Gross - The last Jews in Berlin

Here you can read online Gross - The last Jews in Berlin full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Berlin (Allemagne), year: 2015, publisher: Open Road Media, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

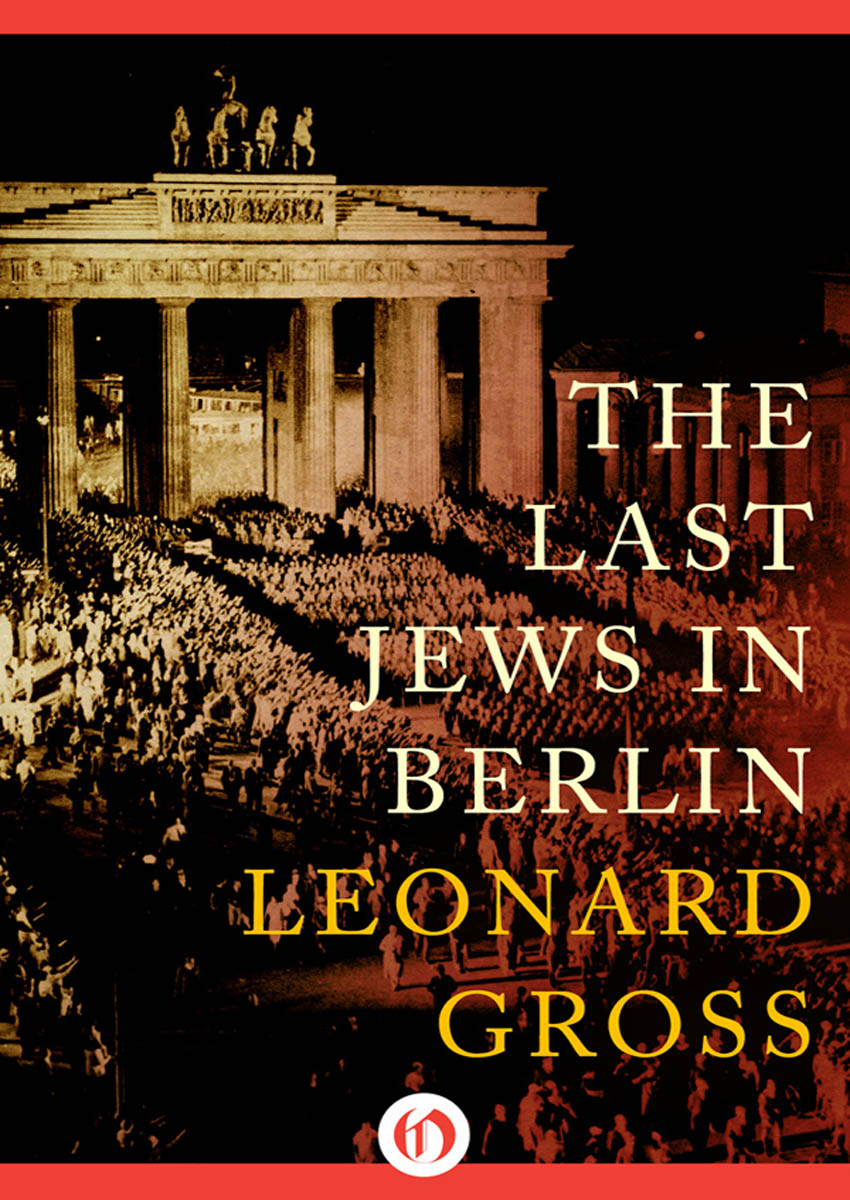

- Book:The last Jews in Berlin

- Author:

- Publisher:Open Road Media

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- City:Berlin (Allemagne)

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The last Jews in Berlin: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The last Jews in Berlin" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The last Jews in Berlin — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The last Jews in Berlin" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Last Jews in Berlin

Leonard Gross

In memory of my father,

Benjamin Gross

AUTHORS NOTE

T HE INTERVIEWS on which much of this book is based were actually begun a decade before I became involved. In 1967 Eric Lasher, an editor and writer, journeyed to Berlin in the hope of finding Jews who had spent the entire war in that city, for much of that time hiding from the Nazis. From reports he had read, Lasher knew such people existed. But their story had never been fully told.

Lasher advertised in a Jewish community newspaper published in Berlin. Eighteen men and women responded. He interviewed all of them, as well as other survivors to whom their stories led him. All the interviews were extensive, and all of them were taped. But Lasher was unable to continue work on the book because of personal reasons, one being that he found the material so upsetting he had developed a stammer. He reluctantly but realistically dropped the project and put the transcripts of his interviews, as well as many files of allied material, in storage.

In the early 1970s Lasher and I both moved to California with our families and settled a few miles apart on the west side of Los Angeles. We had known of one another professionally; now, as our friendship ripened, he told me of the project and of his great disappointment that it had never been completed. I wondered if I might not take on the project, and, after reading through the transcripts, volunteered to do so.

The transcripts raised more questions than they answered, but theyand corollary material I subsequently acquiredproved beyond doubt that several thousand Jews in Berlin alone had undertaken to save themselves from extinction by the Nazis.

