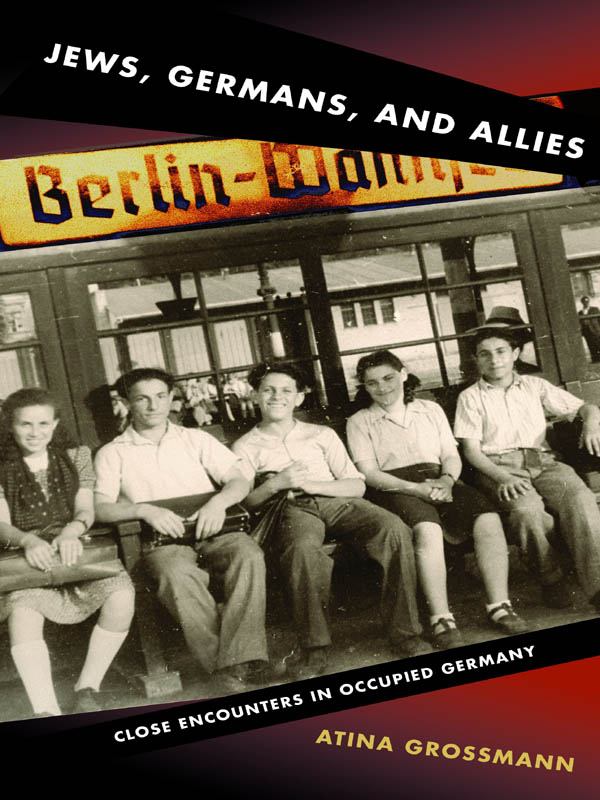

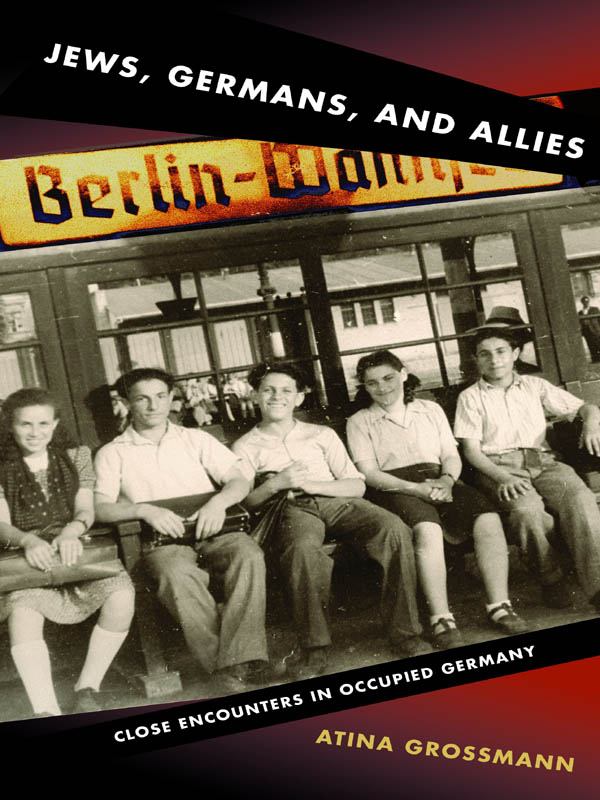

Jews, Germans, and Allies

Jews, Germans, and Allies

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS IN OCCUPIED GERMANY

Atina Grossmann

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2007 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

All Rights Reserved

Third printing, and first paperback printing, 2009

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-691-14317-0

The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows

Grossmann, Atina.

Jews, Germans, and Allies : close encounters in occupied Germany / Atina Grossmann.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-08971-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. JewsGermanyHistory19451990. 2. Holocaust survivorsGermanyHistory20th century. 3. JewsGermanyPolitics and government20th century. 4. GermanyEthnic relations. I. Title.

DS134.26.G76 2007

940.531814dc22 2007019952

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon

Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

In memory of

Toni Bernhard Busse, 18841943?

Gertrud Dewitz Grossmann, 18731943?

Contents

Illustrations

Preface

Where Is Feldafing?

A S THE N EW Y ORK C ITYBORN CHILD of German Jews, I grew up in a world of refugees where European Jewish life was deemed to have come to its catastrophic end in 1943. German Jews had fled throughout the globe. My parents had landed in New York after an adventurous decade in Iran and, for my father, wartime internment as a German enemy alien by the British in the Himalayas. Relatives and family friends sent photos and blue aerogrammes with exotic stamps from Israel, England, South Africa, Argentina, Denmark, France, and Japan (and eventually, after Stalin died, even from the Soviet Union) to our increasingly comfortable German-speaking enclave on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Germany and Jews, I thought, had been irrevocably separated by a drastic and traumatic historical rupture since 1941, when the last emigration possibilities shut down, and 1943, when Goebbels promised a judenfrei Berlin and the deportation trains pulled out of the city toward the East.

