Contents

About the Book

In 1998, on the lookout for adventure and willing to take a risk, John Burnett left the comforts of the mainstream and became a UN relief worker in Somalia. He was completely unprepared for the realities of working in a country without government or law, where the only authority comes from a loaded gun. Held at gunpoint by a child soldier, having to watching a baby die of malaria in his arms, the experience profoundly changed the way he saw the world.

About the Author

John Burnett is a former investigative reporter and speech-writer for Congressmen in Washington. Getting out of politics, he worked for the US Department of Interior, before spending years as writer/adventurer and considerable time as a professional seaman. He is the author of one previous book; DangerousWaters: ModernPiracyandTerrorontheHighSeas.

Where Soldiers Fear to Tread

At Work in the Fields of Anarchy

John S. Burnett

To the men and women who have fallen in the service

of helping othersquiet heroes of humanity

and

for Jacqueline

Men are not made for safe havens.

The fullness of life is in the hazards of life.

Aeschylus

Authors Note

Some of the names have been changed; while all knew I was taking notes with the purpose of possibly converting them into a book, it would be unfair to hold my colleagues responsible for what was done or said during times of such ineffable duress.

Prologue

THERE IS GOING to be a shooting here, and it is a toss-up who is going to get the boys first round. The soldier, about ten years old, is jamming the barrel of his gun hard against my drivers face, and unless the kid decides to go for me, the relief worker, my driver is going to get his head blown off.

There is something in the back of the boys eyes. Not an expression of anger or fear or hatred that might cause someone to want to kill, but the icy indifference of a childs ignorance. He has a gun. He pulls the trigger. So what? There is no dealing here.

In the few weeks of serving as a relief worker in Somalia, a nation rent by a decade of anarchy, I have come to fear children with guns. It is one thing to face an adult with a full load. But children, unlike grown-ups, do not have a personal history to balance, to offset the matter-of-fact, to work out anything rational; few adults, no matter how experienced, know how to persuade a child not to shoot. If killing is what he knowsand ten years of war is a long time to a ten-year-old carrying a gunthen there is little chance for reasoning, any one-on-one communication. Cock it. Shoot it. Next.

* * *

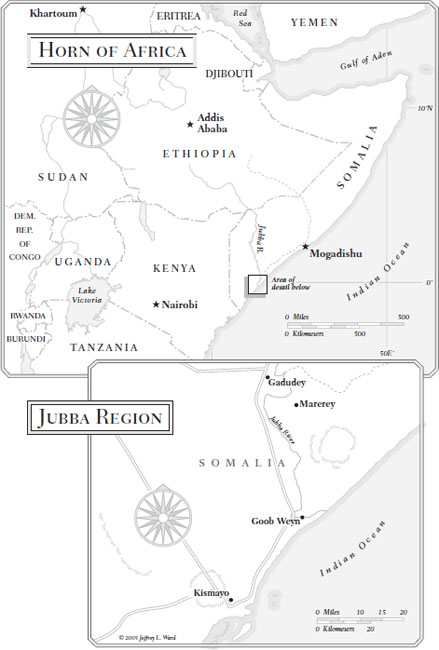

Somalia is in the throes of what is known in the jargon of humanitarian work as a complex emergency, a rather oblique way of acknowledging that we have been sent into a hostile, unstable region. Unusually heavy monsoon rains spawned by El Nio have triggered floods that have submerged most of the countrys agricultural heartland; thousands have drowned, nearly a million are homeless and starving. The United Nations, desperate and in a hurry, recruited civilians with maritime experience off the streets to drive riverboats. We were to deliver and distribute tons of medical supplies, food, clothing, and emergency shelter in a land still classified as a war zone.

When we joined this relief mission, we were told it should be safe, that we would be among a friendly people who welcomed our help, that there were no troubles in Somalia anymore. Somalis, we were informed, knew that we were sent on a mission of mercy, an attempt to keep people alive, clothed, and sheltered, and that we represented the goodwill of the developed world. Somali resentment was a thing of the past, a conflict long ago between Western peacekeepers and warlords. Yet we are discovering that in the eyes of Somalis, any international assistance, no matter how well-intentioned, is still foreign interventionwhether the international community is represented by a peacekeeper with a gun who rides herd on a relief convoy or by an unarmed aid worker delivering lifesaving medicine through the malarial and crocodile-infested floodwaters. We also were assured that we would be pulled out if the bullets ever started to fly. We took their word for it. Yet from what we have already seen, from all the missed and unanswered communications to UN headquarters, I am beginning to wonder if they remember that they sent us out here in the first place.

This past week, feuding warlords have kept our little compound under siege and held us hostage, ambushed one of our food convoys, and taken potshots at us. We try to convince ourselves that they do not want to kill us, that we are far more valuable to them alive than dead. Not as distributors of Western largesse but as hostages who would fetch enough ransom to keep a warlord in guns and bullets for months. These terrifying games are played with calculation by adults, men who know how vulnerable we are without the protection of peacekeepers, who know what a bullet can do. Our fear, however, is getting shot not by the bullet aimed at us but by the stray that had been aimed at someone else.

Then there is the child with the loaded gun.

We get accustomed to seeing proud little boys strut through the hot and dusty streets with their militia buddies toting assault rifles and grenade launchers. Here in the port city of Kismayo, there are plenty of kids and plenty of guns. Anarchy, it seems, does not soften the Somalis ability to make children.

* * *

Gritty and exhausted, I duck into the UN Land Rover for the trip back to the compound after another futile day sorting out the pieces of what is left of the bombed-out port facilities. As acting port manager, an exalted reward for being the only one available with any merchant-marine experience, it is my job to help prepare for the arrival of chartered ships bringing emergency supplies that will be delivered to the refugees Up Country. It is also my task to set up a logistics base for the small riverboats from which to mount these relief operations.

I slump between my militia guards in the back and stare out at the harbor as our old mufflerless Land Rover, hired from some local warlordno doubt booty from the last conflictchugs past rusting shipping containers on the pier. The muzzles of the guards assault rifles stick out of the car windows like deadly quills of a porcupine.

Harun, my cheerful young Somali driver, who wears an old sweat-stained New York Yankees baseball cap backward, is very suave, and he loves to chew his leaves of qat. His tough, uneven face, charred with several days growth, is belied by remarkably sympathetic eyes. His youthful swagger seems unaffected, enviably natural. He could be at home on any dark city street. He has the moves.

Harun hums along to a scratchy Arabic tune on the radio; his Kalashnikov rests against the front seat, its barrel just visible above the dashboard. His electric incense burner plugged into the cigarette lighter emits a resinous smoke.

The harbor is little more than a large open bight carved out of the coral reef. It is surrounded by white sand beaches littered with the shells of burned-out vehicles, rusting razor wire, and garbage. A causeway into the city leads from an abandoned packing plant, the shell-cratered port office headquarters, and the wharf. A helicopter landing area once used by the escaping UN military forces is painted as a faded white cross within a faded white circle on the pier.

Next page