For Lorrie Neill Kamensky,

and in memory of Donald Louis Kamensky

Great Revolutions in Government, are generally attended with great Calamity to Individuals.

Elisha Hutchinson to Margaret Hutchinson, January 1776

Many of the Shades of the Portraits, both of Persons & Times, I confess are very dark: that is not my Fault. My Business was to draw true Portraits.

Peter Oliver , Origin and Progress of the American Rebellion, 1781

The same truth that guides the pen of the historian should govern the pencil of the artist.

Benjamin West to John Galt, ca. 1816

Contents

Contents

A R EVOLUTION IN C OLOR

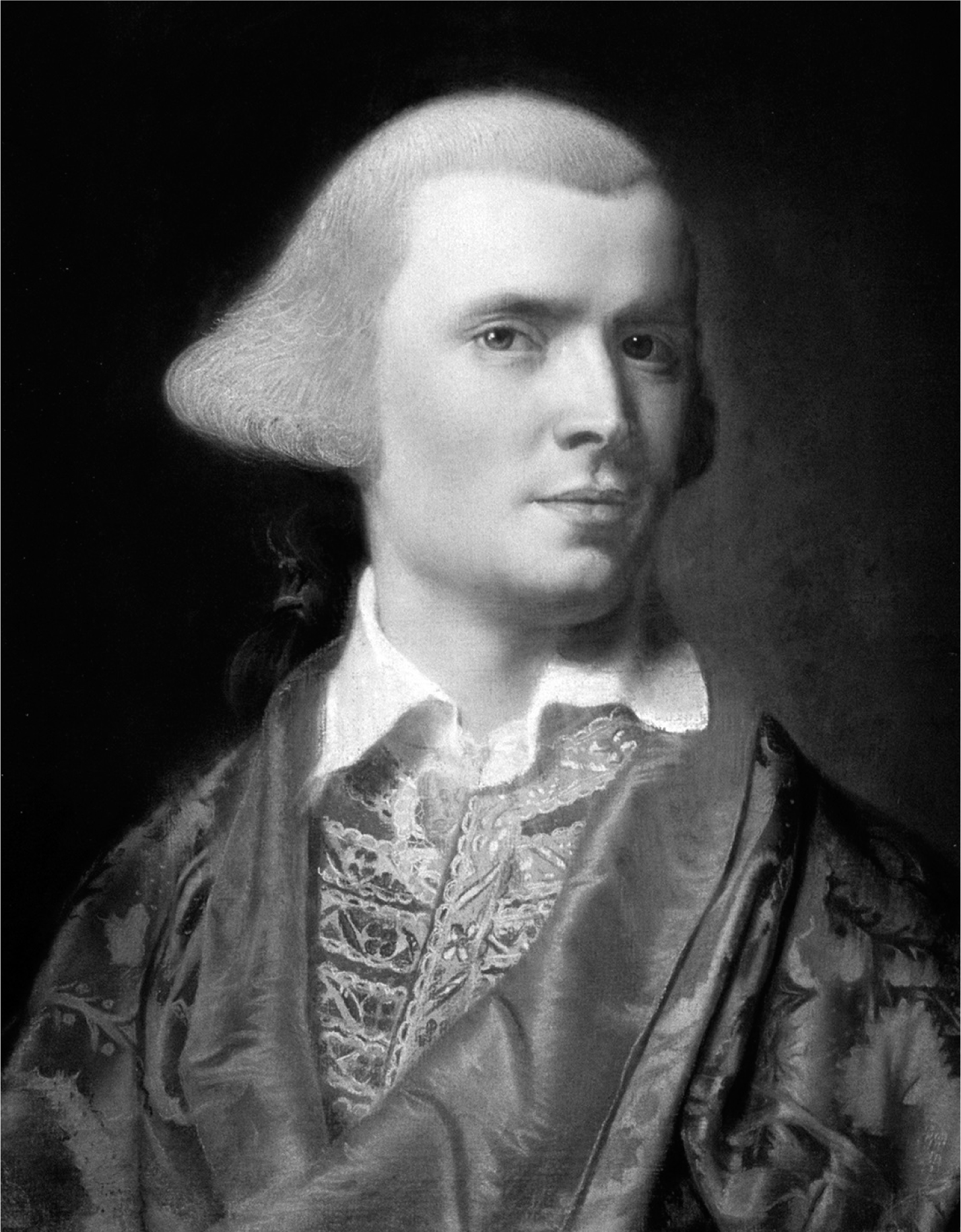

W HEN YOU WALK through the heavy glass doors of the Americas wing in Bostons Museum of Fine Arts, you come face to face with the men and women who made the American Revolution. Paul Revere greets you, head on, just inside the entrance. His iconic likenessunwigged, shirtsleeved, silver teapot in handhangs low enough that his big brown cow eyes meet yours with neither modesty nor condescension. Reveres is the honest, direct gaze of an honest, direct man: an American gaze. Vitrines holding examples of the silversmiths craft surround the portrait of the self-made maker. His famous Liberty Bowl stands on a platform just in front of it, like a chalice proffered by a preacher. In the 1950s, the churchiness of the presentation was franker; the portrait and the bowl were placed upon a pedestal with a couple of steps before it, suitable for genuflecting, flanked by American and Massachusetts flags. But even today, in a new and less earnest century, Paul Revere forms the center panel of an American altarpiece.

