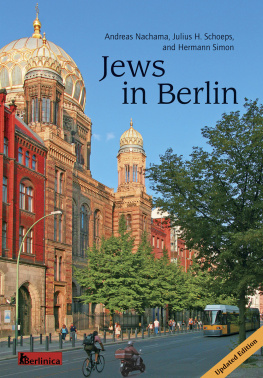

Praise for Jews in Berlin

Berlin is now a major destination for American Jewish tour groups. Jews loved Berlin a city that alternately freed and destroyed them. Carefully recounting this confounding tale, Jews in Berlin honors the complexity of an unfathomable relationship.

Ira Wolfman, The Jewish Book Council

Finally, a comprehensive book on the history of Jews in Berlin has arrived! Never has there been such a complete overviewsupported by wonderful illustrations.

Berliner Zeitung, Berlins largest daily newspaper

This book offers an outstanding and thorough overview of more than seven centuries of Jewish life in Berlin. An indispensible read on Berlins cultural history.

Portal Kunstgeschichte, online magazine on art and art history

this book [has] become a captivating read that promises a wealth of enjoyment, especially for a non-academic public.

taz, die tageszeitung, Berlins liberal daily newspaper

This book presents centuries of history of Jewish life in Berlin as a vivid and comprehensive impression of development, illustrated by a richness of documents, profiles, and images.

Katholische Kirchenzeitung, German Catholic weekly news magazine

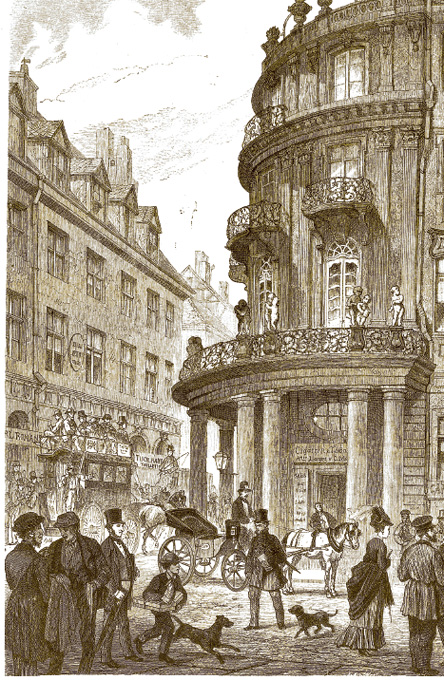

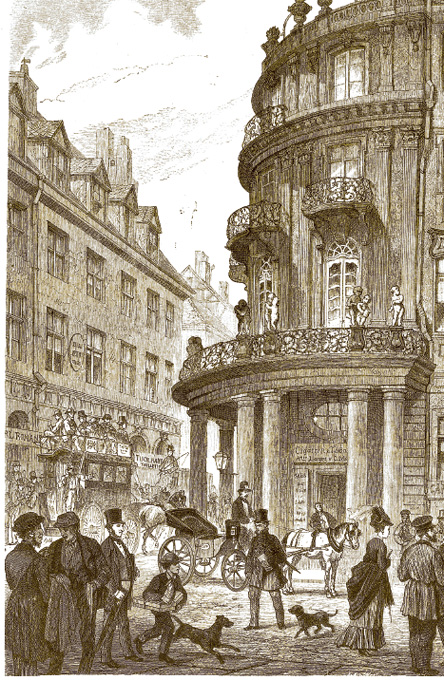

The Ephraim Palace at the corner of Poststrasse and Muehlendamm.

Wood engraving after a drawing by Doepler, around 1890.

This publication was sponsored by:

Jdische Kulturtage Berlin

Moses Mendelssohn Zentrum fr europisch-jdische Studien

Stiftung Neue Synagoge BerlinCentrum Judaicum

German Consulate, New York City, NY

Allianz of America

The original translation was enabled by: Partner fr Berlin

ISBN print: 978-1-935902-60-7

ISBN ebook: 978-1-935902-61-4; 978-1-935902-62-1, 978-1-935902-63-8

LCCN 2013930146

Originally published in German as Juden in Berlin

2001 by Henschel Verlag, Berlin

Original English translation 2002 by Henschel Verlag, Berlin

http://www.henschel-verlag.de

Updated English translation 2013 by Berlinica Publishing LLC, New York, NY

www.berlinica.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of Henschel Verlag and Berlinica Publishing.

Front jacket photo: The New Synagogue on Oranienburger Strasse,

Photo: Eva C. Schweitzer

Back jacket photo: Andreas Nachama, Julius Schoeps, Hermann Simon

Photo: private

Essays by Flumenbaum, Schoeps, Schtz, Brenner, Nachama translated by Michael S. Cullen.

