For my mother, Anne Weiskopf Steinman, who believed we must always inquire.

Oh sun, moon, stars, our other relatives peering at us from the inside of gods house walk with

us as we climb into the next century naked but for the

stories we have of each other. Keep us

from giving up in this land of nightmares which is

also the land of miracles.

JOY HARJO, FROM RECONCILIATIONA PRAYER

INTRODUCTION

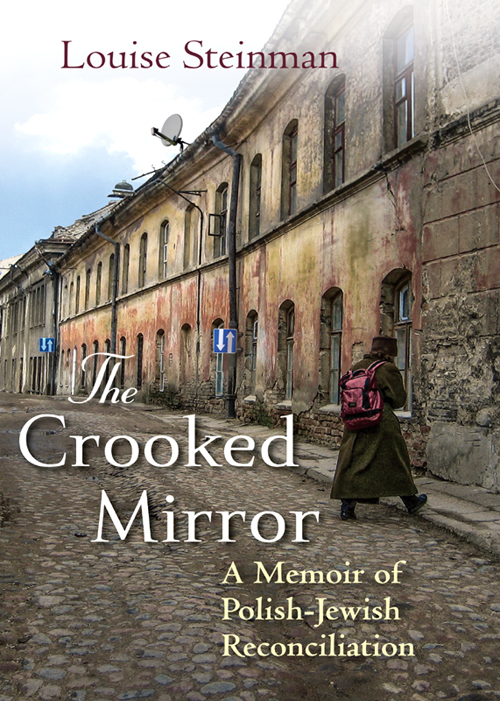

The Country in My Head

Cinders drifted over the heads of family and friendsfire season in Southern California. The rabbi sang so ecstatically from the Song of Songs, some of the wedding guests wondered if he was on acid.

It was 1988, my second marriage, my husbands third. In the past, neither of us had considered a religious ceremony. But all four of our parents were then alive, and we knew it would give them sweet pleasure to see us married under the chupa, the traditional Jewish wedding canopy.

When we began planning, knowing our ambivalence about tradition, a friend directed us to Don Singer, the Zen Rabbi of Malibu.

Don met us at the door of his house with a parrot on his shoulder. He was white-haired, handsome; laugh lines radiated from bright blue eyes. We warmed immediately to his unorthodoxy, his innate joie de vivre.

Don Singer really was a Zen rabbi. His understanding of Buddhism harmonized with his embrace of Hasidic wisdom. His congregation gathered for Shabbat and High Holy Day services in the garden behind the Los Angeles Zen Center, located in one of the citys poorest neighborhoods. On Rosh Hashanah, blasts from the traditional rams horn (shofar) mingled with catchy tunes from an ice cream truck and the beat of salsa from boom boxes. In Rabbi Singers eclectic, roaming congregation, I found a contemplative home for my unaffiliated and long-estranged Judaism.

Sometimes at his services, Don spoke about his experiences in Poland. Every winter for five years in a row, Rabbi Singer had served as the principal rabbi for the Bearing Witness Retreat at Auschwitz-Birkenau, an interfaith gathering organized by the Zen Peacemaker Order.

When Don was a teenager in the fifties, his artist father took him to visit the death camp at Dachau. It is the source of what I am today as a rabbi, he confided. His early experiences led him to explore the authentic roots of Judaism and what he considers its most radical commandment: You shall love the stranger as yourself, for you were a stranger in Egypt, and you know the heart of the stranger.

In one of his Friday night talks, Rabbi Singer mentioned Polish-Jewish reconciliation. He felt a responsibility to bring Poles and Jews together. I couldnt imagine why.

When I went to Poland for the first time and met some Polish people, I felt a startling affinity, he said. He took pleasure in the thought that his grandmother came from there. The Jews were part of Polands body and soul, he said. I felt somehow we knew the Poles, that we understood them. I realized they received a bum rap.