My task, as I saw it, was to choose several representative stories from Lashers material and develop them in great detail.

In the summer of 1978 my wife, Jacquelyn, and I flew to Berlin to try to make contact with the survivors. I was filled with foreboding. Would they still be alive, and could they be located? They had told their stories once before; would they be willing to go through that ordeal again? I proposed to lead them into emotionally charged areas that had not been developed in the initial interviews; would they agree to follow? Eleven years had passed since they had been interviewed by Eric Lasher; would their memories of those years of horror still be good, or would they be vague and distorted?

Normally, in the reconstruction of current history based primarily on eyewitness accounts, there are second and even third sources to verify the facts. But in this case, many of the events involved only the individuals themselves and were known only to them.

As I met the survivors and began to explore their stories with them, I realized that while many of the safeguards of conventional reportage might be unavailable, there were other tests of credence that could be applied. The first was plausibility: did the story I was being told ring true and did it jibe with the accounts of others who had confronted the same dangers and difficulties? The second was consistency: did the story hold together, retain its form and adhere to the same facts in the face of persistent questioning? The third was comprehensiveness: was the story large in scope and vividly recalled, and did it accord with the historical record?

As a reporter I am satisfied that I have done everything I could possibly have done to authenticate these stories. If I have used my own reason to resolve certain inconsistencies, it has always been in accord with the canons of historical reconstruction, where there was overwhelming probability that the event occurred in the manner I recounted it. And if, in certain rare instances, I have given the benefit of the doubt to what, after all the above tests had been met, still seemed like a too miraculous account of personal survival, it was because I had learned in the course of writing this book that nothing could be more miraculous than the survival of a Jew in Berlin during the last years of World War II.

Leonard Gross

Bear Valley, California

November 1981

FOREWORD

W HEN A DOLF H ITLER took power in Germany at noon on January 30, 1933, some 160,000 Jews were living in Berlin, approximately one-third of a German-Jewish population of 500,000 persons who, by and large, considered themselves at least as German as they were Jewish. During World War I there had been no more loyal German subjects than the Jews, but by September 1, 1939, when World War II began, the Jewish population had been cut in half. Mostly this was a result of the emigration of Jews fleeing the physical and economic abuses that had become endemic in the Third Reich, but to some extent it was a consequence of the suicides, disappearances and murders that were the harbingers of destruction not only for the Jews remaining in Germany but for somewhere between 4,000,000 and 5,500,000 other Jews inhabiting lands overrun by the German blitzkrieg.

Exactly how many Jews were murdered during the Holocaust may never be known, but the Nazis genocide itself is the best documented crime in history. The manner in which they proposed to exterminate these Jews had evolved over several years through a series of orders and experiments, culminating in a conference held in January 1942, in a suburb of Berlin called Wannsee, to coordinate the efforts of the various agencies involved. The conference, convened by Hitler, was presided over by Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Security Service and deputy chief of the Geheime Staatspolizei, or Gestapo, the Secret State Police. The minutes of the meeting, attended by second-level state and party functionaries, were written by Karl Adolf Eichmann, who served under Heydrich as supervisor of the Reich Center for Jewish Emigration. At the meeting Heydrich reviewed the essentials of Nazi policy, carefully avoiding such words as killing or extermination or liquidation. The Jews would continue to be resettled in slave-labor camps in conquered lands, principally Poland, where the weak among them would be eliminated immediately and the stronger would be worked until they dropped, at which point they too would be eliminated. The only Jews to receive special treatment would be those born in Germany who were now over sixty-five, those who had received the highest honors for service in World War I, invalids, Jewish officials, and Jews so prominent that their disappearance might somehow compromise the Reich. These privileged Jews could be sent to Theresienstadt, an old Bohemian town, where a model ghetto had been constructed to contain them as well as demonstrate Germanys humanity to the outside world. As things worked out, Theresienstadt proved too small to contain all the Jews who were shipped there, and many were ultimately sent to Auschwitz and their deaths.

Numbers of extermination methods had been tried, but the one the Nazis finally settled on had been developed between December 1939 and August 1941, when some 50,000 mentally deficient or disturbed Germans were gassed to death in rooms designed as public showers. Those deaths had aroused much anguish among the public, although the only outcry was contained in bitter allusions that appeared in death notices in the press. The same men who had conducted the mercy killings program in Germany were sent to the east to build the mass extermination facilities, and the gassings in the east began soon after they had ended in Germany.

One feature of the Final Solutionthe Nazis euphemism for extermination of the Jewswas paramount and underlay the discussions at Wannsee. The actual killing of the Jews was to be top secret, in order to avoid, or at least minimize, resistance among the victims and objections by the German people, as well as by neutral nations. One measure of the Nazis success in disguising their intentions was the response of the Jews themselves. Many being resettled followed the Nazis suggestions and brought their remaining valuables with them, which the Nazis of course confiscated after the owners had been put to death.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The last Jews in Berlin»

Look at similar books to The last Jews in Berlin. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The last Jews in Berlin and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.