ALSO BY AGATA TUSZY SKA

Vera Gran: The Accused

Lost Landscapes: In Search of Isaac Bashevis Singer and the Jews of Poland

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Translation copyright 2016 by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., Toronto.

Originally published in Poland as Rodzinna Historia Lku by Wydawnictwo Literackie, Krakw, in 2005 . Copyright 2005 by Agata Tuszyska and Wydawnictwo Literackie. This translation is based on the French edition originally published in France as Une histoire familiale de la peur by ditions Grasset & Fasquelle, Paris, in 2006 . Copyright 2005 by Agata Tuszyska, copyright 2006 by ditions Grasset & Fasquelle.

www.aaknopf.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tuszynska, Agata, author.

[Rodzinna historia leku. English]

Family history of fear : a memoir / Agata Tuszynska ; translated by Charles Ruas from the French of Jean-Yves Erhel.

pages cm

ISBN --- 41370 - (hardcover : alk. paper)ISBN --- 87587 - (ebook) . Tuszynska, Agata.. Tuszynski family.. JewsPolandBiography.. Warsaw (Poland)Intellectual life. I. Ruas, Charles, translator. II. Title.

DS..TA 2016

. 2089 ' 9240438 dc 2015020551

ebook ISBN9781101875872

Cover photograph courtesy of the author

Cover design by Kelly Blair

v4.1

ep

Contents

TO MY PARENTS

IN MEMORIAM

Marilyn Goldin

(19412009)

Who began the translation of this work before illness took her away.

Victoria Wilson

Charles Ruas

Agata Tuszyska

T his book has been in me for years. Along with this secret. From the instant I found out I was not who I thought I was. From the moment my mother told me she was Jewish.

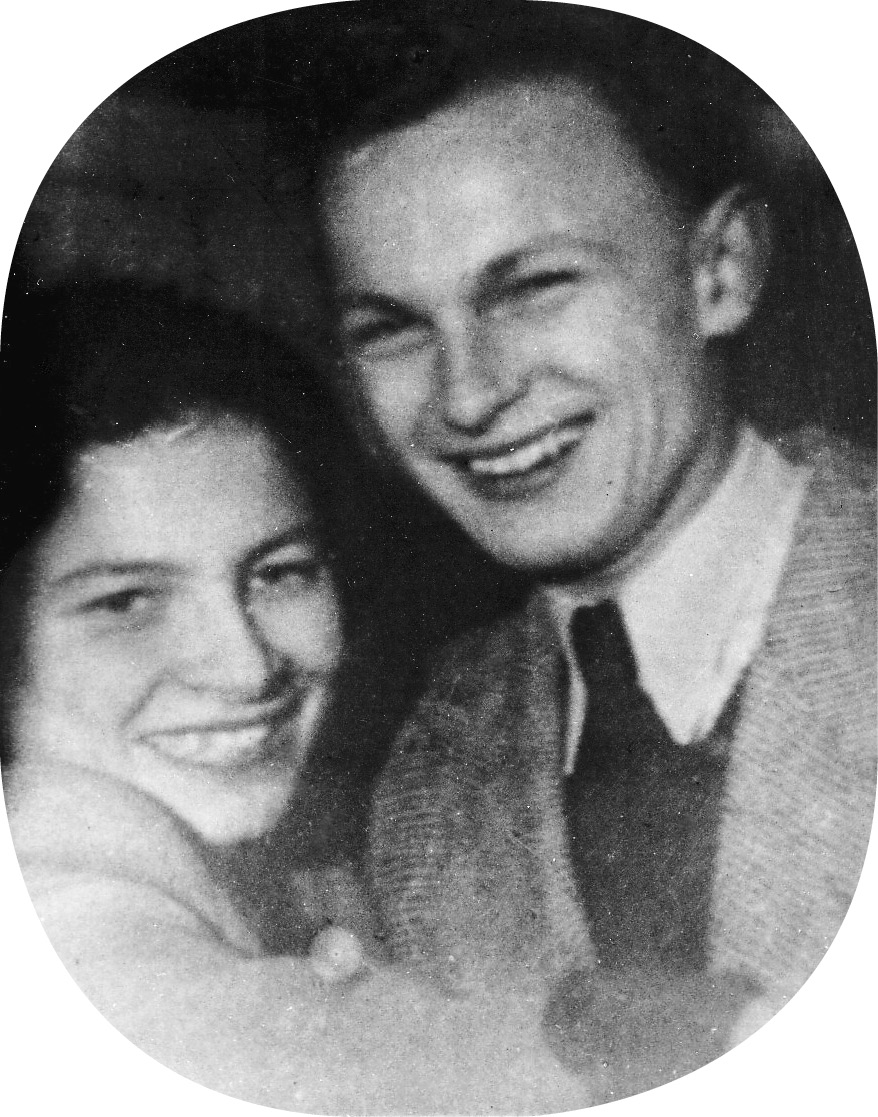

I was born in Poland, in Warsaw, several years after the war. I had blue eyes and blond hair, a source of great pride to my mother, whose own eyes and hair were dark.

