Contents

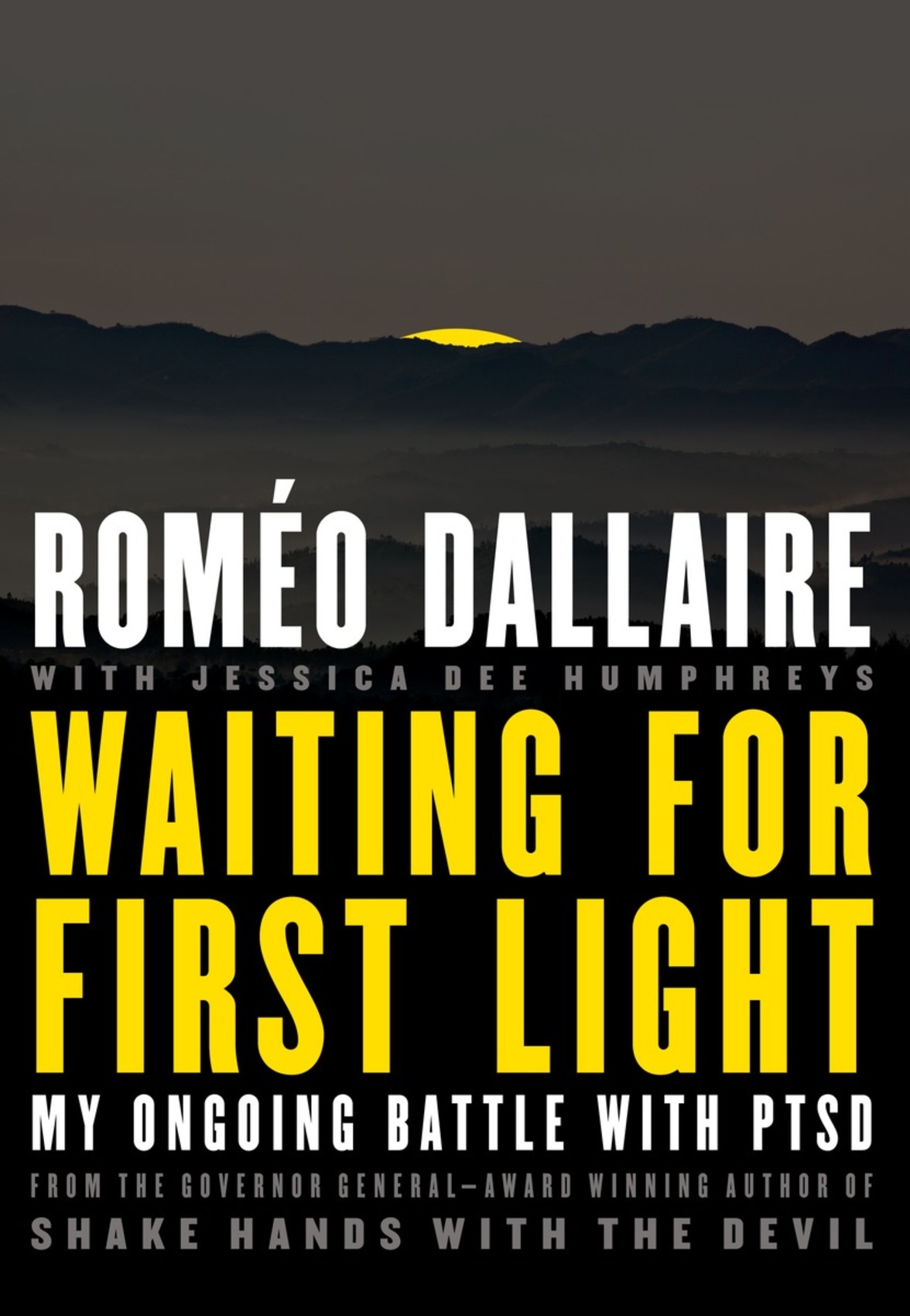

ALSO BY ROMO DALLAIRE

Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda

They Fight Like Soldiers, They Die Like Children:

The Global Quest to Eradicate the Use of Child Soldiers

PUBLISHED BY RANDOM HOUSE CANADA

Copyright 2016 Romo A. Dallaire, LGen (ret) Inc.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2016 by Random House Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Distributed in Canada and the United States of America by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

Random House Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Dallaire, Romo A., author

Waiting for first light : my ongoing battle with PTSD / Romeo Dallaire.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-345-81443-2

eBook ISBN 978-0-345-81445-6

1. Dallaire, Romo A. 2. Dallaire, Romo A.Mental health.

3. Post-traumatic stress disorderPatientsCanadaBiography.

I. Title.

RC552.P67D35 2016616.85210092C2016-903976-5

Ebook design adapted from book design by Five Seventeen

Cover photo: Guenter Guni/E+/Getty Images

v4.1

a

For Willem, Flower and Guy,

and the generations to follow.

