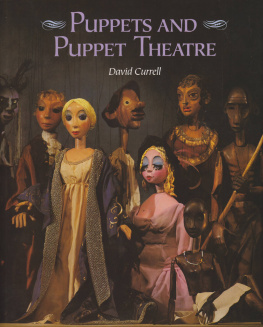

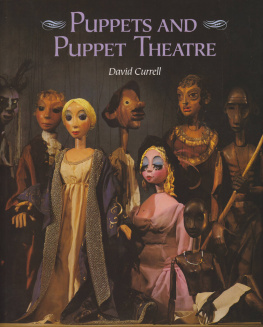

P UPPETS AND

P UPPET T HEATRE

David Currell

First published in 1999 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

David Currell 1999

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 790 8

To Emily Aya and Alexander Emre, my children, who love puppet theatre.

Photo Credits

Courtesy John M. Blundall, Puppet Theatre Consultant, The Scottish Mask and Puppet Theatre Centre, Glasgow: .

Acknowledgements

P uppeteers world-wide are generous in sharing their knowledge, skills and experience, and I have been extremely fortunate to benefit from this generosity in the preparation of Puppets and Puppet Theatre.

For information on their approaches to puppet making and performing, as well as for photographs, I am indebted to John Blundall, Ray DaSilva, Mary Edwards, Geoff Felix, Christopher Leith, Ian Purves and Lyndie Wright. Technical information on lighting and sound has been received from Sue Davies and Bill Richards of Strand Lighting Limited, Claire House of Zero 88 Lighting Limited, and Mark Piatkowski of Coomber Electronic Equipment Limited. Others who have contributed photographs are listed separately.

My very sincere thanks are due to David Rose, a friend, colleague, and photographer, who has been extremely generous with his time and expertise, and has made it possible to include so many colourful and informative photographs.

I am grateful also to Loretta Howells (Director), Allyson Kirk and Glen Alexander of the Puppet Centre Trust, London, who have provided reference resources, technical information and photographs, and made available the Trusts extensive collections for photography.

The late Barry Smith, Director of the Theatre of Puppets and Ray DaSilva, Co-Director of the DaSilva Puppet Company, shared their individual approaches to puppet performance for a previous book, which is embedded also in the present work. I therefore acknowledge with gratitude the major contributions made to the performance chapter by each of these puppet masters.

Finally, I am extremely grateful to the team at The Crowood Press, who have been enthusiastic and supportive, and helped to make the book a pleasure to write.

