Contents

Guide

Page List

TEHRAN CHILDREN

A Holocaust Refugee Odyssey

Mikhal Dekel

For Hannan and Rivkale

Contents

M y search for the history of the Tehran Children began the day I met Salar Abdoh. Not exactly met. We had eyed each other many times before, not without curiosity, in the mailroom, in department meetings, along the corridors of the North Academic Center, the windowless, drab transplant in the grand old Gothic campus of the City College of New York, where we both taught in the English department. We might have even exchanged a few words. But the last day of the 2007 academic year was our first real conversation, the first of hundreds.

The few years that preceded my meeting with Salar were the hardest of my life. I had an infant who turned toddler but never slept, a shapeless doctoral dissertation, and many classes to teach. I had little paid help and no extended family in New York. Three afternoons a week I would drift into the North Academic Center to teach my classes and drift right back home to my son. At night I wrote my dissertation between feedings.

But one academic year passed, then another. My dissertation somehow came together. Climbing the stairs of Columbia Universitys Kent Hall on my way to the defense, I ran into my mentor, the late literary theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, who nodded at me with approval. I felt an unbelievable lightness. At the end of May, I would be marching in doctoral robe and cap at Columbia; in September, my position at City College would change from Instructor to Assistant Professor, which meant I would teach less and earn more. The April spring was gorgeous, with clear blue skies and crisp air. I taught the last class of the semester outdoors, sitting with my students on the freshly mown lawn of Shepard Hall, talking with them quietly about Melville and Freud. On the way back from class I ran into Salar, who invited me and a few others to toast the end of the school year in his office.

Salars office was lovely, with floor rugs, lamps, and kilims that covered the walls and diffused the blandness of the institutional building, and a sort of sitting area, where a few of us lounged drinking red wine and trading bits of college gossip. I remember noting Salars old-world mannerisms, a cordiality and decorum that I knew in my father and grandfather but in no one of our generation. I noted that among our colleagues, he was the most curious about Israel, where I grew up, and the least moralistic. When our conversation turned to our love of Middle Eastern seashoresSalars family had owned a house on the Caspian before the Islamic RevolutionI told him I believed my father had crossed the Caspian on his way to Iran during World War II. I knew my father had also spent time in Tehran then, that he and his sister had been among a group of refugees known as the Tehran Children, but I didnt know much more.

Salar got up, typed a few words on his keyboard, and called me to his computer screen. On the display was a February 23, 2006, issue of The Iranian, an online magazine of Iranian affairs and culture, and on its front page was an op-ed titled Revealing ErrorsIran, Jews and the Holocaust: An Answer to Mr. Black by Abbas Milani. I read the words on the screen:

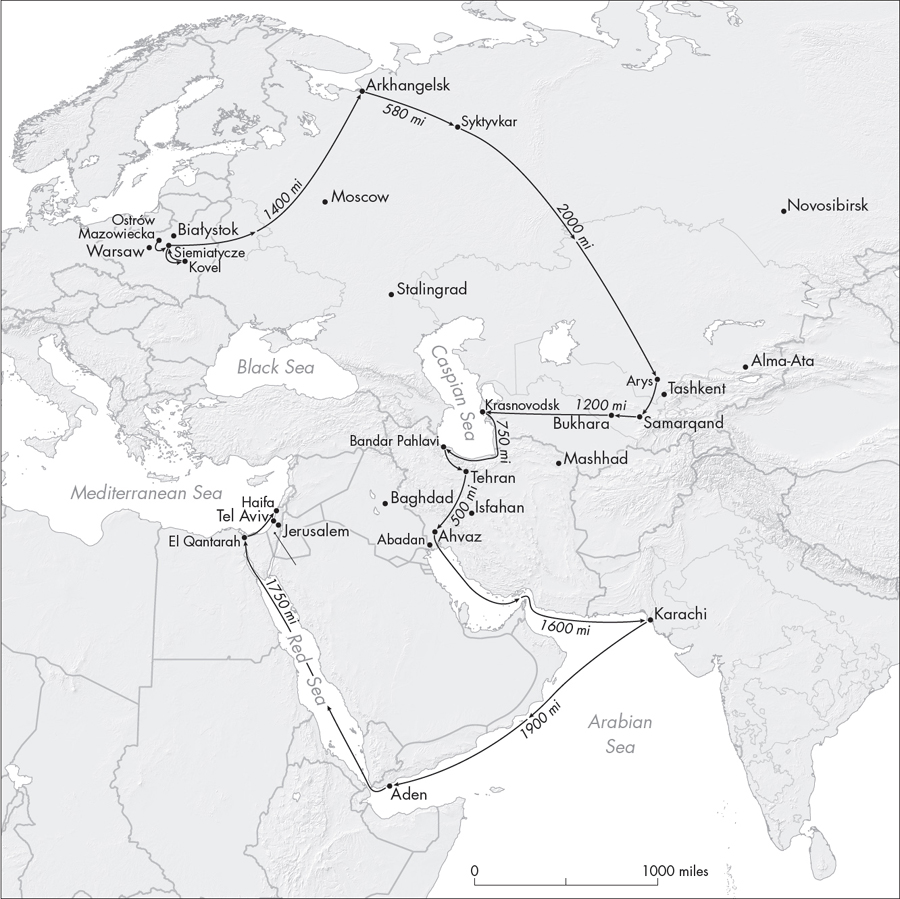

In early January of this year, a prominent American journalist published a strangely inaccurate attack on Iran, making the country complicit in the crimes of the Holocaust.... He claims that if we look at Irans Hitler-era past we will discover that Iran and Iranians were strongly connected to the Holocaust and the Hitler regime. The facts of history are just the opposite of what Mr. Black has claimed. As early signs of the murderous Final Solution became visible, the Iranian government of the time convinced the Nazi race experts in Germany that Iranian Jews had lived in Iran for over twenty-five hundred years and were fully assimilated citizens of Iran and must be afforded all the rights of such citizens. The Nazis accepted this argument and the lives of all Iranian Jews living under the Nazi yoke were saved.... Moreover... when the Nazi killing machines began their slaughter of innocent Polish Jews, 1388 Jews, including 871 children were moved to Tehran where they lived in relative safety till they moved to Israel.... History of Contemporary Iranian Jews has provided an account of what are called the Tehran Children.

I stared at the screen for a long time, then back at Salar, then sat down and read the piece more carefully. The Tehran Children, including my father Hannan (Hannania), his sister Rivka (Regina), and their cousin Noemi (Emma) were Polish-born child refugees who in 1943 came to Palestine via Iran. But until that moment I had never thought of the Tehran in that phrase as an actual place. That my father was a Tehran Child, I had always taken for granted as simply a fact about who he was, like the fact that he had straight, slightly coarse black hair that he combed back, and small, slanted blue eyes; or that he died on October 10, 1993, a year after he retired from the Israeli Air Force, where he had served for forty-eight years.

And though I am a scholar of comparative literature and trained to read across national boundaries, until that moment I could not imagine the story of the Tehran Children in any other context than the one I had internalized while growing up in Israel: as a successful rescue mission of Jewish children by the World Zionist Organization. My fathers story was an Israeli story, a part of the countrys mythology, and therefore it could not figure in the historical narrative of any other nationnot least one that had become, more recently, a political antagonist. I didnt even think of my father as a Holocaust survivor. Survivors had a muted aura of shame and anxiety in the Israel of my youth, but Tehran Children were Israelis: kibbutzniks, army generals, media personalities, industrialists. They were not Europes rejected but Israels desired, the lucky ones who had been rescued by the burgeoning Jewish state. Growing up, whenever I was asked if my father was a survivor, I would answer, No, he was not. He was a Tehran Child.

The leading scholars in my field of comparative literatureRen Wellek, Erich Auerbach, and othershad been refugees. Wellek was born in Vienna and escaped to the United States in 1939; the German born Auerbach was a refugee in Turkey and later the United States. They did not write about the refugee experience but composed, as refugees, odes to national literatures and to a unified, stable European canon. The two foremost twentieth-century historians of the nation, Eric Hobsbawm and Ernest Gellner, were also refugees. Hobsbawm was born in Alexandria, Egypt, to Jewish parents from Poland and Austria, spent his early childhood in Vienna and Berlin, fled to London in 1933, and served during the war in the British Royal Engineers and Royal Army Corps. Gellner was born in Paris, raised in Prague and escaped to St. Albans, England, in 1939. It was from the position of the mobile and the rootless, as Gellner had called it, that Auerbach wrote