And for my wife, Beth.

Forthwith this frame of mine was wrenched

With a woeful agony,

Which forced me to begin my tale;

And then it left me free.

Since then, at an uncertain hour,

That agony returns:

And till my ghastly tale is told,

This heart within me burns.

SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE,

THE RIME OF THE ANCIENT MARINER

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Esteemed General,

After reading your memoir of the holocaust that engulfed you in Rwanda in 1994, it is striking that your anguish was so akin to that of S. T. Coleridges Ancient Mariner.After your premonition went unheeded, you were virtually abandoned by all but for a small band of brave soldiers. Thus you were left powerless to halt the horror of the slaughter of innocents by the gnocidaires and, like the Mariner, as a commander you felt steeped in guilt. Also like the Mariner you endure the anguish of life-in-death. But you ultimately mustered the courage and resilience to subdue it, then devoted yourself to providing succour to the victims of war.I offer you the poem as a token of my respect and admiration.IR

A FEW YEARS AGO , I received a package in the mail from the deputy head of UN Peacekeeping Operations during the Rwandan genocide, Iqbal Riza. An unfailingly sensitive gentleman, Mr. Riza had sent me a large, illustrated edition of Coleridges Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

As I turned the pages, I became immersed in the Ancient Mariners retelling of his doomed mission. I was struck by so many similarities between his story and my own: the burden of his command, his witness of unadulterated horror, his impotence, his guilt, his resolve. And his unconscious imperative, that maddening drive to educate the world about what he had experienced.

To summarize the story (in case high-school English class was as long ago for you as it is for me): an old man pulls a wedding guest away from the nuptial festivities and forces him to listen to his story. The old man had commanded a crew on a voyage of exploration, aboard a ship bound for parts unknown. When the weather turned rough, the ship was lost, and of all the crew, only their helpless captain survived. Water, water, everywhere/Nor any drop to drink. The Ancient Mariner remained forever tormented by guilt: guilt at being alive when so many others died; guilt at failing in his command, failing to keep the others safe, failing his mission; guilt over his part in the tragedy, for which he is forever blamed.

The horrifying deaths he witnessed were senseless, and void of meaning, as was his remaining alivea roll of the dice. But it is human nature to seek understanding through cause and effect, and so the Mariner relives again and again the moments before the horror, trying to understand what he could have done to prevent it. Rightly or wrongly, he blames himself for bringing on the horror by shooting an albatross.

The Mariner is burdened by both guilt and responsibility. The guiltrepresented by the albatross hung around his neckis relieved, at least a little, when he rediscovers beauty in place of his revulsion. However, his responsibilityimposed on him by a character called Life-in-Deathnever leaves him: the eternal responsibility to tell the tale, since he was the commander, and the survivor.

I, too, was a commander who set out on what I thought was an exciting adventure, only to bear witness to the most terrible horrors on earth. I, too, was responsible for the mission, and therefore bear the responsibilities for the deaths. I, too, face blamefrom others and from myselffor not preventing the atrocities. I, too, live Life-in-Death.

Wethe Ancient Mariner and Iboth became mired in guilt, both wanted so much to die but could not, and both eventually chose to take meaningful action. We persevere in our resolve to ensure the story is never forgotten, and that those who died did not do so in vain.

When each of us told our story in its entirety for the first time, we began a cycle that will continue throughout our lives: reliving the pain by telling the story, an action that attenuates the pain, which then returns upon the telling and must be relived to be relieved.

Teaching others by sharing our stories relieves us, temporarily, of our suffering. Of course, full recovery from a trauma this great is impossible and lasting serenity will forever evade us. The Mariner and I lived, when so many beautiful, innocent people died. The pain of that will never cease, and so we both devote our lives to sharing the story with others who might understand and learn. In this way, we attempt to build an ethical legacy, creating sadder but wiser humans.

I have already told my story of the Rwandan genocide. In Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda, and in speeches and presentations before and since that book was published, I explained what I saw. What I did. What I was unable to do. While I have not been silent about the injury I sustained in Rwanda, I have kept mostly private the effects of that injury on my mind, my body, my soul. Until now.