GERMANS AGAINST GERMANS

OLAMOT SERIES IN HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES

Irit Dekel, Jason Mokhtarian, and Noam Zadoff

Aufbau Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin 2008

Copyright 2008 Moshe Zimmermann

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.org

2022 by Olamot Center

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2022

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-06229-1 (hdbk.)

ISBN 978-0-253-06230-7 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-253-06231-4 (web PDF)

To my parents,

Johanna (Hannah) ne Heckscher and Karl (Akiva) Zimmermann,

who by being forced to leave Germany in 1937 and 1938, respectively,

avoided the fate of the Jews who stayed behind.

CONTENTS

JSSJewish Social Studies

LBYBLeo Baeck Yearbook

VfZVierteljahreshefte fr Zeitgeschichte

ZfGZeitschrift fr Geschichstwissenschaft

GERMANS AGAINST GERMANS

THE DECLINE OF GERMAN JEWRY drew attention in various contexts even before the National Socialists acceded to power. As early as 1911, Felix Theilhaber published a scholarly work titled exactly that, discussing the demise of the Jews of Germany from demographic and sociological points of view.

From 1933 onward, the word decline was unquestionably valid in describing the history of German Jewry, although from a diametrically opposite directionin other words, the days of assimilation and equality had passed. From that time on, the war cry Germany, awake! Jews to the stake! was heard everywhere in the cities and villages of Germany and became a guiding principle in German authorities operative policies. In a certain sense, the Middle Ages had reemerged in Germany, ushering the Jews of Germany into a process of disentitlement, discrimination, and ultimately deportation from the German lands. Accordingly, Gustav Krojanker, a Zionist who had emigrated to Palestine, titled his Hebrew-language booklet, published in 1937 in Palestine, The Rise and Fall of German Jewry. in which 1918 is seen as the year of demise. For Bruer, the Weimar Republic already belongs to the postemancipation era. Even the Leo Baeck Institute, devoted to research on German Jewry and its culture, long invested scanty attention to the fate of German Jewry after 1933. In this state of affairs, one is almost tempted to say that the National Socialist policies sank roots in historiography as well: from the historians standpoint, it was in 1933 that German Jewry crossed its finish line.

