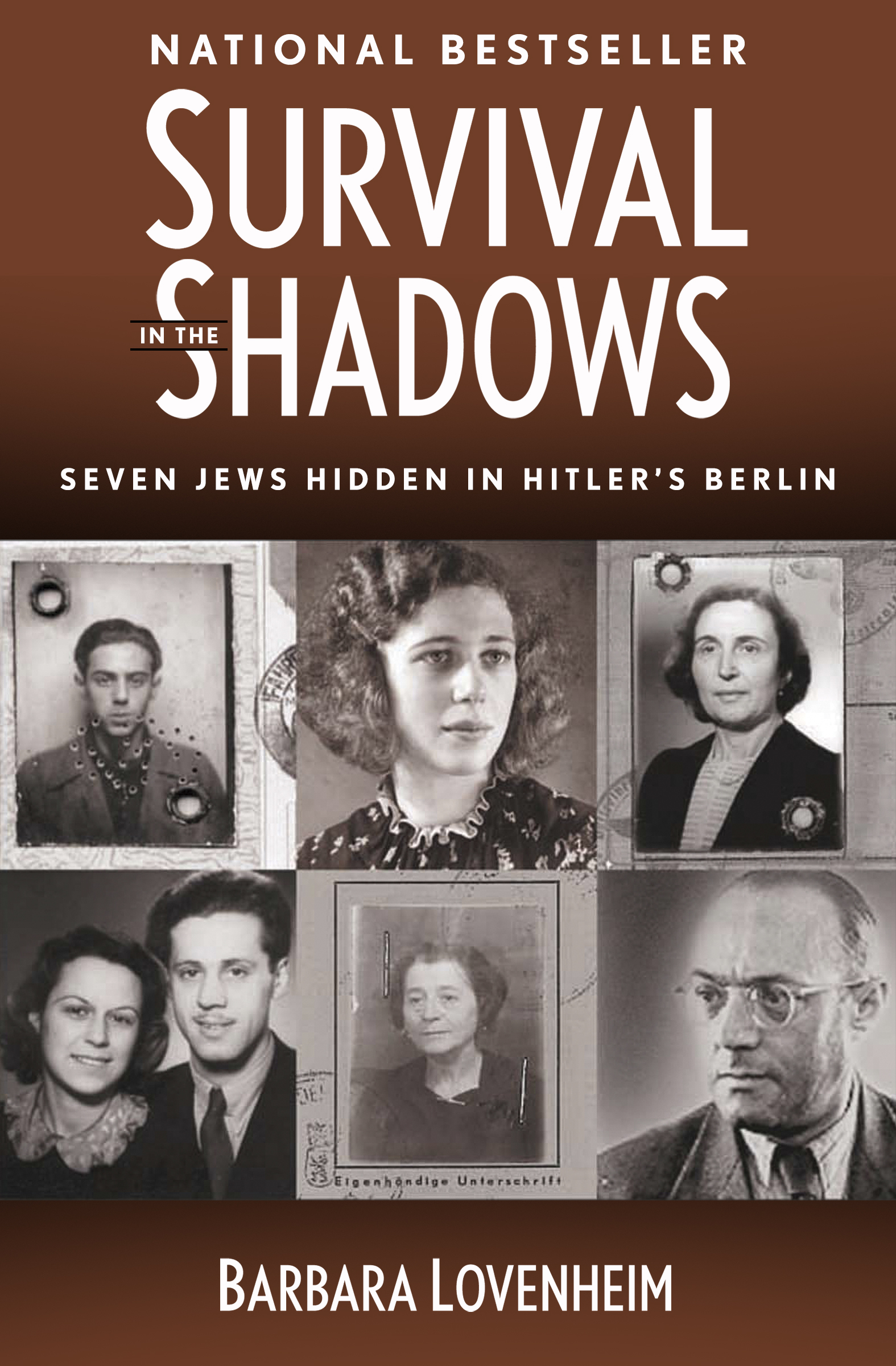

Survival in the Shadows

Seven Jews Hidden in Hitlers Berlin

Barbara Lovenheim

Whoever saves a single life is as one who has saved an entire world.

Inscription on the medal awarded to Righteous Gentiles

by Yad Vashem

Contents

Introduction

I stumbled on the extraordinary saga of the Arndt, Lewinsky and Gumpel families quite accidentally in my hometown, Rochester, New York. During the course of a visit there in 1998 my friend and colleague Barbara Appelbaum, who directed the Center for Holocaust Awareness and Information, asked me to edit a book with her profiling Holocaust survivors from Germany and Austria who lived in the Rochester area. When I read a transcript describing how Ellen and Erich Arndt and five other family members hid as a group for over two and a half years in the heart of Berlin, I was stunned.

Like many other American Jews, I subscribed to the theory that all Germans were overtly or covertly anti-Semitic. While I knew stories of Jews who had been protected by non-Jews in countries such as Holland, France and Belgium, where most ordinary civilians were fiercely opposed to Hitler, I could not imagine that a group of seven Jews could have survived in the heart of Berlin under Hitlers nose, so to speak.

I decided to meet the Arndts and propose writing a full-length book on their life in the underground. They were receptive but wary. Not surprisingly, several journalists had approached them through the years, but, for one reason or another, a book had not materialized. They were also understandably nervous about entrusting intimate details about this important part of their life stories to another person.

