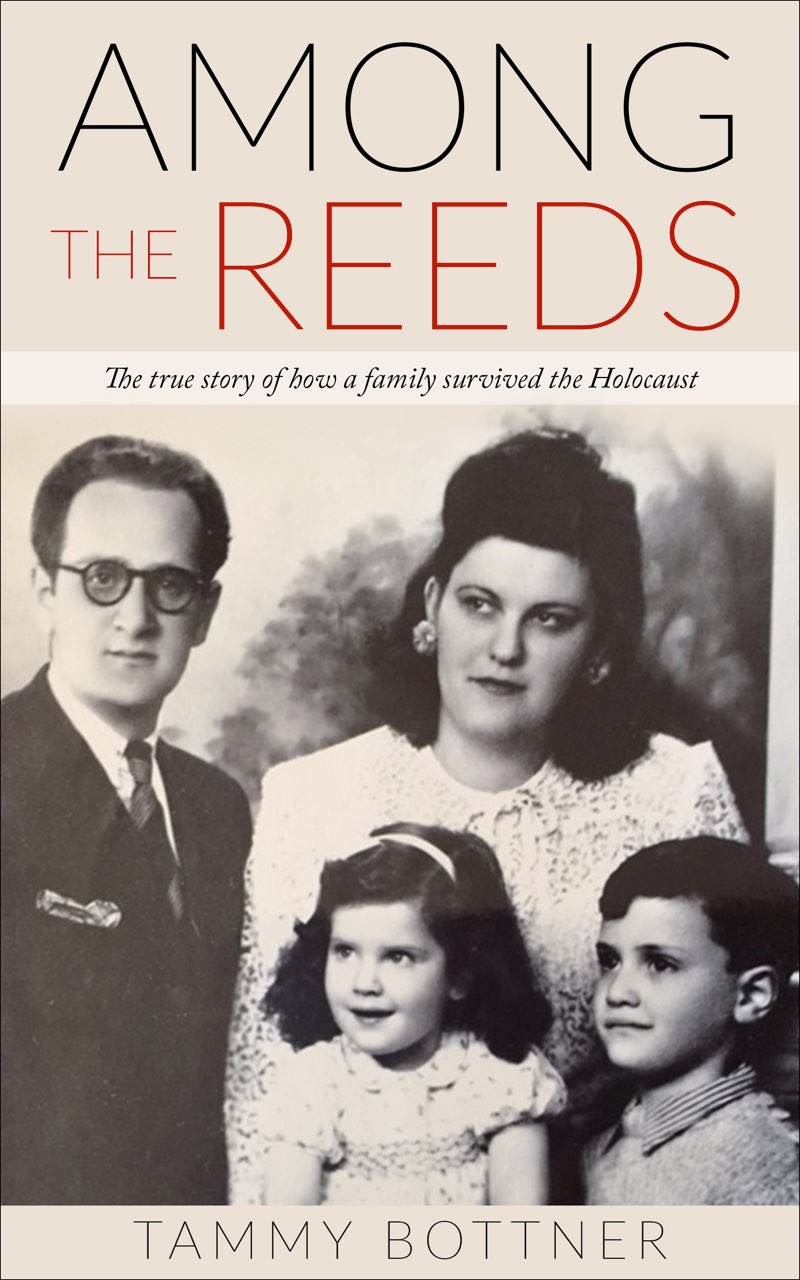

To my Dad, Al (Bobby) Bottner, and my Aunt Irene, whose childhoods were snatched from them too soon, and to Uncle Nathan, Aunt Shoshana, and Aunt Inge, for their remarkable resilience. And especially to my grandparents Melly and Genek, who had the courage to make unthinkable choices. The world can finally hear your story.

And also to the six million lost souls whose stories will never be told.

Prologue

Tammy, Newburyport, Massachusetts

It was the spring of 1997, and I had a newborn baby. He had arrived ten days after his due date, pronounced healthy, and after four days at Newton Wellesley Hospital his father and I drove him home, me sitting beside him in the backseat because, like every new mother, I was worried he would stop breathing back there and who would know? But I only did that the one time, then I sat up front like a normal person, confident Ari would survive the car ride. I really was not an overly anxious new mother. As a pediatrician I had more experience than most new moms. I could see Ari was a strong and robust baby.

