SETH: CONVERSATIONS

Conversations with Comic Artists M. Thomas Inge, General Editor

Seth: Conversations

Edited by Eric Hoffman and Dominick Grace

Works by Seth

Palookaville, 22 issues (19902014)

Its a Good Life, If You Dont Weaken (1996)

Vernacular Drawings (2001)

Clyde Fans, Book One (2004)

Bannock, Beans and Black Tea: Memories of a Prince Edward Island Childhood in the Great Depression (2004) (with John Gallant)

Wimbledon Green: The Greatest Comic Book Collector in the World (2005)

Forty Cartoon Books of Interest (2006)

George Sprott (18941975) (2009)

The Great Northern Brotherhood of Canadian Cartoonists (2011)

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2015 by University Press of Mississippi

Copyright cover painting by Seth/Gregory Gallant

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2015

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Seth, 1962

[Interviews. Selections]

Seth : conversations / edited by Eric Hoffman and Dominick Grace.

pages cm. (Conversations with comic artists series)

Collection of interviews originally published in various sources.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-62846-130-5 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-62846-131-2 (ebook) 1. Seth, 1962Interviews. 2. CartoonistsCanadaInterviews. I. Hoffman, Eric, 1976 editor. II. Grace, Dominick, 1963 editor. III. Title.

PN6733.S48Z46 2015

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

CONTENTS

Michael Strafford / 1985

Dylan Williams / 1995

Bryan Miller / 2004

Dave Sim / 2005

Gerald Hannon / 2006

Rebecca Bengal / 2006

Thom Ernst / 2009

Tom Spurgeon /2009

Eric Hoffman and Dominick Grace / 2013

INTRODUCTION

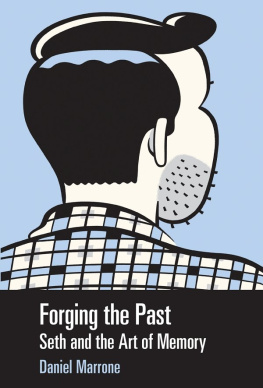

Seth, born Gregory Gallant in Canada in 1962, is one of the most significant artists to emerge in the alternative comics boom of the 1980s, as a cartoonist, designer, and comics historian. As we have discussed elsewhere (see the introduction to Chester Brown: Conversations [2013]), the 1980s was a fascinating transitional period for the comics industry. Most mainstream (i.e. superhero-focused) publishers had died out, leaving Marvel and DC as the primary forces on the newsstands. Companies providing some sort of alternative to the hegemonic superhero worlde.g. Warren, or the underground publisherswere also shrinking or dying out. However, several factors conspired to create an environment receptive to new developments in comics. One of these was the development in the 1970s of the direct comics market, whereby comics stores could order books directly from distributors on a nonreturnable basis (in contrast to the longstanding returnable distribution system). This was a key factor in the proliferation of comics specialty stores, which could get books more cheaply and easily via the direct market than they could under the old newspaper and magazine distribution system. Coupled with this development was the growth of comic book conventions again, a phenomenon that began in the early 1970s and flourished by the end of the decade.

These twin forces provided not only a venue for mainstream books to be more widely disseminated but also the development of a growing market of readers interested in comics as a legitimate cultural medium. Instead of finding their comic fixes haphazardly in convenience stores or on newsstands, comics fans could now, in many cities, find them in shops that specialized in comics. These shops provided a reliable source for new books as well as an increasing stock of back issues. Readers could now easily find the books they wantedand many other books of which they had never heard before. The creation of this market benefited more than just the established publishersthough it came too late to save many stalwarts, such as Charlton, Gold Key, Dell, and othersand it remains a fascinating period in comics history, providing a pathway for new publishers to get their books distributed and noticed. The alternative/ground-level comics movement was born.

Charles Hatfield discusses the birth of the alternative comics movement in Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature, noting that the term ground-level was applied to such books because such they attempted to reconcile underground and mainstream attitudes (26), for example by wedding the fantasy tropes of the mainstream with the look and sensibility of the undergroundblack and white art, more explicit sexual and violent content, and, most importantly, perhaps, a more idiosyncratic and personal perspective. The first wave of such books includes those with essentially mainstream narrative drivesthe fantasy series The First Kingdom (19741977) by Jack Katz, for exampleand in many cases the creative powers of mainstream talent seeking slightly more creative freedom. The second wave saw a more coherent and professional approach in the emergence of new companies (e.g. Pacific, which provided a home for Jack Kirbys later superhero work, or Eclipse, which published many more graphic but still essentially mainstream titles). The third wave of the early to mid-1980s saw a ground-level comics world in many respects still heavily invested in mainstream sensibilities (one of the key books of this period is Howard Chaykins American Flagg! [19831988] for First Comics, a visually dense, relatively sophisticated satirical science fiction dystopian narrative that is nevertheless firmly rooted in mainstream genre tropes), yet which also saw the emergence of artistsand publisherswith more ideologically driven commitments to significant alternatives to the mainstream, and a far more diverse and eclectic approach to style and narrative. This period also saw the proliferation of artists interested in taking comics beyond the limits of mainstream tropes and of publishers interested not merely in providing somewhat more adult and sophisticated variations on superhero power fantasies but also in opening up comics as a medium capable of exploring any subject matter. If publishers such as Pacific, Eclipse, First, or Vortex closely approximate the mainstream aesthetic, ones like Raw (founded by Art Spiegelman and Franoise Mouly in 1980 in the wake of the demise of the underground comic Arcade as a new forum for avant-garde comics), Fantagraphics (founded in 1976 and initially the publisher of The Comics Journal [1977present], this publisher put its aesthetic theories into practice when it began publishing comics in 1981) and Drawn & Quarterly (founded in 1990 by Chris Oliveros, on the model of Speigelman and Moulys Raw magazine [19801991], to publish art comics) set out to redefine what comics could be.

Seth, along with several other major comics talents, emerged in the 1980s and benefited from this fertile environment. Like many of his contemporaries, Seth was influenced by both mainstream comics and underground comix, as well as by the DIY aesthetic of the punk and new wave movements. Indeed, he traces his pseudonym, with some embarrassment, to his involvement with youth culture: I was involved with the punk scene and the nightclub scene and I got heavily involved in creating a whole new persona for myself and eventually that also involved coming up with a new name, he tells Thom Ernst in one of the interviews collected here. He notes elsewhere, I wanted a scary pseudonym and I made [a] list of names. I picked Seth. I shudder to imagine what else was on that list. Thank God that Seth is, at least, a real name. It could have been much worse (Stukavsky n.p.).

Next page