We decided to proceed with the proviso that we work closely as a team. The book we envisaged would not be a typical as told to memoir, because there were three people and three voices involved: Ellen and Erich Arndt and Erichs sister Ruth Arndt Gumpel. Instead, it would be a narrative based on the groups collective memories and transcripts of their journals and other documents.

The Arndts primary motive was to thank the more than fifty non-Jewish Germans who risked their lives to save them during their perilous struggle to escape the Nazis during the war. While five of these protectors the Gehres, the Khlers, the Schulzes, the Treptows and the Santaellas were officially honored by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Israel, as righteous Gentiles, there were many others who played minor but equally important roles. As Ellen often reminded me, the people who knew their true identities and did not say anything to the German authorities were as important as the people who actively provided them with food and shelter. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

Ruths husband, Bruno Gumpel, whom she met during her years in the underground, died in 1996 from cancer. I worked with Ellen, Erich and Ruth from 1998 to 2002 and I came to know them all very well. What I valued most about them was their openness and their lack of rancor and bitterness. Despite the deprivations and human losses they suffered as a result of Hitlers barbarous policies against the Jews, they vowed that they would not allow him to rule their lives. Defying Hitler and the Nazis, to them, meant cultivating a zest for life and, ultimately, telling their story to the world.

When I met Ellen and Erich, they lived in an airy two-bedroom apartment in a suburb of Rochester in a building next to my mothers apartment house. The Arndts moved to Rochester in 1960 from Hempstead, New York, where they settled after emigrating to the U.S. in 1946. If it were not for their heavy German accents you would assume they were typical upper-middle-class Americans. Ellen was slim with short grey hair. She usually dressed casually in slacks and shirts, sporting a gold chain with a Star of David inlaid with tiny blue stones around her neck. She was incredibly bright and funny, with a dry, ironic sense of humor; outspoken when she felt the occasion merited it and extremely generous to her friends and family. Erich had a full head of thick grey hair and wore glasses. Several years before we met he retired from his job as a division manager with the Alliance Tool and Die Company; he tuned pianos in his spare time. He suffered from diabetes and sometimes had to use a cane. Less outgoing than Ellen, Erich was the decision-maker in the family, and he had a similarly understated, wry sense of humor.

After moving to Rochester, the Arndts joined a Reform synagogue, where Erich was president of the congregation for several years. Ellen held a leadership role in the sisterhood. They were no longer so active in their temple when we met, but Ellen continued to give talks to schoolchildren and college students about her experiences during the war. Erich tended to shy away from public appearances; he preferred to read and listen to music.

The Arndts had two daughters and five grandchildren. Their younger daughter, Rene, still lives in Rochester. The Arndts oldest daughter, Marion, lives in Michigan; she and her husband have one son. Ellen and Erich were very family-minded: they frequently took their grandchildren to lessons and concerts and also cared for them after school; they also helped their granddaughter Timna, who worked as a nurse, with babysitting and chores. They often put up their other grandchildren when they came to town for a visit, hosted holiday dinners and mediated in family crises. Timna is now married and has four young children; her sister Yona is a medical researcher, and her brother Josh is a computer technician.

Erichs sister, Ruth Arndt Gumpel, was also extremely family-oriented. She had two sons: Larry, an audio supervisor for CBS, and Stanley, a technical specialist for pre-press. Ruth and her husband, Bruno Gumpel, moved to Petaluma, California, from their home in Queens, New York, to be near Stanley and his son Alex after Bruno who passed away several years after the move retired from his position as a technical supervisor with CBS.

Ruth, who worked in New York as a pediatric nurse, was lively and irreverent, with a wicked sense of humor. She had a penchant for stylish hats and colorful scarves. She belonged to a poetry-reading group in Petaluma, where she made a number of new friends. She also volunteered in a local hospital as well as an animal shelter. But her chief focus was helping out with her teenage grandson, Alex, who is now in his late twenties.

Ellen and Erich were extremely close to Ruth. They spoke to each other on the telephone every Saturday promptly at noon and they visited often. They all participated actively in the creation of this book. They wanted the world to know that there were some good Germans who were more responsive to their conscience than to Hitler. In a society where everyone is guilty, it is sometimes argued, no one is responsible. That was not the case in Nazi Germany.

Roughly 5,000 Jews went into hiding in Berlin and possibly another thousand did so in other German cities. About 1,400 are reported to have survived. Of these survivors, the Arndt-Lewinsky-Gumpel group is the largest known group to have survived as a unit. Perhaps owing to the anti-German sentiment that prevailed in the U.S. after the war and the persistence of anti-Semitism in post-war Germany, it was not until 1980 that scholars took note of the Arndts incredible story and the help they received from German Gentiles. In that year, Ellen and Erich Arndt and Ruth and Bruno Gumpel were flown to Germany by the Berlin Senate; there they were honored with other former Berliners who were forced to leave Germany because of the Nazis. In 1987 Larry Gumpel taped a two-hour video on their underground years that was donated to the Holocaust Center of the Jewish Community Federation of Rochester. In 1990 the two couples were again flown to Berlin and interviewed for an exhibition, The Jews of Kreuzberg, that was displayed in a house on Adalbertstrasse in Kreuzberg. In January 1991 Ruth and Bruno were interviewed by the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City.