A marionette carved by John Wright, The Little Angel Theatre, London

1 An Introduction to Puppet Theatre

PUPPET THEATRE HERITAGE

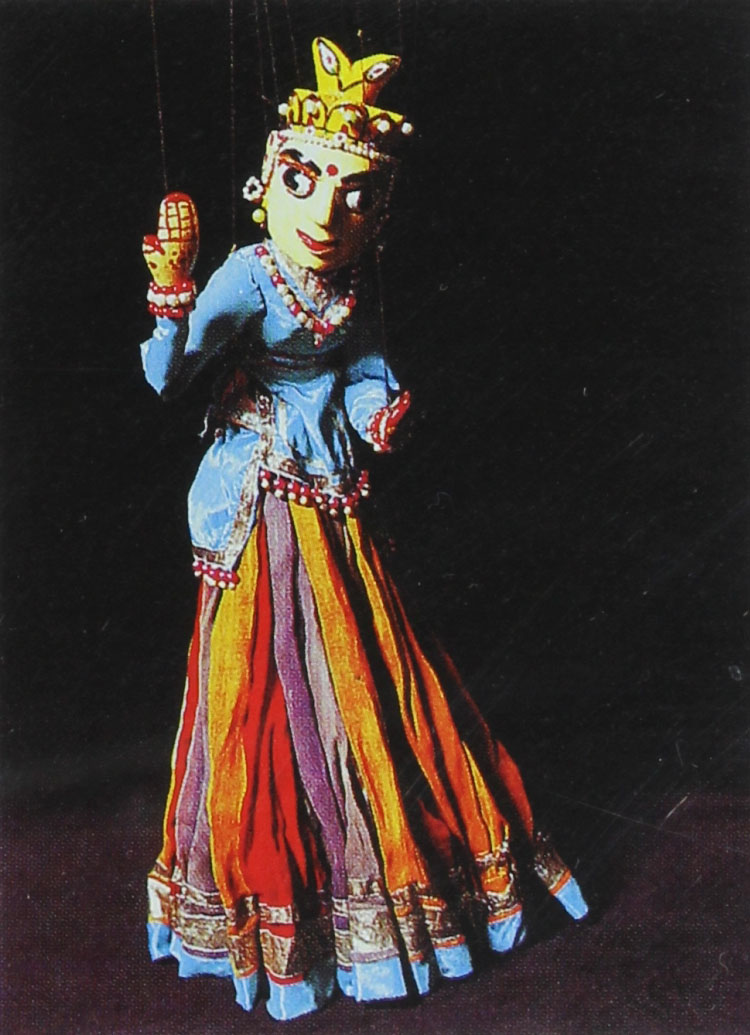

P uppetry and puppet theatre have a long and fascinating heritage. The origins of this visual and dramatic art are thought to lie mainly in the East, although exactly when or where it originated is not known. It may have been practised in India 4000 years ago: impersonation was forbidden by religious taboo and the leading player in Sanskrit plays is termed sutradhara (the holder of strings), so it is likely that puppets existed before human actors.

Fig 1 Javanese wayang golek rod puppets

In China, marionettes were in use by the eighth century AD and shadow puppets date back well over 1000 years. The Burmese puppet theatre had a significant influence on the development of the human dance drama, and a dancers skill is still judged on his or her ability to re-create the movements of a marionette. And Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1725), Japans finest dramatist, wrote not for human theatre, but for the Bunraku puppets (see once overshadowed the Kabuki in popularity.

