Also By Joel Engel

L.A. 56: A Devil in the City of Angels

The Oldest Rookie

By Duty Bound: Survival and Redemption in a Time of War

What Would Martin Say

Rod Serling: The Dreams and Nightmares of Life in the Twilight Zone

(reissued as Last Stop, The Twilight Zone)

Screenwriters on Screenwriting

Oscar-Winning Screenwriters on Screenwriting

By George: The Autobiography of George Foreman

Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man Behind Star Trek

Addicted

2018 by Joel Engel

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Encounter Books, 900 Broadway, Suite 601, New York, New York, 10003.

First American edition published in 2018 by Encounter Books, an activity of Encounter for Culture and Education, Inc., a nonprofit, tax exempt corporation.

Encounter Books website address: www.encounterbooks.com

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Jacket images: background Stuart McCall/Photographers Choice/Getty Images; sparks and burnt texture photka/Shutterstock.com, Bernatskaya Oxana/Shutterstock.com, and Angelina Babii/Shutterstock.com; seal Ilyashenko Oleksiy/Shutterstock.com

FIRST AMERICAN EDITION

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Engel, Joel, 1952-author.

Title: Scorched worth: a true story of destruction, deceit, and government corruption / by Joel Engel.

Description: New York: Encounter Books, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017039033 (print) | LCCN 2017040455 (ebook) | ISBN 9781594039829 (Ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: United States. Department of JusticeCorrupt practices. | Justice, Administration ofCorrupt practicesUnited States. | Misconduct in officeUnited States. | Political corruptionUnited States.

Classification: LCC KF5107 (ebook) | LCC KF5107 .E54 2018 (print) | DDC 347.73dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017039033

To every law enforcement officer, investigator, and prosecutor motivated by justice. That you are the overwhelming majority is a great comfort. That there is a small minority motivated by something else is cause for eternal vigilance.

The United States wins its point whenever justice is done its citizens in the courts.

