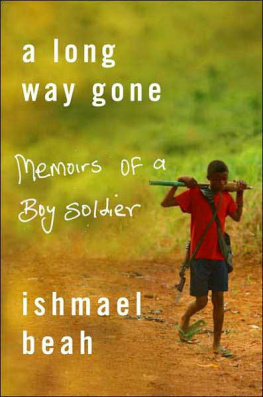

Ishmael Beah

A LONG WAY GONE

Memoirs of a Boy Soldier

To the memories of

Nya Nje, Nya Keke,

Nya Ndig-ge sia, and Kaynya.

Your spirits and presence within me

give me strength to carry on,

to all the children of Sierra Leone

who were robbed of their childhoods,

and

to the memory of Walter (Wally) Scheuer

for his generous and compassionate heart

and for teaching me the etiquette of

being a gentleman

MY HIGH SCHOOL FRIENDS have begun to suspect I havent told them the full story of my life.

Why did you leave Sierra Leone?

Because there is a war.

Did you witness some of the fighting?

Everyone in the country did.

You mean you saw people running around with guns and shooting each other?

Yes, all the time.

Cool.

I smile a little.

You should tell us about it sometime.

Yes, sometime.

THERE WERE ALL KINDS of stories told about the war that made it sound as if it was happening in a faraway and different land. It wasnt until refugees started passing through our town that we began to see that it was actually taking place in our country. Families who had walked hundreds of miles told how relatives had been killed and their houses burned. Some people felt sorry for them and offered them places to stay, but most of the refugees refused, because they said the war would eventually reach our town. The children of these families wouldnt look at us, and they jumped at the sound of chopping wood or as stones landed on the tin roofs flung by children hunting birds with slingshots. The adults among these children from the war zones would be lost in their thoughts during conversations with the elders of my town. Apart from their fatigue and malnourishment, it was evident they had seen something that plagued their minds, something that we would refuse to accept if they told us all of it. At times I thought that some of the stories the passersby told were exaggerated. The only wars I knew of were those that I had read about in books or seen in movies such as Rambo: First Blood, and the one in neighboring Liberia that I had heard about on the BBC news. My imagination at ten years old didnt have the capacity to grasp what had taken away the happiness of the refugees.