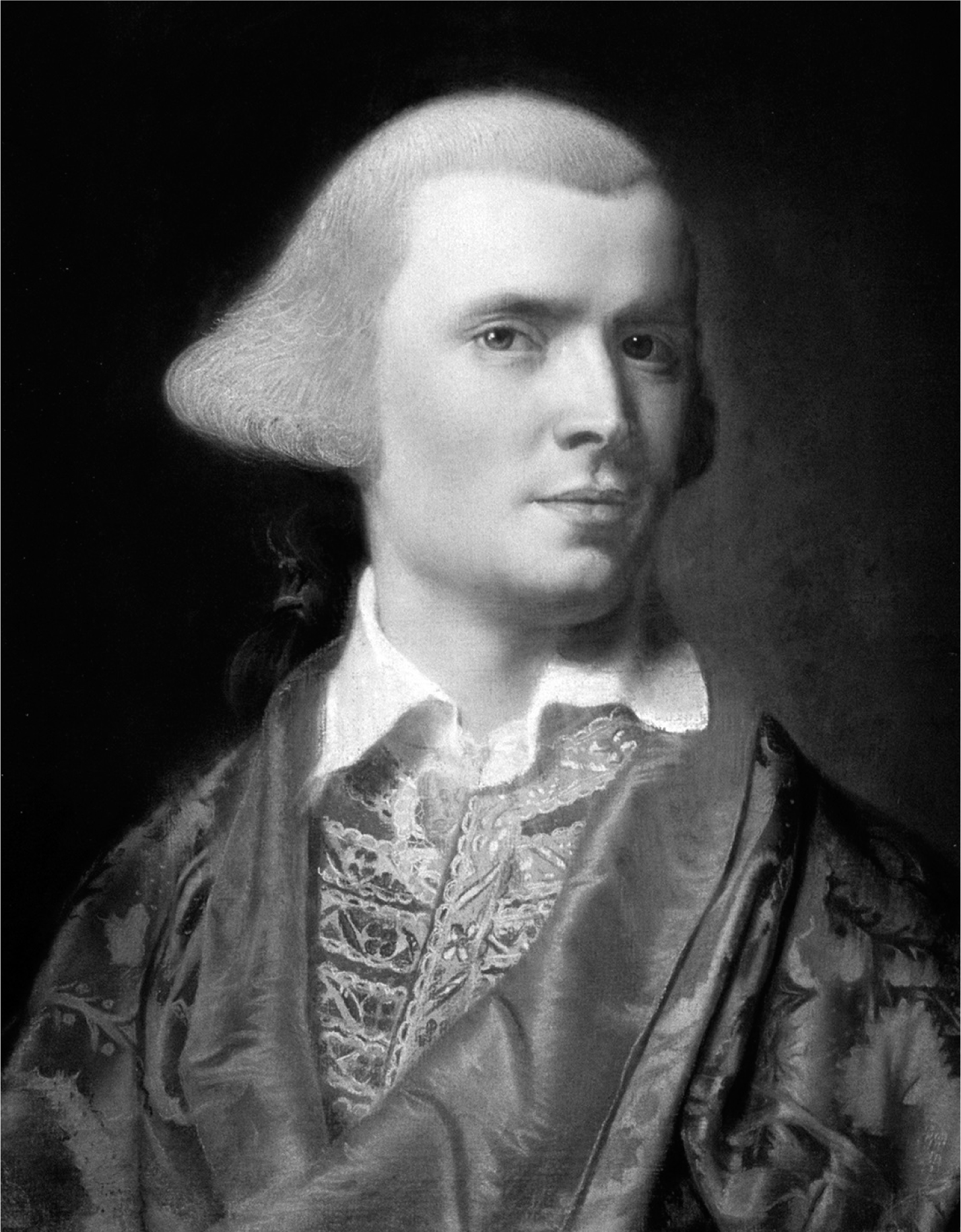

Behind Revere, on the left, hang a quartet of his fellow revolutionaries. John Hancock, the stalwart merchant, sits at his desk, reckoning, the quill that will ink his bold signature on the Declaration of Independence poised in his right hand. Samuel Adamsthe maltsters son turned politicianstands in a homespun crimson suit, drawn up to his full, modest height, eyes alight with patriotic zeal. Dr. Joseph Warren, the physician, pores over a set of anatomical drawings that seem to prefigure his death and resurrection as the martyr of Bunker Hill. Mercy Otis Warren, the sister of one liberty man and the wife of another, appears lost in thought as she stands before a burbling fountain, displaying the contemplative bent of the intellectual who will write the Revolutions first major history. The portraits were painted separately, in the 1760s and early 1770s, tumultuous years in the world beyond their gilded frames. They were meant for separate fates, in firelit parlors in middling homes, in a bustling entrept at the edge of an empire. Viewed together centuries later, in the chilly splendor of a great museum, through the glaring light of hindsight, they become a patriotic pantheon: American originals, painted by another of their breed. The labels identify the artist as John Singleton Copley, American, 17381815.

The MFA owns the largest collection of Copleys work in the world: scores of paintings spread across four galleries and myriad works on paper tucked away in the department of prints and drawings, where they can be viewed by appointment, under low light. But though Copleys legacy is more vivid in Boston than in most other places, just about any major museum in the United States will tell you a version of the same story. At the Met in New York or the Art Institute of Chicago, at the National Gallery in Washington or the De Young Museum in San Francisco, in Detroit and Toledo and Lawrence, Kansas, and Crystal Bridges, Arkansas, and on around the vast continental nation that Copley never imagined, his work is classed as American art, with labels that add greater and lesser degrees of mystery: American, active in Britain, American, died in London. Whatever the label, Copleys brush is pressed into much the same service: a conjurers work, creating our minds eye picture of the nascent American republic, of which he emerges, on those walls, as court painter.

Nothing would have surprised Copley more.