We had just moved into a little carriage house in Newburyport, and had fixed up the smallest bedroom as a nursery. Aris room held a light-colored wooden crib and changing table and a pretty lamp his aunt had painted for him, and sported a good-sized window which looked out onto a leafy street. Danny was working as a psychiatrist in a local practice, and I had four months leave before I would be starting work in a pediatric practice. We were newly settled in a lovely community. Everything was good.

Yet I was terrified. And I dont mean just the regular oh my God I have a newborn what do I do type of terrified. I had already taken care of hundreds of newborn babies, many of them premature or sick. Feeding and caring for my sturdy little son was not difficult for me. My husband, Danny, was a bit scared in that way, but for me even the waking up at night to feed baby Ari was a cakewalk compared to the stress-filled, sleep-deprived years of my residency.

No, I was terrified because I was caught in a waking dream, that of a parallel universe, one in which I had given birth in a different time and place, in which an unspeakable horror was in store for me and for my child.

My grandparents were Holocaust survivors. My father, too, was a survivor. He had lived through World War Two as a young child in Europe. Despite the thousands of miles and more than fifty years of time separating my family's traumatic wartime experiences from that of Ari's birth, I found myself reliving the trauma. It was deeply troubling and very strange.

When I was a young girl, we would sometimes drive up to Montreal to visit my fathers parents, whom I called Boma and Saba. The adults would put my sister and me to bed and then stay up talking about the war. But of course I was still awake, and listening, and could hear all kinds of scary things. Since I wasnt supposed to be listening, I never spoke about these late-night reminiscences. But the fear they elicited stayed deep inside me. I cant even remember any specifics of what I heard now, but I can very clearly recall lying in bed with my heart pounding, experiencing equal parts guilt for not having had to suffer as they had, and horror at what they went through.

Decades later, while I was pregnant with Ari, Danny and I watched the Holocaust movie Schindlers List. It was awful. Of course, I knew about the horrors of the Holocaust. I had read plenty of books, heard lots of stories, some even first hand. But this movie somehow clarified the degradation, the humiliation, the slavery, and the pointless sadism that the Jews endured under the Nazis. The movie struck a deep cord in me. For days afterward I couldnt sleep, images of the movie haunting my imagination, a feeling of fear permeating my being so completely that I didnt know what to do. But slowly I returned to normal, and I thought I had moved past the reaction the movie had caused me.

When Ari was born, however, those feelings came back. Even as I looked around my little house in beautiful Newburyport, part of me was living in Nazi-occupied Europe during World War Two. Profound terror shook me as I gazed at my baby boy lying in his bassinet beside me, and obsessive thoughts went through my mind what if we were being hunted? What if boots were pounding up the stairs to our room? Where would I hide? What would I do if he cried? What if I had to give him up in order to save his life?

Was it just because of what I had heard as a child that I experienced this terrible distress? Maybe. But perhaps and I mean this literally the horror of the Holocaust was actually in my DNA.

Epigenetics is a relatively new scientific field, but a fascinating one. We used to believe that our genes, which we inherit from our parents at conception, formed a permanent and unchanging blueprint of our makeup for our entire lives. In other words, you got what you got, and that was it forever. We now know that its a lot more complicated. It seems to be true that genes themselves dont change, but what is incredible is that there are countless ways that the expression of these genes is changeable. And almost everything we do, eat, or experience in life can change the way our genes are expressed.

So, it is possible that the trauma that my grandparents lived through, and that my father experienced as a child, actually changed their genes, and that these altered genes were passed on to me. If I inherited some of the trauma of the Holocaust in my very genes, maybe that explains my visceral reaction to seeing Schindlers List and other Holocaust movies, and my overwhelming anxiety when Ari was born.

My familys plight during World War Two was a story deeply rooted in my psyche. I thought a lot about it, and at the same time couldnt bear to consider it. The whole thing was too terrible, too intense. In fact, for years I tried to avoid all things Holocaust-related once I realized that seeing movies or reading books about the subject elicited anxiety, sleeplessness, and a strange kind of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in me. It was only recently that I summoned the courage to interview my relatives and to fully imagine what they went through.