the evils of gambling. He never had to resort to violence to make us obey his word, but nevertheless obey we did, both out of respect for his viewpoint and out of fear of his disapproval.

Next page