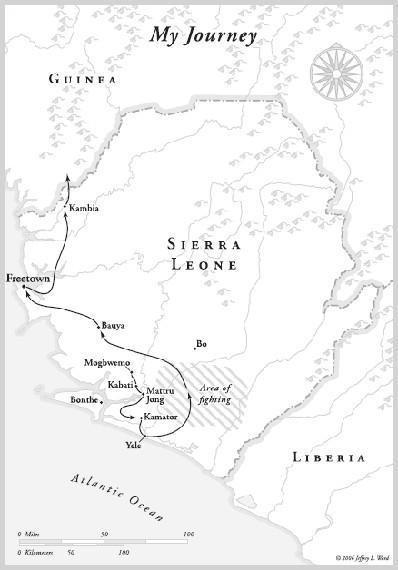

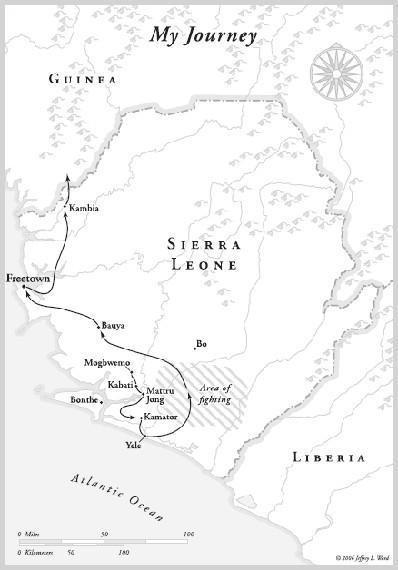

The first time that I was touched by war I was twelve. It was in January of 1993. I left home with Junior, my older brother, and our friend Talloi, both a year older than I, to go to the town of Mattru Jong, to participate in our friends talent show. Mohamed, my best friend, couldnt come because he and his father were renovating their thatched-roof kitchen that day. The four of us had started a rap and dance group when I was eight. We were first introduced to rap music during one of our visits to Mobimbi, a quarter where the foreigners who worked for the same American company as my father lived. We often went to Mobimbi to swim in a pool and watch the huge color television and the white people who crowded the visitors recreational area. One evening a music video that consisted of a bunch of young black fellows talking really fast came on the television. The four of us sat there mesmerized by the song, trying to understand what the black fellows were saying. At the end of the video, some letters came up at the bottom of the screen. They read Sugarhill Gang, Rappers Delight. Junior quickly wrote it down on a piece of paper. After that, we came to the quarters every other weekend to study that kind of music on television. We didnt know what it was called then, but I was impressed with the fact that the black fellows knew how to speak English really fast, and to the beat.

Later on, when Junior went to secondary school, he befriended some boys who taught him more about foreign music and dance. During holidays, he brought me cassettes and taught my friends and me how to dance to what we came to know as hip-hop. I loved the dance, and particularly enjoyed learning the lyrics, because they were poetic and it improved my vocabulary. One afternoon, Father came home while Junior, Mohamed, Talloi, and I were learning the verse of I Know You Got Soul by Eric B. & Rakim. He stood by the door of our clay brick and tin roof house laughing and then asked, Can you even understand what you are saying? He left before Junior could answer. He sat in a hammock under the shade of the mango, guava, and orange trees and tuned his radio to the BBC news.

Now, this is good English, the kind that you should be listening to, he shouted from the yard.

While Father listened to the news, Junior taught us how to move our feet to the beat. We alternately moved our right and then our left feet to the front and back, and simultaneously did the same with our arms, shaking our upper bodies and heads. This move is called the running man, Junior said. Afterward, we would practice miming the rap songs we had memorized. Before we parted to carry out our various evening chores of fetching water and cleaning lamps, we would say Peace, son or Im out, phrases we had picked up from the rap lyrics. Outside, the evening music of birds and crickets would commence.

On the morning that we left for Mattru Jong, we loaded our backpacks with notebooks of lyrics we were working on and stuffed our pockets with cassettes of rap albums. In those days we wore baggy jeans, and underneath them we had soccer shorts and sweatpants for dancing. Under our long-sleeved shirts we had sleeveless undershirts, T-shirts, and soccer jerseys. We wore three pairs of socks that we pulled down and folded to make our crapes*{Sneakers.} look puffy. When it got too hot in the day, we took some of the clothes off and carried them on our shoulders. They were fashionable, and we had no idea that this unusual way of dressing was going to benefit us. Since we intended to return the next day, we didnt say goodbye or tell anyone where we were going. We didnt know that we were leaving home, never to return.

To save money, we decided to walk the sixteen miles to Mattru Jong. It was a beautiful summer day, the sun wasnt too hot, and the walk didnt feel long either, as we chatted about all kinds of things, mocked and chased each other. We carried slingshots that we used to stone birds and chase the monkeys that tried to cross the main dirt road. We stopped at several rivers to swim. At one river that had a bridge across it, we heard a passenger vehicle in the distance and decided to get out of the water and see if we could catch a free ride. I got out before Junior and Talloi, and ran across the bridge with their clothes. They thought they could catch up with me before the vehicle reached the bridge, but upon realizing that it was impossible, they started running back to the river, and just when they were in the middle of the bridge, the vehicle caught up to them. The girls in the truck laughed and the driver tapped his horn. It was funny, and for the rest of the trip they tried to get me back for what I had done, but they failed.

We arrived at Kabati, my grandmothers village, around two in the afternoon. Mamie Kpana was the name that my grandmother was known by. She was tall and her perfectly long face complemented her beautiful cheekbones and big brown eyes. She always stood with her hands either on her hips or on her head. By looking at her, I could see where my mother had gotten her beautiful dark skin, extremely white teeth, and the translucent creases on her neck. My grandfather or kamor