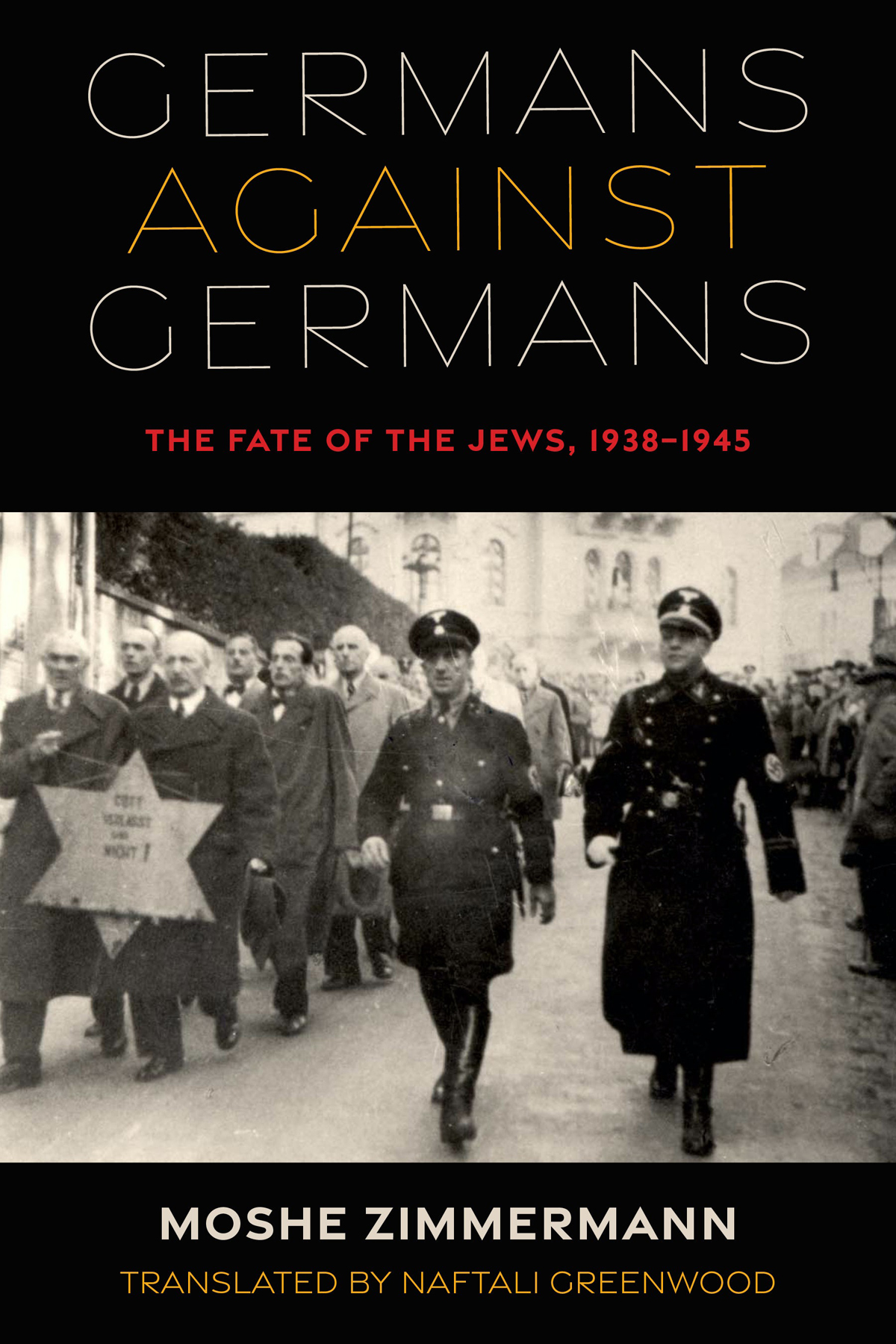

And if, all these postulates notwithstanding, the history of German Jewry under National Socialist rule after 1933 is described, this period is examined, by and large, separately and out of context with everything that preceded it, as though the National Socialist authorities not only introduced a new policy toward the Jews but also created a new German Jewry. Even if in no way intended to document the continuation, and least of all the end, of German Jewish history, this firmly demarcated investigation of post-1933 developments, in disregard of everything that happened before, has to some extent become a prequel to the history of the Holocaust in its broad sense. It usually spans the 19331938 period, up to the eventthe pogrom of November 9known as Kristallnacht. What happened to the German Jews after 1938 is assimilated into and embedded in the story of the Holocaust, since when they deal with World War II, historians and their readers obviously train their gaze on the history of European Jewry at large.

Thus, the fate of German Jewry in its final decline, from 1938 to 1945

between the November pogrom and the end of World War IIis poorly represented in the historiographic literature and emerges either as a negligible part of the history of the Holocaust or as a small appendix to German Jewish or general history. Namely, it is marginalized or, in the best case, set within a context that transcends the history of German Jewry. As a rule, even Gtz Alys approach to the Final Solution since 1995, and his take on the dispossession of the Jews by the Nazi regime in his 2005 book, published by the Leo Baeck Institute, and History of the Holocaust: Germany, a collection of articles published in two voluminous tomes under the editorship of Abraham Margaliot and Yehoyakim Cochavi. Only about one-fourth of the content of these works is devoted to the 19381945 period; the remainder takes up the 19331938 years. The authors of Jews under the Swastika, published in 1973 in the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), also fail, for both historiographic and ideological reasons, to pay close and consistent attention to the 19391945 interval, even though in their subtitle they promise to discuss the Persecution and Extermination of the German Jews 19331945.

This chapter in the history of German Jewry, however, deserves more than an encyclopedia entry, such as that in Pinkas Hakehillot: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, published by Yad Vashem, and is owed a description that exceeds that of an appendix. It deserves its own synthesis, sedulous investigation, a monograph, and close photography, not only because no such things have yet been published but also, and mainly, because the specifics of German Jewish history in this context should be clearly sketched within the framework of the general history of the Holocaust, the Third Reich, and World War II, and the continuities and discontinuities of this communitys history should be given emphasis.

Unlike European Jews outside of Germany, who could clearly differentiate between the Germans and the Nazis and the collective that they perceived as us, for German Jews the enemiesthe criminals and their supportersalso in fact belonged to us, irrespective of how they were understood. The singularity and tragicality of this nexus of criminals and victims germinates not only in the lengthier duration of the Holocaust in Germany, starting in 1933 and not only when the war began in 1939, but also in the disposition of the struggle and the war, the deportations and the murders, as Germans against Germansat least from the standpoint of the victims, the Jews of Germany.

The road to correcting the status of this interval in history is already being paved, and important strides down it have been taken since this book first appeared in 2008 in German. The past two decades have seen a perceptible upturn in historiographic interest in German Jewish history of 19381945. Several important aspects of the topic have been thoroughly researched and analyzed. Much new information and knowledge have been amassed, most involving the use of new methodological approaches. The works of Beate Meyer, Wolf Gruner, Frank Bajohr, Avraham Barkai, Alexandra Przyrembel, Rivka Elkin, Konrad Kwiet, and Doris Tausendfreund are impressive examples. Archive research continues relentlessly. The Bundesarchiv (the German Federal Archive), for example, launched a documentary project on the deportation and murder of European Jewry, and volumes 2, 3, 6, and 11 concerning the Jews of the Reich from Kristallnacht to the end of the war have already appeared. In addition, survivors steadily continue to publish memoirs. Despite all these efforts, however, no historical synthesis has yet been created devoted solely to this chapter in history on the basis of study of the monographs that have been published on the topic in the meantime. By synthesis, I mean the history of a group of people in the course of one period, in the sense of a self-standing chapter grounded in existing documents and secondary literature dealing with secondary aspects. This is the rationale behind the study that follows. My purpose is to describe and explain a phenomenon, a multifaceted connection of things, without drowning in innumerable unnecessary details. As in all historiography, this work of course presents only an interim reckoning that will surely expand and improve as research progresses. As evidence, the twelve-year period between the publication of the book in German (2008) and its translation into English has seen the appearance of a respectable list of new books and articles on the topic.