2017 by Ellen G. Friedman. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America. Published by Wayne State University Press.

ISBN 978-0-8143-4413-2 (paperback); ISBN 978-0-8143-4414-9 (ebook); 978-0-8143-4439-2 (hardcover)

Library of Congress Cataloging Number: 2017953472

Wayne State University Press

Leonard N. Simons Building

4809 Woodward Avenue

Detroit, Michigan 48201-1309

Visit us online at wsupress.wayne.edu

For Sam, Simon, Joseph, Angela, and Iris

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The Seven, A Family Holocaust Story is a different story of the Holocaust, one that is lost to history and needs to be told. Most Polish Jews who survived the war did not go to concentration camps but were sentenced by Stalin to banishment in the remote prison settlements and gulags of the Soviet Union. Fewer than 10 percent of Polish Jews survived World War II, and Soviet exile was their main chance for survival.

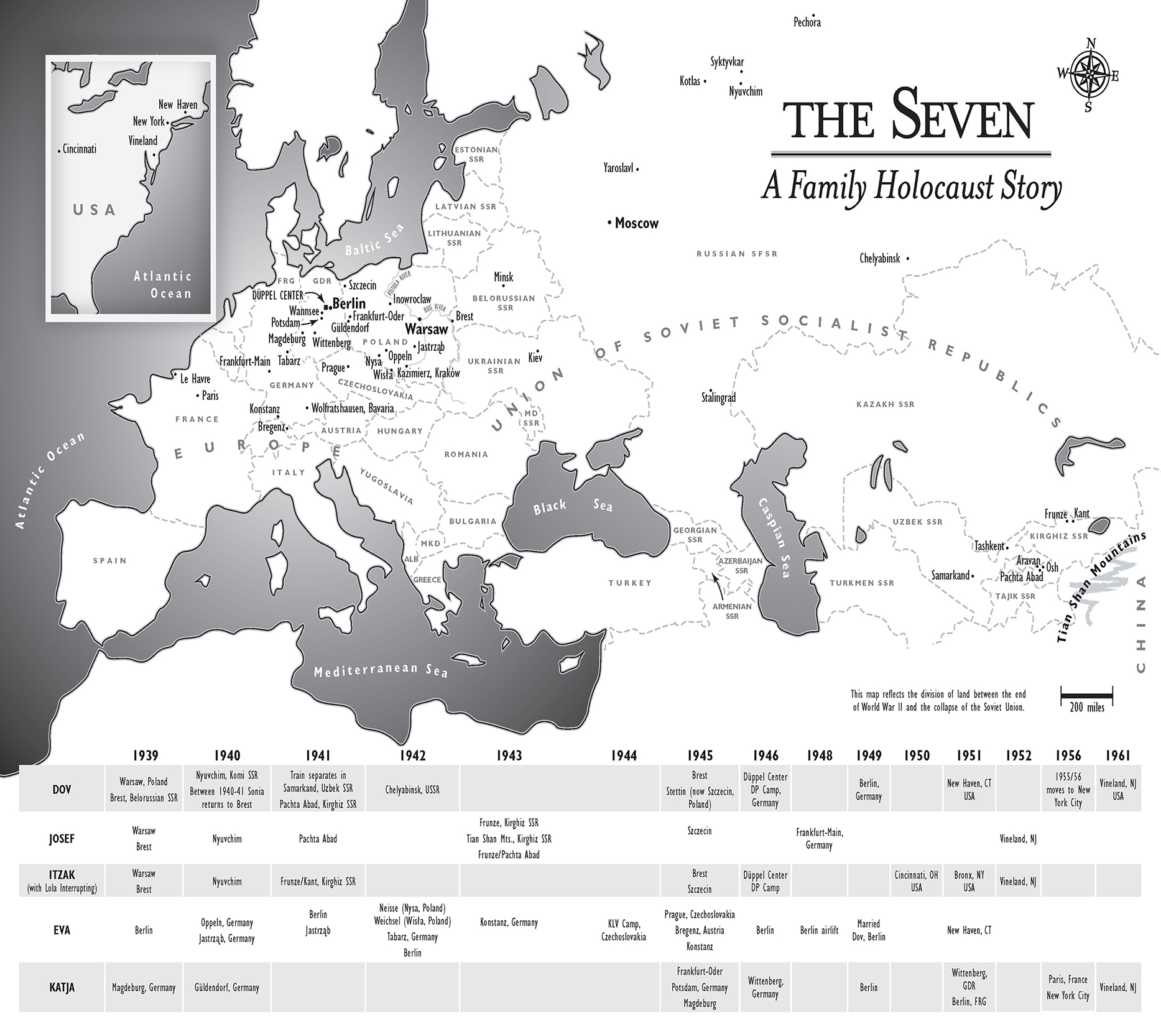

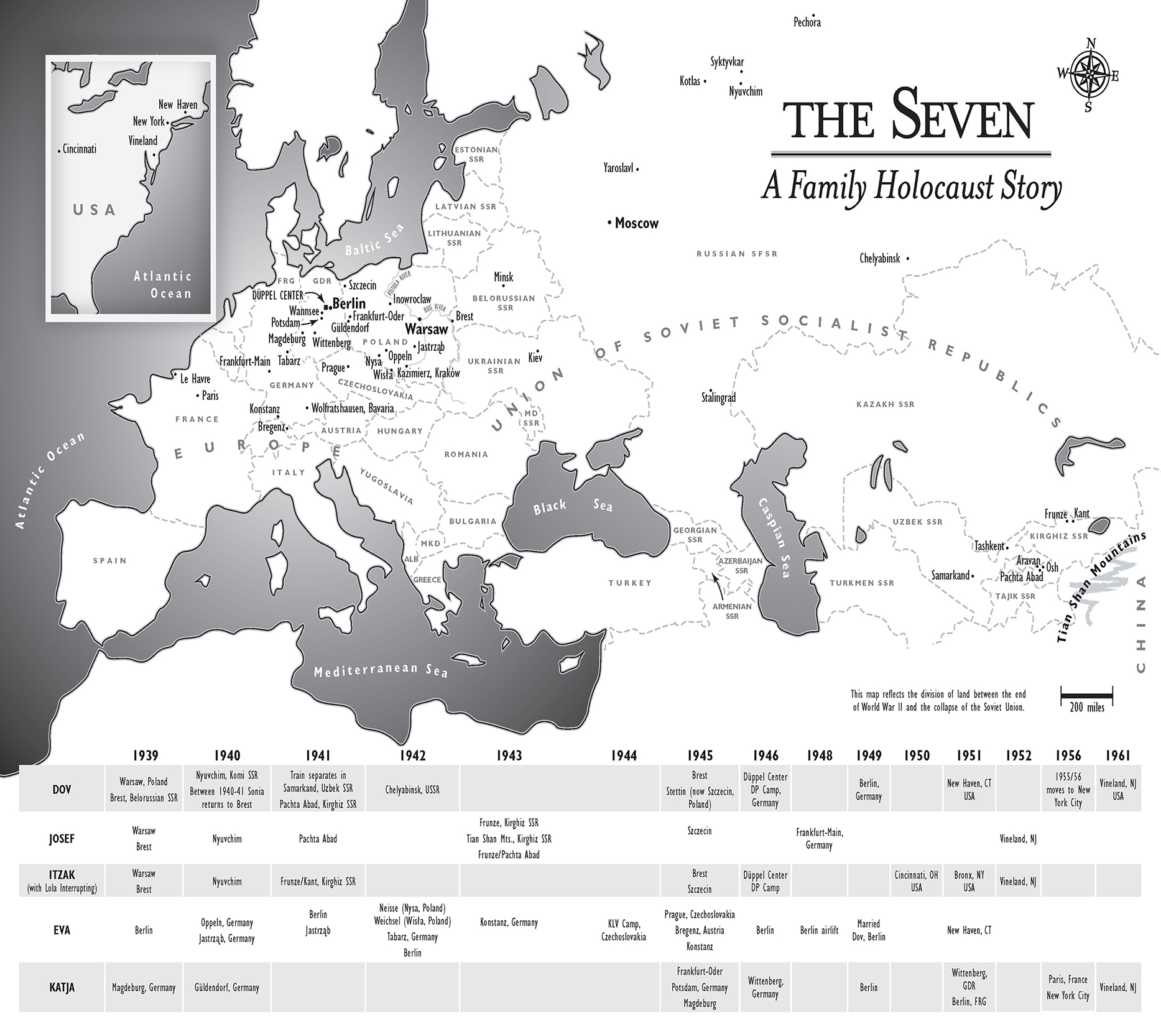

The title of this book, The Seven, is the name other refugees in the prison camps of the USSR gave to the original seven Polish Jews of this story. The Seven were from Warsaw, and I am related to six of them. Beginning in 1984, I interviewed those of the Seven who were still alive, as well as others who had entered their sphere and became part of a more metaphorical, extended Seven. Set side-by-side and in juxtaposition to one another, their voices tell a new Holocaust storyone that resonates with the experiences of todays exiles and refugees.

After Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Polish government in exile made a deal with Stalin to liberate Polish citizens from the prison settlements in the USSR. Many Polish Jews went south to Soviet Asia, looking for better living conditions than they had in the cold northern territories of their banishment. Thats where I was bornin Kyrgyzstan, within sight of the Tian Shan Mountains of China.

I have been asked about my methodology. It is not one I recommend. It was an organic process that began without a plan. In 1978, when the television series Holocaust aired, American attention finally turned to the horrors of Nazism. I always knew I was born in a small Kyrgyz hamlet outside of Kant, a village near Frunze (now Bishkek), to Polish-Jewish parents on the run from Hitler. But my family did not describe themselves as Holocaust survivors. American culture, indeed everyone and everythingbooks, news media, film, and televisiondefined Holocaust survivors as people who had come out of death and concentration camps, people with numbers tattooed on their arms. Although I was busy raising a family and pursuing my career as a professor of English, occupied with courses and literary scholarship, it was clear to me that the time had come to record the stories of my family.

They allowed me to record them when I told them the audio tapes were for a book I wanted to write about them, a vague notion at first that gained ground and clarity over time, much time. As this material began to take hold of me, I tried to put their experiences into fiction and with my husband to write a novel about them, but good intentions could not glue together our two different imaginations, and the collaboration fizzled outthough the marriage held. With the new millennium and the deaths of some of the Seven, I began this memoir in earnest. I re-interviewed the ones who were still alive and recorded spouses for the first time, as well as some of their children. I hired undergraduate and graduate students to transcribe the dozens of audio tapes that held their stories. After the transcriptions were finished, my plan was to correct them, since the many place names and multiple languages involved were foreign to my students. I also applied for a travel grant to put my feet on the landscapes where the stories had taken place. The Soviets blocked access to some of the places I wished to see, such as Nyuvchim in Komi, to which the Seven were banished in 1940, and Kant in Kyrgyzstan, but I got close enough to these geographies to get a sense of them. In the meantime, I read as much as I could about the history of those years and I pored over maps. In the end, I just began to write because the work of correcting the transcriptions, it seemed, would last beyond my lifespan.

Sometime near the beginning, a voice in my head took over the writing and I finished a draft. Writing a book takes a long time, at least this book did, and as I wrote, memories, news stories, things I read and felt, and my daily life worked their way into the text. Writers have said that at a certain serendipitous moment in a book, the whole world seems to collaborate in its composition. Everything seems relevant and begs to be included. My manicurist, rock and roll, Esperanto, Michel Foucault, whose work I teach, President Obama, Bob Dylan, and Arthur Murrayall of them slipped into my manuscript. Thats how this book acquired its unconventional form, a pastiche of past and present, of them and me and a Holocaust history that has finally found the opportunity to make itself known.

This memoir is personal and if intent counts, universal. To preserve anonymity and privacy, I have changed names, some identifying characteristics and details, as well as occupations and places of residence. I have compressed and edited the interviews to fill logical gaps and reflect historical circumstances, and for purposes of the narrative, I have added and emended material. Although based on interviews, this memoir is my account, my history, my version of their stories. Each of the people described in this book, if they had been so inclined, likely would have portrayed themselves differently than I have portrayed them. I have kept the names of my parents, Itzak and Lola, as a way to memorialize themalthough they would not have approved of how I present them, as you will see.

Who and Where

They were seven Polish Jews from Warsaw and it was 1939. I heard their stories when I was already married and a mother. I dont know if they told them before then; I only know thats when I began to pay attention. It must have been around the time of the American awakening to the Holocaust in the late 1970s and 1980s, with TV specials and movies suddenly giving status to their European accents. This attention encouraged my father and his two brothers to talk more about what happened to them, even though theirs wasnt a Holocaust experience of the first order. The stories captivating Americans were about concentration camps and gas chambers and death. My family stories, about how they outwitted their circumstances and survived, were the kind that did not count as about the Holocaust, until now.

This, then, is a Holocaust story plucked from the least known yet most common of the stories of Polish Jews who survived World War II. Most Polish Jews still alive after the Holocaust spent the war in the Soviet Union. So its a story of exile. And its also a story of familymy family. Most of the people you will get to know best are survivors who lost almost everything important they hadparents, brothers, sisters, and one would say homeland, but it seems Jews do not have a homeland, and even Israel, the default homeland, has its problems. Once the Seven escaped the Germans in Warsaw, they did not return, even after the war, but kept going, out of the Soviet Union, out of Poland, out of Europe.

For sure, death was there, too. Of these seven Polish Jews who left Warsaw for exile, six lived out a natural life span. But another sixty, according to the statistics, 90 percentparents, grandparents, sisters, brothers, aunts, uncles, cousins, nieces, nephews, an entire family network, almost the whole of the

Next page