Shake Hands With the Devil

ROMO DALLAIRE

with Jessica Dee Humphreys

THEY FIGHT LIKE

SOLDIERS

THEY DIE LIKE

CHILDREN

The Global Quest to Eradicate

the Use of Child Soldiers

The child, face and hands caked in red earth, wearing a dirty, ill-fitting bush uniform with a cross dangling from a chain around his neck, furtively aimed a machine gun at me. As bullets started to spew from the barrel, the childs eyes flared in hate. Where is that child today?

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

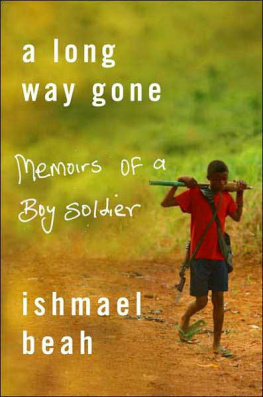

by Ishmael Beah

I AM SIMULTANEOUSLY GRATEFUL and deeply troubled to be writing a foreword for this very important work that aims to shed new light on how to end the use of children in war. Grateful that I am alive and was lucky enough to survive the civil war in my country, Sierra Leone, where I fought as a child soldier at the age of thirteen. My survival has allowed me to put a human face to this experience. I am also grateful for the fact that some measures have been taken on the international front to remove children from war, hence the possibility of my writing at this moment in time.

However, I am also deeply troubled because the usage of children in war continues and international and national mechanisms to prevent this appalling phenomenonand to hold accountable those responsible for such actsremain weak. Troubled, because what happened to my childhood and continues to destroy lives of children and their childhoods can be prevented and yet nothing concrete has been done to date.

As you read this, there is a child as young as eight, nine, ten and up to seventeen years of age in Latin America, Asia, Africa and the Middle East, who is at the brink of losing his or her childhood to war, who is starting on the path of believing that violence is an acceptable part of life. I have yet to meet a parent who would like such a life for their child. So why should the world turn a blind eye on such a paramount problem, one that will undoubtedly destroy the moral and ethical foundations of a majority of the next generation? I do not have any explanation for this blindness to the countless lives of children that have been lost, that have been amputated, the countless children who have become traumatized and lost entire families. What I do know is that there is interest in the issue and that over the years much has been learned about children who are caught up in war. As a result, a greater awareness has come about and support to create international standards to deal with this issue has grown exponentially. But this growth in awareness and the push for international legal and non-legal standards, though admirable, has yielded far too little or no impact on the ground in places of conflict and in the lives of the children who are at risk of entering conflict.

Vigorous work to bring international attention to the issue of children in conflict began in 1996, punctuated by Graa Machels report The Impact of Armed Conflict on Children. Since then, international instruments such as the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict and United Nations (UN) Security Council resolutions 1612 and 1882 (enacted to report and monitor the use of child soldiers and to hold recruiters accountable) have come into existence. In addition, there are various declarations and principles at regional and sub-regional levels to support and further expand on the existing international instruments. Unfortunately, in my view there are no workable mechanisms with direct influence in the field in place to implement these instruments. As the enforcement mechanisms continue to be ineffective, the possibility of more children finding themselves in the theatre of war increases.

As someone who knows first-hand the impact of war on children, I am constantly in search of new ideas of how to end this scourge. I strongly believe that the Child Soldiers Initiative (CSI), developed and led by Lieutenant-General the Hon. Romo A. Dallaire (Retd) in association with the Centre for Foreign Policy Studies, Dalhousie University, is an innovative project that goes at the root of the problem. It gathers all sectors and stakeholders involved in dealing with children in armed conflict to not only put an end to their use and recruitment but to eradicate the very concept of child soldier and to generate a strong global political will that is presently lacking.

It is my hope that through the pages of this remarkable book, you will discover groundbreaking thoughts on building partnerships and networks to enhance the global movement to end child soldiering; you will gain new and holistic insights on what constitutes a child soldier; you will learn more about girl soldiers, who have not been fully considered in the discussion of this issue; you will discover methods on how to influence national policies and the training of security forces; and you will find practical steps that will foster better coordination between security forces and humanitarian efforts.

I challenge you to read this important and timely work and discover that we as human beings, as nations, as the international community, have the capacity to end the use of children in war. We must not waste another minute as the task is clearly outlined in these pages.

Ishmael Beah,

author of A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier

The blue sky glittered like a new-honed knife The purity of the sky

upset me. Give me a good black storm in which the enemy is plainly

visible. I can measure its extent and prepare myself for its attack.

ANTOINE DE SAINT-EXUPRY, WIND, SAND AND STARS

IMAGINE YOURSELF ON A HILLSIDE in the chaotic throes of war, with a sea of innocents behind you whom you are tasked by duty, honour, mandate and ethics to protect. Your weapon is drawn, and you are prepared for the attack. Over the hilltop, right in front of you, comes a troop of marauding rebel soldiers with rifles and machetes. You raise your own weapon and peer through the magnifying gunsight at the leader.

Shock hits as you realize this soldier is not a man nor a professionalnot your equal in age, strength, training, understanding. This soldier is a child, in the tattered remnants of a military uniform, with dozens more children behind him.

As you stare at him, you picture yourself in a flash, aged ten, playing war games in the woods. For a split second, you are transported to the world of childhood, with its make-believe, its wonder, its potential. And in that split second, you must decide your own fate, the fate of the villagers under your protection, and of these children in front of you. Do you treat this person aiming his weapon at you as a soldier or a child? If you do nothing, dozens will be slaughtered and you put your own life at risk. If you fire to frighten or disarm, you begin a doomed and bloody shootout. Fire back to kill, as you would at an adult, and you will save a village, but at what cost?

I was a soldier. A peacekeeper. A general. Years have now passed since I stood among the corpses of a human destruction that rivalled anything Dante could have imagined. The smells, the sights, the terrible sounds of the dying in Rwanda have been damped down in my psyche to a dull roar through constant therapy and an unrelenting regimen of medication.

But no similar intervention has liberated me from the ethical dilemma that spat in my face far too often during that catastrophic period of inhumanity in Rwanda, one hundred days in 1994 that saw 800,000 human beings slaughtered in a genocide no one in the international community could muster the will to stop.

Next page