Authors Note

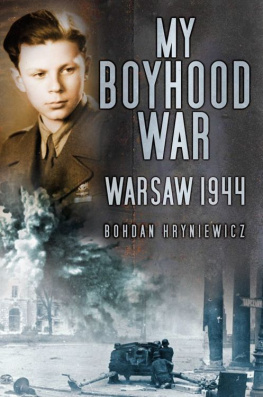

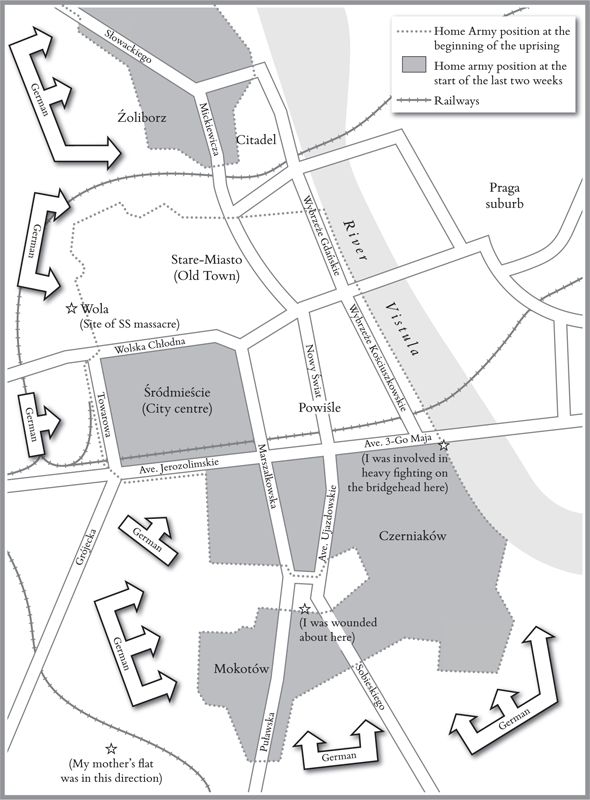

Warsaw Boy was conceived some seventy years ago, when I had just turned sixteen. It was started towards the end of 1944, with notes I pencilled on Red Cross toilet paper while recovering from my wounds in the hospital of a prisoner-of-war camp, in Germany. It was all the captured British medics who were treating me could find for me to write on. As well as my own experiences, these jottings included interviews with other wounded men from the Uprising. My most senior contributor was the lieutenant-colonel who had commanded the northern suburb of oliborz and had clung on to the last western stretch of the Vistula that was still in our hands until all hope of rescue from the Russians across the water was lost.

When I arrived in America as a scholarship student, I typed up my notes and filed them away. I intended, one day, to write a full account of my wartime childhood, culminating in its premature coming of age during the Uprising. Somehow these notes survived the constant disruptions that are so often the lot of the career foreign correspondent.

In the early 1970s, I was living in Cyprus when the Hong Kong-based British philanthropist Norman Marsh, whose yacht sometimes anchored off my home near Kyrenia, helped make it possible for me to take some time off journalism and return to my notes.

I chose to write my story in the form of a very autobiographical novel in which the fiction was mainly limited to changing a few names. One of the reasons why I approached it this way was because, at that time, memoirs tended to be the prerogative of famous people newspaper journalists were rarely considered sufficiently well known. The other was because I thought writing my account in the third person might make it easier to bridge the chasm that existed between a middle-aged English-language journalist and the Polish-speaking boy of some thirty years before. When I had reached the point where I knew I had to stop making changes to my own typewritten script, my wife, Juliet, typed out a final draft of 559 pages about 140,000 words.

It was never published. Agents and publishers suggested changes I wasnt prepared to make. In the summer of 1974, I very nearly lost the manuscript altogether when we had to temporarily abandon our home in Kyrenia during the Turkish invasion of that year. I put it aside and in between reporting on conflicts in the Middle East and the Balkans I was last shot at in Croatia, at the age of sixty-three produced six well-received non-fiction books, including political histories of Yugoslavia and Cyprus. Then, in 2001, the US academic publisher Praeger brought out my Destroy Warsaw! Hitlers Punishment, Stalins Revenge, an historical overview of the Uprising.

Some reviewers notably the retired-US-officer-turned-historian Robert Forczyk regretted that I had provided only the barest details of my own experiences during the Uprising. This whetted my appetite to return to an account of the whole story of my war and, from time to time, I tried turning parts of the novel into the memoir I should have written in the first place. Some pages of the original manuscript were missing, but like many octogenarians, who may not recall all the events that occurred last week things that happened to me in the 1940s often return with startling clarity. That said, they were usually more memorable.

A couple of years ago, I showed some of these revisions to my friend Colin Smith, a writer and former foreign correspondent on the Observer, who, in the words of one reviewer of his work, has built an impressive reputation as a military historian. Colin showed them to Eleo Gordon, Editorial Director at Penguin UK, who liked what she saw and suggested he help me edit my story.

The result is this book.

Andrew Borowiec

Nicosia, November 2013

Altengrabow

Germany, October 1944

Bombs had wrecked some of its buildings but the small towns railway tracks ran through the tidied rubble, and the station itself was still functioning. Dead leaves littered the siding we were on. The sky was grey and the air smelled of rain.

Los! shouted the guard.

It meant move and was a word we would hear a lot.

A man in a French forage cap and KG for Kriegsgefangener (prisoner of war) stencilled in huge white letters on the back of his greatcoat helped me off the train and into an ambulance. It was already full of bedraggled men. Some of them, like myself, had wounds swathed in dirty paper bandages.

An elderly-looking German holding a French Lebel rifle booty from 1940, when the Nazis seemed invincible was the last to get in, slamming the door behind him.

Los!

The ambulance lurched forward and gathered speed. Through two square windows in the rear door I glimpsed a few trees, the reassuring domesticity of a woman pushing a pram, a male cyclist.

Youre all lucky, announced our new guard. Youre going to an international prisoner-of-war camp. Not a concentration camp. Youre lucky youre not Jews either.

A couple of my bandaged companions nodded. The guards words relaxed us. Unless he was lying through his teeth the nagging uncertainty was over. During our passage in padlocked freight wagons, across Polands wet flatlands and into Germany, there had been time enough to ponder our fate. Would the Nazis honour the promise they had made in Warsaw to treat us as captured soldiers? It hadnt happened at the beginning of the Uprising when the SS had massacred thousands, most of them innocent civilians.

But this guard wasnt SS, just an ordinary Wehrmacht soldier, a bit too old for the uniform he was wearing, which like his captured rifle had known better days. And he seemed to want to reassure us that, as long as we behaved, we had nothing to worry about. Somebody offered him a cigarette, the Polish variety, with its dark tobacco that was all you could get during the occupation. The German nodded and stuck it into the cuff of his field-grey overcoat.