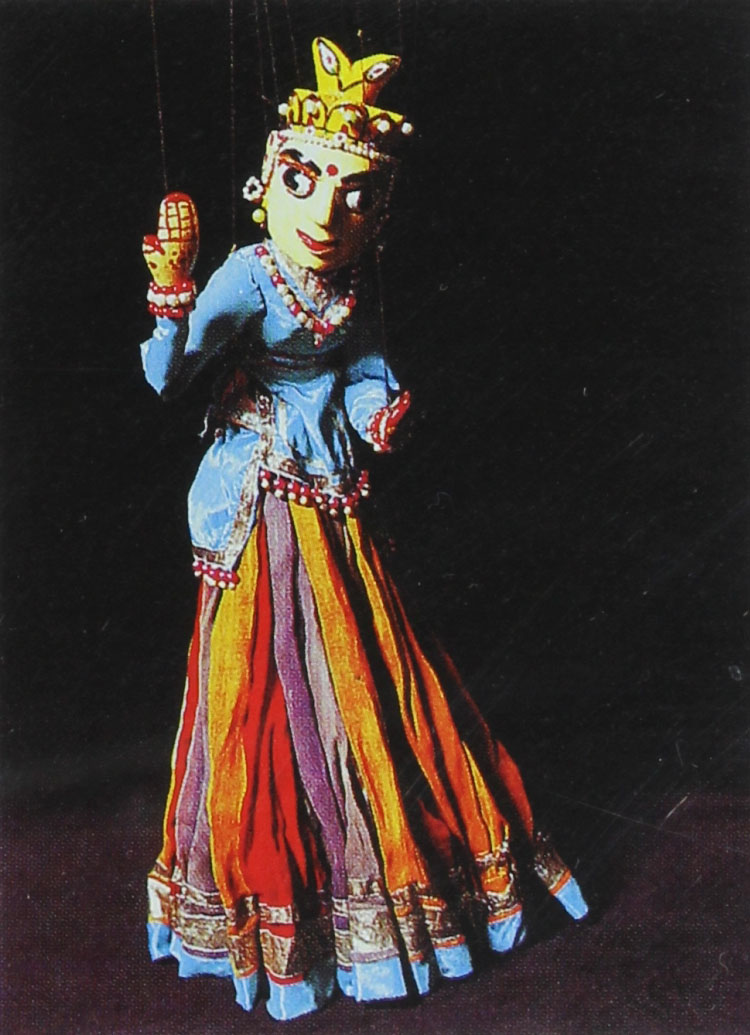

Fig 2 An Indian marionette from the Rajasthan region

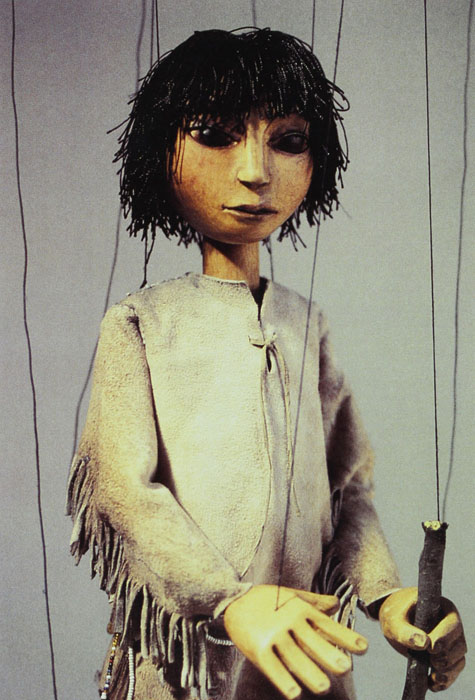

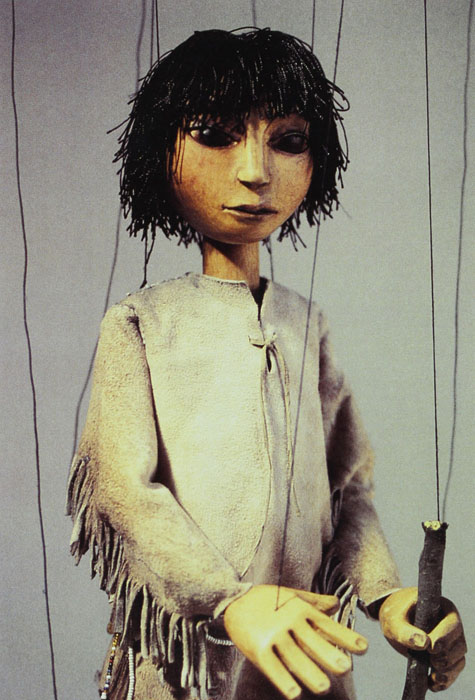

Fig 3 A traditional carved Burmese marionette

In Europe, the puppet drama flourished in the early Mediterranean civilizations and under Roman rule. The Greeks may have used puppets as early as 800 BC, and puppet theatre was a common entertainment probably with marionettes and glove puppets in Greece and Rome by 400 BC, according to the writings of the time. In the Middle Ages, puppets were widely used to enact the scriptures until they were banned by the Council of Trent. Since the Renaissance, puppetry in Europe has continued as an unbroken tradition.

Sicilian puppets knights one metre (three feet) high, wearing beaten armour and operated from above with rods (see ) have performed the story of Orlando Furioso since the sixteenth century, but this type of puppet was, in fact, in use as long ago as Roman times. In Germany, puppets have performed The History of Doctor Faustus since 1587, and in France marionette operas became so popular that in 1720 the live opera attempted to have them restricted by law. The eighteenth-century French Ombres Chinoises shadow puppets were not only a fairground entertainment but were popular among artists and in the fashionable world.

In England, puppets were certainly known by the fourteenth century and, during the Civil War, when theatres were closed, puppet theatre enjoyed a period of unsurpassed popularity. By the early eighteenth century it was a fashionable entertainment for the wealthy, and in the late nineteenth century Englands marionette troupes, considered to be the best in the world, toured the globe with their elaborate productions.

The ubiquitous Mr Punch originated in Italy. A puppet version of Pulcinella, a buffoon in the Italian Commedia dell Arte, was carried throughout Europe by the wandering showmen and a similar character including Petruschka (Russia), Pickle Herring, later Jan Klaasen (Holland), and Polichinelle (France) became established in many countries. The French version was introduced to England in 1660 with the return of Charles II; it became Punchinello, soon shortened to Punch, and enjoyed such popularity that he began to be included in all manner of plays. By 1825, Punch was at the height of his popularity, and the story in which he played had taken on its standard basic form.

In the nineteenth century the puppet show was taken to America by emigrants from many European countries, and their various national traditions laid the foundations for the great variety of styles found there today.

Eastern Europe had early traditions of travelling puppet-showmen but, with a few exceptions, puppetry did not develop significantly there until the twentieth century. However, it then progressed at an impressive rate.

The twentieth century has brought new materials and techniques to puppet theatre, and has seen a revival of interest in the art through television and film, as well as a renewed emphasis on the quality of live performances. Official recognition of puppetry as a performance art has now been achieved.

THE NATURE OF THE PUPPET

The survival of puppet theatre over some 4000 years owes a great deal to mans fascination with the inanimate object animated in a dramatic manner, and to the very special way in which puppet theatre involves its audience. Through the merest hint or suggestion in a movement perhaps just a tilt of the head the spectator is invited to invest the puppet with emotion and movement, and to see it breathe.

Next page