I should have known better. The Jews, Germans, and (mainly American) Allies whose encounters are chronicledand sometimes overlapping identities juxtaposedin this book, all figure in my own family history. My maternal grandfather, part of whose story I tell here, spent the first postwar years in the Berlin he had never left. He had escaped into hiding in 1943, one of the remnant of German Jews who survived within Germany. His Berlin-born-and-raised nephew, by wars end an American GI, found him in July 1945 when the Americans took over their sector of the city. And, every summer of my childhood and adolescence, we traveled to Bad Homburg near Frankfurt to visit the family of my fathers younger brother. He was a convert to Catholicism who had remained in Germany with his wife and five half-Jewish children until he was deported to Auschwitz in 1943. He, too, had survived, first as an inmate physician in the infirmary of the slave labor sub-camp Monowitz, and then as a prisoner in Mauthausen, where he was liberated by American troops. He died in the early 1950s, a belated victim of Nazi extermination. By then, however, he had had a sixth child, made it through the chaos and misery of German defeat to become the director of a German hospital, andanother story included in the bookjoined my father in the struggle to reclaim some of their aryanized property in Berlin. So the blue aerogrammes that I found, many years later, in such abundance among my parents yellowing file folders were filled with stories about Germans, Americansand Jewsin postwar Germany. But my grandfather had left Berlin for New York in 1947, and my cousins in Bad Homburgthe only close relatives I had who were remotely near my own agewerent really Jewish.

It was only in 1971, when I was a college student traveling through Europe and Asia with my then-boyfriend Michael, that I first consciously encountered a Jewish history in postwar Germany quite separate from the refugee and migr tales on which I had been raised. I knew virtually nothing about the strange historical circumstance that marked Michaels family stories: that by 1946/47, three years after Germany had been declared judenrein, and within a year of the Third Reichs defeat, there were again a couple of hundred thousand Jews, mostly not German, living onalbeit defeated and occupiedcursed German earth (verfluchte deutsche Erde). The U.S. passport Michael carried listed his place of birth simply as Germany. This was a source of great irritation to him, a kind of insult added to injury for someone who had been born in the displaced persons (DP) camp where his Romanian parents had finally found refuge after spending the war in various Nazi and Hungarian labor and concentration camps. Michael and I journeyed to Baie Mare, a medium-size Romanian town near the then-Soviet border where his Aunt Gittie and Uncle Shimon, fellow DPs who had returned to Romania, were awaiting their exit permits for Israel. On the train, I peered at the offending passport once again and finally asked him, Michael, where actually were you born? He responded with a name that I had heard frequently in conversation at his parents house in the Bronx but had never thought to inquire about: Feldafing. And where, I now wanted to know, was Feldafing? Michael paused for a moment, as if this was a question no one had ever needed to ask, and then said, quite definitively, near Bremen.

And there the matter rested for over twenty-five years, until I began working on the topic of Germans and Jews in postwar Germany and discovered that Feldafing was nowhere near Bremen. Actually, it was quite at the other end of Germany, in Bavaria on the shores of the Starnberger See near Munich. Being the type who never quite lets go of old friends, I knew where to find Michael (at a newspaper editorial desk), called him up, and demanded to know why he had told me that Feldafing was near Bremen when it so clearly was not. We puzzled about this peculiar confusion for several minutes until we both realized what should have been obvious. When Michael, who had arrived in New York at the age of three, was growing up, he continually heard two place-names associated with Germany: Feldafing and Bremerhaven. Feldafing was the site of the displaced persons camp in which his family had lived, and Bremerhaven, the port from which his family had finally departed for the United States. So it made complete sense that, in his childish imagination, and preserved into his adult memory, Feldafing and Bremen merged into one contiguous area. As far as he could make out, no place in Germany existed or mattered other than an extraterritorial American- and UN-administered refugee camp filled with Jewish survivors and the city that signified separation from the bloodsoaked soil of Germany and Europe.

In fact, however, as Michaels mother Ita confirmed in an oral history interview in 2003 shortly before she died, the story of Jewish life in occupied Germany and indeed Michaels own familys experience were much more complicated. In her account, detailed in , Ita talked with great verve about her relations with local Germans in and around Feldafing, revealing that the space occupied by Germany and Germans in Jewish DP life (and, conversely, by Jews in German life) was much more capacious and multifaceted than Michaels version or most historical accounts would suggest.

Next page