Essay by Simon translated by Allison Brown.

Essay by Kessler/Anchuelo translated by Cindy Opitz

Editor and photo researcher: Michael Philipp

Editor of translation: Miranda Robbins

Original jacket design by Morian & Bayer-Eynck, Coesfeld

Jacket design of the new American edition: Eva C. Schweitzer

Book design by Typografik & Design, Berlin

Printed and bound by Lightning Source, USA

Contents

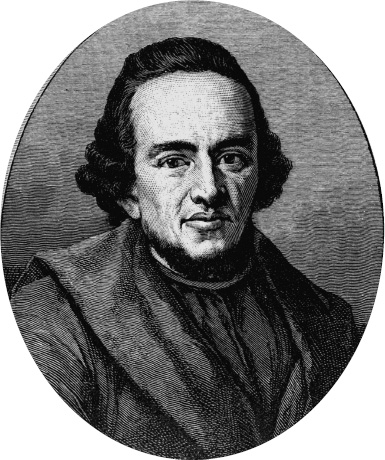

Moses Mendelssohn (172986).

Copper engraving after a painting by Anton Graff

Foreword

Berlin is a destination for American Jewrya tourist attraction for every tour of the United Jewish Appeal, every synagogue travel program, and every Jewish heritage journey. This unimaginable development is a reality that has added immeasurably to bolstering the economy of this once and future world capital. It has also added immeasurably to Germanys reputation as a nation willing to take historical responsibility for its crimes, and committed to honoring the memory of its once-thriving Jewish community. The city associated with glamour, decadence, sophistication and terror has become a city of serious scholarship and research on Central European Jewry, which, of course, includes glamour, decadence, sophistication and terror.

It also includes a reemergence of contemporary Jewish cultural and religious life, mainly through the influx of Russians, Israelis, and Americans. Berlin has become a haven for artists, musicians, writers and other creative types who can afford to live in this relatively inexpensive but increasingly cosmopolitan European capital with easy access to Vienna, Prague, Budapest, Paris, even London. Many, however, see no need to get away Berlin and its environs provide a rich and diverse landscape.

This is not unlike the atmosphere of the 1920s, where the variety of options attracted liberals, conservatives, aesthetes, scientists, theologians, democrats and anti-democrats. That was the Weimar Republic. The contributions to this volume, however, cover virtually the entire spectrum of Jewish life in Berlin from the 13th century to the present. It is clear that life for Jews did not always offer such an abundance of lifestyle choices. Until Emancipation of 1870, opportunities were circumscribed and limited. After that, until 1933, Jews in Germany (many of them living in Berlin) had more professional, political and personal opportunities than Jews anywhere else in Europe. Yesrestrictions were still in place, especially in the military and universities, but the innovative initiatives of the Jewish population living in the most open metropolis on the continent resulted in scientific breakthroughs, unprecedented legal and social legislation, and modern popular culture.

Berlin Jewry, like all of German Jewry, dispersed around the globe after the Nazis came to power, taking refuge in places as diverse as Guatemala, Palestine, South Africa, Shanghai and America. New York in particular was the beneficiary of the energy and entrepreneurship that the Berliners brought with them. The opera, the philharmonic, the science faculties of universities, the fields of medicine and sociology, the disciplines of law and civil libertiesall these as well as journalism, advertising, education, and religionwere transformed by the contributions of the new immigrants. Many could continue in their chosen professions, many needed to be retrained, some were so young they easily acculturated; some were too old to do anything but continue to meet each other.

Amazingly enough, their children, grandchildren, nieces, nephews, and friends still feel connected to Berlin. The fascination with this heritage is not hard to understand. The stories they heard from those who were forced to leave their beloved Heimat were almost all good. By 1930, most members of Berlins Jewish community had established themselves as Berliners a vibrant and dynamic population. They were urban, middle class, educated and often prosperous. Four percent of the population was Jewish but they constituted a far larger percentage of doctors, lawyers, merchants and bankers. They owned twenty percent of the commercial enterprises, including butcher shops, department stores, and newspapers. Jewish artists, writers, musicians and actors contributed daily to Berlin as the entertainment Mecca of Europe. Max Reinhardt, for instance, director of the Deutsches Theater, turned it into one of the most renowned in Europe. He also turned it into one of the most profitable artistic enterprises of its timeby 1931 Reinhardt owned twelve theaters with more than 10,000 seats. By 1934, the Nazi seizure of the theatre was complete, and almost all of the Jewish owned businesses were first boycotted and ultimately aryanized or destroyed.