KENNETH GROSS teaches English at the University of Rochester and is the author, most recently, of Shylock Is Shakespeare (2006), also published by the University of Chicago Press.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2011 by Kenneth Gross

All rights reserved. Published 2011.

Printed in the United States of America

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-30958-3 (cloth)

ISBN-10: 0-226-30958-4 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-30960-6 (e-book)

An earlier version of parts of the prologue and parts of was included in Love among the Puppets, Raritan: A Quarterly Review 17, no. 1 (1997): 6782.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gross, Kenneth.

Puppet : an essay on uncanny life / Kenneth Gross.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-30958-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-226-30958-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Puppets in literature. 2. Puppet theaterHistory and criticism. I. Title.

PN1972.G766 2011

791.53dc2

2010052565

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

PUPPET

An Essay on Uncanny Life

KENNETH GROSS

PUPPET

FOR LIZA

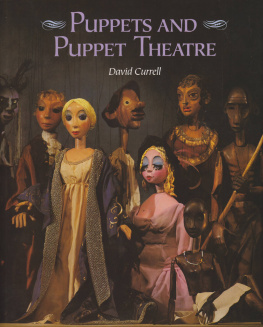

ILLUSTRATIONS

PROLOGUE

The Madness of Puppets

WHAT IS THIS thing that I recognize, that seems to know me, when I come upon it on a street corner, in a park, or in the shadows of a theater, moving up on that small stage? What is this creature that burrows out of shadows, into the light, a remnant of something, hardheaded, often squeaking and ugly, moving with such odd, unpredictable motion, or just lying still, folded up on itself, a little warm, patiently gathering strength for some new movement? I wonder about the world in which this creature lives. I wonder more what it knows about our world.

The madness of the puppet. It lies along a line or spectrum of things. It might be a very ordinary form of madness. The madness lies in the hidden movements of the hand, the curious impulse and skill by which a persons hand can make itself into the animating impulse, the intelligence or soul, of an inanimate objectit is an extension of that more basic wonder by which we can let this one part of our body become a separate, articulate whole, capable of surprising its owner with its movements, the stories it tells. I call it madness, but it is perhaps better called an ecstasy. It lies in the hands power and pleasure in giving itself over to the demands of the object, our curious will to make the object into an actor, something capable of gesture and voice. What strikes me here is the need for a made thing to tell a story, to become a vehicle for a voice, an impulse of charactersomething very old, and very early. The thing acquires a life.

The madness will also have something to do with the made puppet itself, so often a crude and disproportioned thing, with its staring eye and leering teeth, its tiny hands, the impossible red or blue of its face, barely human in form, like a monster or mistake, a fetus or a corpse. The madness lies in the wild actions that come to belong to that object, that seem, indeed, proper to it: its rhythmic dance, its talent for trickery, its speed of attack, its delicate way with a stick or bit of paper, its skill in disappearance and reappearance. Characters human and inhuman, close to objects. In this theater, what looks like a wooden block or ball, a bundle of rags, a thin silhouette of perforated leather, assumes a voice and personality. In the right hands, a mere strip of paper moved by a string, yielded to accidents of air, can do it. All acquire intentions, what looks like will, even if this belongs to things we think can have no will. All acquire different souls and spirits, all have different stories to tell. They are able to enter into our histories, and reenact our histories.

Then there is the intense, often mysterious quality of the audiences fascination with these wooden actors, and with the seen and unseen face of the puppet show. Fear there can be, also an unsettling delight, the trace of the intimacy we can achieve with alien things. The playwright Paul Claudel, in 1926, described a puppet show he saw in Japan, though it sounds as much like a performance of the French clown puppet Guignol: And behindits so amusing to keep well hidden and make someone come to life; to create that little doll that goes in at the eyes of every spectator to strut and posture in his mind! In all those rows of motionless people only this little goblin moves, like the wild elfish soul of all of them. They gaze at him like children, and he sparkles like a little firecracker! There is something in the puppet that ties its dramatic life more to the shapes of dreams and fantasy, the poetry of the unconscious, than to any realistic drama of human life. That is part of its uncanniness, that its motions and shapes have the look of things we often turn away from or put off or bury. It picks out our madness, or what we fear is our madness. It creates an audience tied together by childlike if not childish things. It is amazing, the scream of children trying to warn Punch that there is a crocodile hiding behind him, a creature who disappears instantly below stage every time that Punch turns around to catch a glimpse of him. Keeping watch on the audience that watches a puppet show is often part of the fascination. Franois Truffauts 1959 film The 400 Blows, as an interlude in its picture of wounded childhood, contains a stunning few minutes of footage showing the faces of an audience of young French children watching a puppet show of Red Riding Hood, each face distinct yet part of a unified sea of wonder. They are wildly absorbed by what they see, crying out warnings (Le loup! Le loup!), elated even by their fear for the puppet heroine set upon by a puppet wolf.

Puppet theater has its ambivalences. It can produce less touching forms of fright, a sense of mere creepiness, not to mention a sense of its being something trivial or contemptible. One of Goethes Venetian Epigrams (1796) suggests a more violent response: I fell in love as a boy with a puppet show; / It attracted me for a long time until I destroyed it. That too is part of the madness I would describe. It is not quite the same as the act of putting away childish things. Theres something so loaded, so odd about the very word puppet in English that it cant help but evoke divided responses in those who hear it, even those who are themselves involved in the art. The word derives from the Latin pupa, for little girl or doll, a word still used in entomology to describe the mysterious, more passive middle stage of an insects metamorphosis, as the larva is covered in a chrysalis, and awaits reemergence as a winged thing. Such an analogy has some resonance, and yet the word puppet, itself a diminutive, still sounds a little like a childs word, as well as being a word for a child. Used metaphorically, it gets applied to a thing or person both insignificant and subjected to the power of othersnot a word people will readily apply to themselves. In Shakespeares time, puppetsometimes poppetmight be an endearment, but also a term used to derogate both actors and servile politicians, or to mark a woman as a painted seductress, even a prostitute. Fie, fie, you counterfeit, you puppet, you! cries Helena to Hermia in

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).