I fumed... a bum rap? Like so many others, I erroneously assumed the Nazis located their extermination camps in Poland because they expected the Poles would be willing collaborators. Id heard that Poles murdered Jews even after the war ended. The infamous July 1946 pogrom in the town of Kielce, Poland, against Jews whod returned from the camps, caused mass panic among those Polish Jews whod survived the war. Forty Jews were murdered in Kielce, despite a large presence of police and army militia. The violence raged on for more than five hours.

The Kielce pogrom convinced many of those Polish Jews whod survived the war to flee the country. The incident loomed ominously over Diaspora Jews images of postwar Poland. When I first learned of the Kielce pogrom, in my teens, its logic eluded me. Why would people persecuterather than protectsurvivors who made it back to their homes?

Polish-Jewish reconciliation had the ring of a bad joke, like the premise of Philip Roths novel Operation Shylock, in which Israeli Jews emigrate back to Poland in a reverse Diaspora. For my familyas for so many other American Jews of Polish descentPoland was a black hole, a gnawing void.

I took note that many, if not most, of my Jewish friends had family ties to Poland. An estimated 80 percent of American Jews are of Polish Jewish descent. There was scant generosity in their feelings about Poland; always dependable heat. Most harbored more bitterness toward Poland than they did toward Germany, a fact that I never questioned as odd, misplaced.

The Jews may have once been part of Polands body and soul, but theyd been excised, cast out.

My own mother could barely utter the word Poland. Her grief at the loss of unnamed family in Poland during the Holocaust rendered painful even the sound of where it happened. It was a given that Poland was a country full of people who hated Jews, who allowed and perhaps even abetted an unspeakable genocide on their soil. Bitterness calcified, and in my home and among my generation of comfortable suburban Los Angeles Jewish kids, the very idea of Poland resonated anguish and betrayal in a way it did not for other Americans.

MY MOTHERS PARENTS EMIGRATED from Poland to the United States in 1906. Back beyond that, silence. Even as a child and without knowing why, the absence of family history on my maternal side was a gap, an ache.

My fathers mother, my Russian grandmother, was a gifted storyteller. Rebecca (Becky) Steinman read Hebrew and spoke Yiddish, Russian, Ukrainian, Polish, and heavily accented English.

Beckys stories of flight and migration fascinated me. It was a Polish farmer, she said, whoin 1921 with a civil war ragingsmuggled my grandmother with her two children out of Ukraine and into Poland on his horse-drawn cart covered with a bed of straw. In recompense, she gave the Polish farmer the family samovar.

I loved watching my grandmother light Friday night candleseyes closed, chanting singsong Hebrew and gesturing both arms in wide circles toward her heart to embrace the light. She told tales of dream peddlers, traveling Jewish merchants who passed through her village selling pots and pans, zippers, combs, ribbons, and special books explaining the meaning of all ones dreams. She advised me to share my dreams with only three smart people.

But on my mothers side, no one talked. Did they not know about their Polish past? Had it been forgotten so quickly?

I knew that my mothers mother, Sarah Konarska Weiskopf, came from a place in Poland called Czestochowa, and that my mothers father, Louis Weiskopf, came from a town nearby called Radomsk. The word tickled me as a child. Ra-dumpsk! I imagined Radomsk as an impoverished backwater, like Dogpatch in those Lil Abner cartoons we read on Sunday morning.

I remembered Grandma Sarah as an exhausted old woman who lived in a tiny apartment on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn, tied her wisps of white hair into a bun secured with bobby pins, and, to my eternal fascination, hid rolls of dollar bills in her oven. Grandpa Louis died before I was born. Four of my generationincluding mewere his namesakes.

Growing up in 1950s Los Angeles, in an orderly grid of postwar stucco houses, it wasnt as if I was surrounded by kids who could recite their ancestors back to the Mayflower. Had I queried my playmates, I would have learned that almost all of them had gaping holes in their family histories. My father, like many others on our block, had returned from the warin his case, combat in the Pacific. The priorities were building economic security, starting families, launching businesses. My dads new pharmacy in Culver City was open 9:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m., and he was always there. My mother had three young children to supervise, including my sister who had polio. Being severed from ones family past wasnt supposed to matter.

Next page