Today, I realize she wanted a Polish child, for fear of the fate her daughter might inherit otherwise, a fate like her own. And even though the war was officially part of the past in a new socialist Poland, where everyone was equal by definition, she resolved to obscure her origins.

We are our memory. We are what we remember. And what others remember about us.

Even more than that, I often find myself thinking, we are our lapses of memory. We are what we forget, what in self-defense we blot out of our memory, chase from our consciousness, avoid in our thinking. We conceal memories to make life easier or lighter, so it will not hurt.

I do not remember when my mother told me she was Jewish. I remember nothing about itnot the day, nor the season, nor the place; not whether we were sitting at the table or by the window; not the tone of her voice, nor the color of her words. I have no memory of any such conversation. Maybe she told me that she hid in a cellar during the war. That was not unusualmany Poles were forced to hide in cellars or attics. Maybe she said she had to run away from the Germans, escape, like many othersPoles who were hunted down by the Nazis, rounded up at work, machine-gunned in the streets and forests, sent to the camps.

She does not remember exactly how she went about it, but she certainly did not begin with the persecutions and the walls, the marks, the distinguishing insignia of the yellow star. She began by telling me stories. About the curtain, at first. Then, about the chinchilla coat and the muff. Then about the coach in front of the ghetto wall. Nothing more direct. Little by little. To make it easier.

She wanted her child to be without a stigma. She was happy to have brought a little blue-eyed blonde into the world. This little girl had a proper Polish father. She taught me how to live in this country.

She didnt want to weigh me down with a burden heavier than I could bear. She didnt want her child to have to grow up with a feeling of injustice and fear. In her estimation, one could always broach the subject when a child was capable of handling it and taking care of herself.

She is sure she told me when I was nineteen. I have no reason not to believe her.

Every family has a story. Many Polish families have tragic ones. In those days, people did not always tell children about their hardships during the warthe Resistance, the Home Army, participation in the uprisings in Warsaw and fighting in the forests. It took them years to start talking about what they had been through, about the pain as much as the heroism. These stories, when they finally came out, drew the generations together and gave them strength. But my mothers experience was not like that. It was more, much more. Not only in the depth of the suffering and tragedy but also in their consequences. There was nothing in it to brag about or cling to, nothing to wear out by retelling. There were no heroic deaths, no patriotic examples, no sacred traditions, no hope for the future. It had to be concealed. This thing.

Years passed before I found the strength to admit it. Before my spirit abandoned its defenses and took it in. I needed time. Without accepting it, to be sure, but still inwardly weighing the possibility. It took about ten years.

Has it happened? Can I say I am Jewish?

No.

Did my mother tell me her war stories? Did she actually tell me, or did she only want to tell them without quite having the strength to go through with it? No, its not enmity that you absorb with your mothers milk. Its fear.

On the subject of the fur coat. It had to be taken out and aired. Especially a coat as respectable as one of chinchilla. Especially one that has been kept in a wardrobe on the Aryan side for years. When Mama and her mother slipped out of the ghetto and reached the safety of their first hideout, they often went for walks after dark. They were afraid of being caught, but they were also hungry for some fresh air and the chance to get their blood moving. My grandmother also wanted her coat to get a good airing. A coat that was already beginning to fall apart, by the way. Fur wears out faster than a human being does. In the end, with a heavy heart, my grandmother had it cut up into small pieces. In a snapshot taken in Zakopane after the war, Mother was carrying a chinchilla muff; the coat didnt make it much farther than that.

Concerning the curtain. In fact, this story is all about salt. My mother and grandmother were hiding in a small apartment at Krasiski Street in the Fourth Colony, where they used to live before the war. The place belonged to two sisters who worked in the neighborhood as domestics. In the kitchens pantry, a curtain with dark blue flowers on it. One night, the boyfriend of one of the sisters, Helenka, came over. Shed made barley soup for him, but she didnt salt it enough. He complained. She went to borrow some salt from a neighbor. Left alone, he decided to find some himself. In the pantry, behind the curtain. Mama was twelve years old and held her breath. Her mother held the curtain closed. He understood. They had to move out.