Copyright 2001 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gross, Jan Tomasz.

[Sasiedzi. English]

Neighbors : the destruction of the Jewish community in Jedwabne, Poland / Jan T. Gross.

p. cm.

Originally published: Sasiedzi: historia zagady zydowskiego miasteczka.

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

ISBN 0-691-08667-2 (alk. paper)

1. JewsPolandJedwabneHistory. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)PolandJedwabne. 3. Jedwabne (Poland)Ethnic relations. I. Title: Destruction of the Jewish community in Jedwabne. II. Title.

DS135.P62 J444 2001

940.53180943843dc21 00-051685

This book has been composed in Janson

Printed on acid-free paper.

www.pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history.

Abraham Lincoln,

Annual Message to Congress

DECEMBER 1, 1862

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

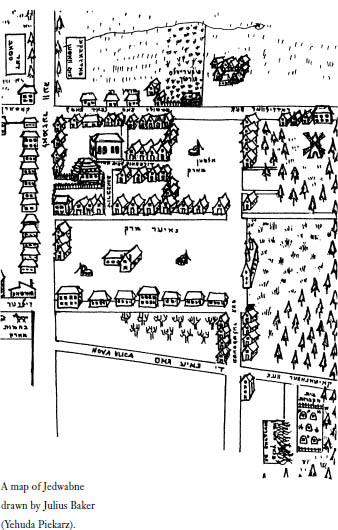

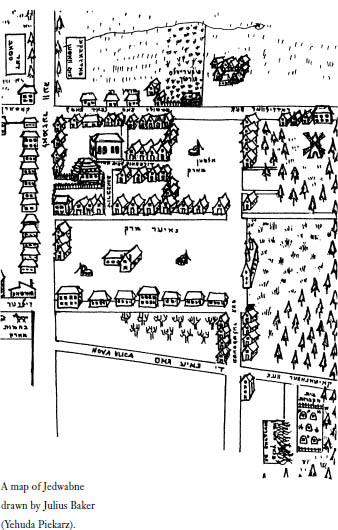

This book could not have been written without the assistance of Rabbi Jacob Baker in New York and Professor Andrzej Paczkowski in Warsaw. I gratefully acknowledge Rabbi Bakers permission to reproduce the photographs included here. I am grateful to attorney Ty Rogers for putting me in touch with many former Jedwabne residents and their descendants.

I owe a debt of gratitude to several people who helped me with the writing of this book. For the most part I thank them in the endnotes. Here, I would like to express my special thanks to Stephanie Steiker for her editorial assistance and unfailing emotional support, as well as to Valerie Steiker and Magda Gross for many useful editorial suggestions. I am deeply grateful to Lauren Lepow for copy-editing the final draft of the manuscript with consummate skill.

I wish to thank the Remarque Institute of New York University for appointing me a faculty fellow in spring 2000. This provided me with ample time to complete the manuscript. The Institutes director, Tony Judt, as well as two readers for Princeton University Press, Mark Mazower and Antony Polonsky, offered useful comments for which I am also grateful. Last but not least, I want to thank the history editor at Princeton University Press, Brigitta van Rheinberg, who watched over the manuscript of this book with skill and enthusiasm from the beginning.

I dedicate Neighbors to the memory of Szmul Wasersztajn.

NEW YORK

JUNE 2000

INTRODUCTION

Twentieth-century Europe has been shaped decisively by the actions of two men. It is to Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin that we owe totalitarianismif not its invention, then certainly its most determined implementation. The loss of life for which they are jointly responsible is truly staggering. Yet it is not what happened but what has been prevented from ever taking place that gives a truer measure of totalitarianisms destructiveness: the sum of unwritten books, as one author put it. In fact, the sum of thoughts unthought, of unfelt feelings, of works never accomplished, of lives unlived to their natural end.

Not only the goals but also the methods of totalitarian politics crippled societies where they were deployed, and among the most gripping was the institutionalization of resentment. People subject to Stalins or Hitlers rule were repeatedly set against each other and encouraged to act on the basest instincts of mutual dislike. Every conceivable cleavage in society was eventually exploited, every antagonism exacerbated. At one time or another city was set against the countryside, workers against peasants, middle peasants against poor peasants, children against their parents, young against old, and ethnic groups against each other. Secret police encouraged, and thrived on, denunciations: divide et impera writ large. In addition, as social mobilization and mass participation in state-sponsored institutions and rituals were required, people became, to varying degrees, complicitous in their own subjugation.

Totalitarian rulers also imposed a novel pattern of occupation in the territories they conquered. As a result, wrote Hannah Arendt, they who were the Nazis first accomplices and their best aides truly did not know what they were doing nor with whom they were A comprehensive answer to this question would have to be sought in multiple studies of German regimes of occupation.

After the fact, public opinion all over Europe recoiled in disgust at virtually any form of engagement with the Nazis (in an arguably somewhat self-serving and not always sincere reaction). It is nearly impossible to calculate the total number of persons targeted by postwar retribution, but, even by the most conservative estimates, they numbered several million, that is 2 or 3 percent of the population formerly under German occupation, writes

While the experience of the Second World War has to a large extent shaped the political makeup and destinies of all European societies in the second half of the twentieth century, Poland has been singularly affected. It was over the territory of the pre-1939 Polish state that Hitler and Stalin first joined in a common effort (their pact of nonaggression signed in August 1939 included a secret clause dividing the country in half) and then fought a bitter war until one of them was eventually destroyed. As a result Poland suffered a demographic catastrophe without precedent; close to 20 percent of its population died of war-related but during that time it must have felt more like a stomping ground of the devil.

The centerpiece of the story I am about to present in this little volume falls, to my mind, utterly out of scale: one day, in July 1941, half of the population of a small East European town murdered the other halfsome 1,600 men, women, and children. Consequently, in what follows, I will discuss the Jedwabne murders in the context of numerous themes invoked by the phrase Polish-Jewish relations during the Second World War.

First and foremost I consider this volume a challenge to standard historiography of the or scum, who blackmailed Jews, and the heroes who lent them a helping handwere involved with the Jews.

This is not the place to argue in detail why such views are untenable. Perhaps it is not even necessary to dwell at length on this matter. After all, how can the wiping out of one-third of its urban population be anything other than a central issue of Polands modern history? In any case, one certainly needs no great methodological sophistication to grasp instantly that when the Polish half of a towns population murders its Jewish half, we have on our hands an event patently invalidating the view that these two ethnic groups histories are disengaged.

The second point that readers of this volume must keep in mind is that Polish-Jewish relations during the war are conceived in a standard analysis as mediated by outside forcesthe Nazis and the Soviets. This, of course, is correct as far as it goes. The Nazis and the Soviets were indeed calling the shots in the Polish territories they occupied during the war. But one should not deny the reality of autonomous dynamics in the relationships between Poles and Jews within the constraints imposed by the occupiers. There were things people could have done at the time and refrained from doing; and there were things they did not have to do but nevertheless did. Accordingly, I will be particularly careful to identify who did what in the town of Jedwabne on July 10, 1941, and at whose behest.

Next page