A cautious man in a rash age, John Singleton Copley feared the onrush of the colonial rebellion against Great Britain. Like many people of his place and time, he called the rebels revolution a civil war. And like many people who had lived through civil wars before him, and who have endured them since, he thought the safest side was no side at all. Copley painted John Hancock, whom he knew well and grew to despise. But by the time Hancock signed the Declaration, the painter was long gone from the country that document called into being. In the spring of 1774, during the brief interval between Bostons tea party and the outbreak of fighting in Lexington and Concord, Copley sailed to London, capital of the only nation he had ever known, leaving behind the second-tier British port city in which he had spent nearly four decades. John Singleton Copley had lived half his life in Britains American provinces. He would never set foot in the United States.

British museums, which own the greatest of his works, classify him differently. John Singleton Copley, R.A. British School, runs the text inscribed on the frame of The Death of Major Peirson , my very favorite of all his paintings, which hangs in the Tate, hard by the Thames. The heroic canvas depicts a passage in Britains American War that falls outside the standard narrative of the American Revolution: a battle that took place in an obscure corner of Europe, that featured no North American combatants, and that ended in British victory.

To explore Copleys American Revolution is to treat that war, and its world, with fresh eyes. In the United States, where the War of Independence functions as a national origins storya foundingwe tend toward histories peopled by Patriots and Tories, victors and villains, right and wrong. Such tales, for all their drama, are ultimately flat: morality plays etched in black and white, as if by engravers who have only ink and paper to depict all the shades of a subject. But like the paintings Copley produced so painstakingly, the revolutionary world was awash in an almost infinite spectrum of color. Allegiance came in many shades. Some pigments were durable, others fugitive and shifting. The age of revolutions takes on a prismatic quality when we try to view it through Copleys slate-colored eyes, eyes that saw deeply, and revealed many truths, not all of which we now hold to be self-evident.

My title also refers to Copleys work, which began, in his tender years, as a trade. As he grew in both mastery and drive, it became a calling. As a painter of portraits and, once he escaped the confines of Boston, of the more elevated genres of history, religious art, and classical allegory, Copley worked in the upper echelons of the color trades, which included everyone from the farmers who grew the madder root from which the days most popular bricky reds were made, to the collectors of burnt ivory that produced the richest blacks, to the merchants who trafficked in powdered pigments from around the globe and the shopkeepers who sold them at retail, to the many kinds of painters who worked with those stuffs: housepainters and sign painters and clock painters and wallpaper screeners, and on up the ladder of occupations to the painters of landscapes, human faces, and the higher reaches of Art.

Next page

Contents

Contents