INSCRIPTION ON THE WALLS OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

Contents

Table of Contents

Guide

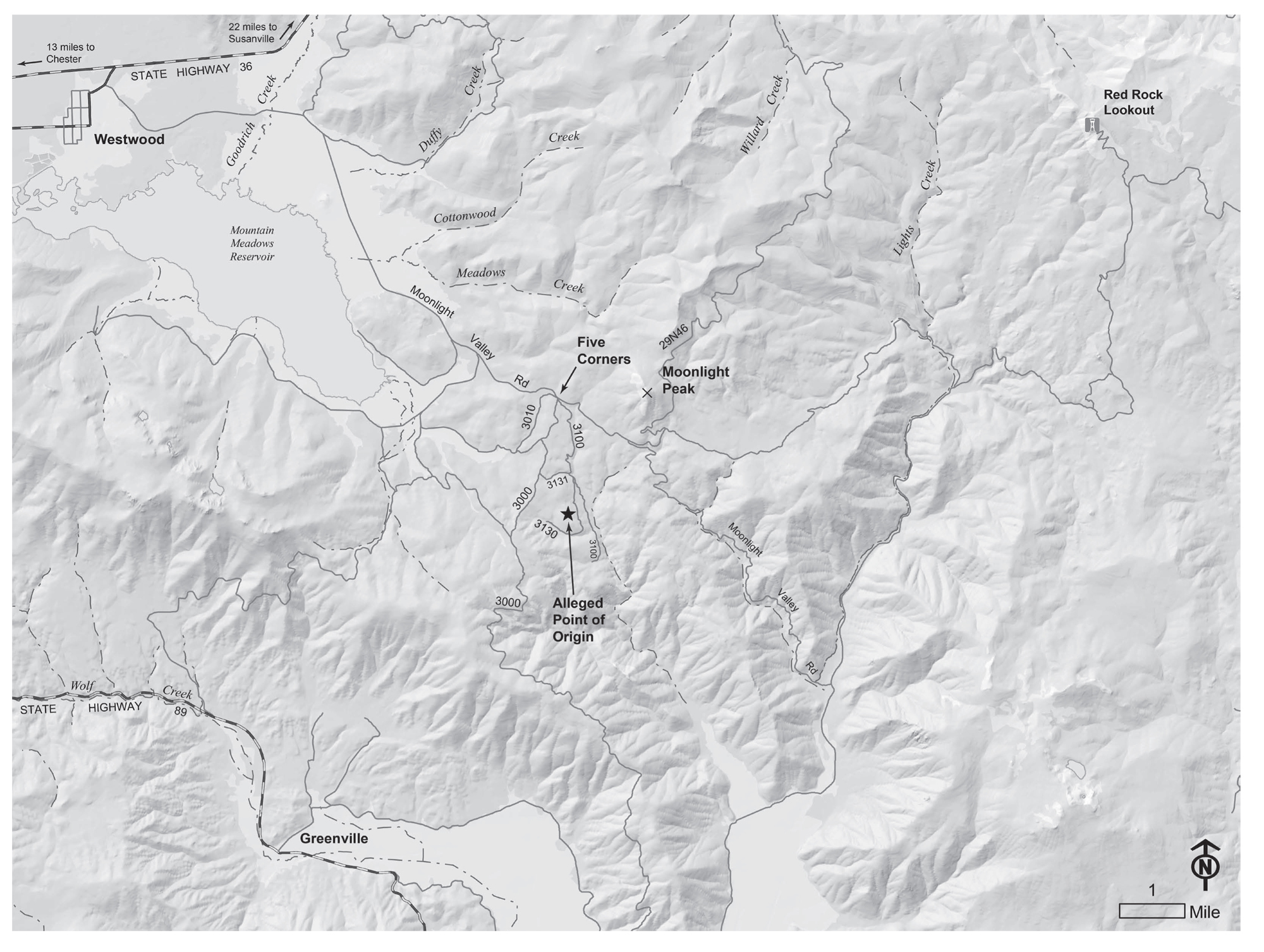

T he Moonlight Fire, as it would come to be called, began September 3, 2007Labor Daytwo and a quarter miles from Moonlight Peak in the Plumas National Forest of Californias eastern Sierra Nevada, southeast of the town of Westwood and northeast of the town of Greenville, as the fires official report later put it. Though the precise time the fire broke out at this mile-high elevation on a hot, windy day would become the subject of much serious debate, with significant ramifications, it was reported at 2:25 P.M. by the fire prevention technician from a truck parked below the Moonlight Peak lookout tower.

The apparent point of origin was not on land owned by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) but on adjacent private landsreported as an east-facing slope in the Cooks Creek drainage areafor which the owners had sold temporary logging rights to Sierra Pacific Industries (SPI), one of the countrys largest lumber companies. In turn, SPI had contracted with a long-established mom-and-pop company, Howells Forest Harvesting, to cut the timber and manage the harvest before snows began in November.

Firefighters arrived quickly and fire suppression aircraft began dropping borate, a retardant, just before 3:00 P.M. Southerly winds pushed the fire north-northeast, angling down-slope in this mountainous area covered with tinder-dry terrain that hadnt burned or been thinned by man for decades. It advanced as a crowning fire, meaning that the tops of the conifer trees were so close together that they easily ignited, sometimes independently of what the fire was doing on the ground.

By nine oclock that night, when darkness halted flights, only about 250 acres had burned, and there was hope a complete conflagration might be averted. But in the morning, a cold front brought erratic winds and downdrafts from thunder-cloud cells, making any effective containment measures impossible. By noon nearly two thousand acres had burned or were burning, and for several hours that afternoon the firefighters had to cease their work because the winds and meteorological conditions were too unpredictable. That night the firefighters were prevented from going out by lightning strikes, some of which may have sparked more blazes. Winds reached twenty-five miles an hour.

The third morning brought more of the same, then worse. Winds from the northeast pushed the fire toward populated areas in Indian Valley, where rugged terrain, wind gusts, and variable meteorology hampered all firefighting. By late afternoon on September 5, the blaze had burned more than twenty-two thousand acres.

Another six thousand acres went up the next day when firefighters were prevented from accessing huge portions of the steep perimeter. From there the fire burned uninterrupted from Indicator Peak in the north to Rattlesnake Peak in the south; and on the following day it began pushing eastward into areas that had been recently thinned, where the fuel load was less dense.

On September 8 the fire detoured in almost a circle around the firefighters, rendering them impotent, though fortunately unharmed.

By afternoon, wind speeds moved into the high teens, but there was good news: except for years worth of pine needles on the forest floor, the fuel load consisted of fewer trees with greater spacing between them, making the fire less hot and angry. The bad news was that spot fires began breaking out, some of them with the potential to become large enough to earn their own names.

The seventh day brought weather conditions that allowed firefighters to build a fire line up Wildcat Ridge, and the intentional burnout continued downhill until the fire line stopped the fires eastward progression. There was nothing now left to burn in front of it. The fire had gotten as big as it was going to get, spreading from Taylor Lake in the south nearly to the Diamond Mountain Motorway in the north.