CONTENTS

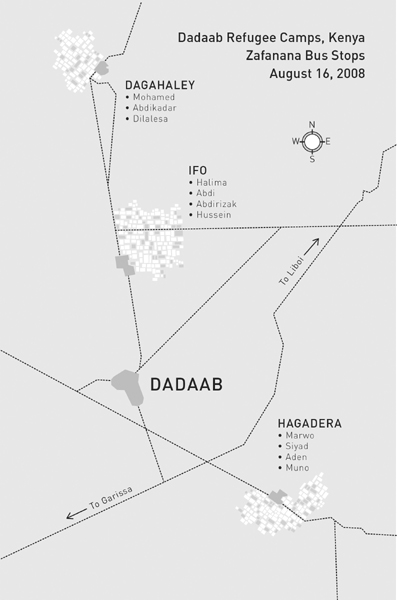

Map of Dadaab Refugee Camps, Kenya

Zafanana Bus Stops: August 16, 2008

INTRODUCTION

Becoming Universal

I N THE FALL OF 2009, as I was writing this book, my daughter left home and moved to a city across the country. She had finished university and was trying to figure out what she was going to do with her life. It was a good time for her to leave homethere was nothing unnatural about her departure. And yet for her and for me it was a traumatic event. The emotions of the departure, and of the days before and after it, made me feel more deeply for the parents and the young people you are about to meet in this story.

My daughter moved away from home to a city in her own country, and she understood that if things didnt work out for her there, she could always come back home. Even so, on her second day away from home, she called to say she didnt know where she belonged. The mothers and fathers of the young people in this story could hardly imagine the strange world their children were entering. Many of them feared that Western culture might change their children beyond recognition. And yet they let them go because it was the only choice that offered any hope for the future. Without the safety net of family, the students in this story left their homes in the refugee camps of Dadaab, Kenya. They had a one-way ticket to Canada and the knowledge that this was their best shot at a productive adulthood.

It may seem self-indulgent to compare the journey of an educated middle-class Canadian to students who grew up as refugees and came alone to a completely unknown Western country. But we have all had departures that tore at us, and I hope that those reading this story will draw on their own memories to understand the dislocation and the heartache and the challenges to their identities that these young people faced. It is too easy to think of refugees as a block, as something other, even as something to be feared. It is harder to take the time to realize that their individual stories have elements in common with our own. Refugees too often invite compassion fatigue instead of simply compassion.

Displacement is part of the human condition. Over the centuries, people have moved to avoid floods, wars and famine. In its annual report on global trends, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, UNHCR, estimated there were 42 million forcibly displaced people worldwide at the end of 2008. Of those, 15.2 million were refugees in asylum countries, 10.5 million of them under the care of UNHCR. More than half of those under UNHCR care had been living in exile for more than five years with no solution in sight in what humanitarians call protracted refugee situations.

Forty-two million. Its not a number easy to imagine. Forty-two million. It is not a number that suggests that solutions are around the corner. Forty-two million. It is a number hard to connect to individuals with sorrows, regrets, fears and despair, or with lives of marriages, births, songs and poetry.

Displacement is also a big part of the Canadian story. We are a nation of people who, for the most part, have come from somewhere else and, usually, because we had to. There were the Irish who faced death or Canada after the potato famine of the 1840s; the Doukhobors and the Jews who escaped pogroms in czarist Russia; the Ukrainians who settled in the prairies before the First World War; the Hungarians and Czechoslovakians who ran from Soviet oppression in the 50s and 60s; the boat people fleeing from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos in the late 70s.

The blemishes in our record of accepting displaced people are part of our countrys shame. Theres the Komagatu Maru incident of 1914, when authorities in Vancouver would not allow steamboat passengers from India to disembark on Canadian soil, and the horror of the MS St. Louis in 1939, when Canada refused to accept nine hundred Jews escaping Nazi Germany. Those who did make it to Canadian shores often faced racism in extreme forms such as the head tax for Chinese immigrants, or the gnawing bigotry and discrimination faced by the Irish, by Italians and by the DPs of Eastern Europe after the Second World War to name a few. Yet despite the Canadian ambivalence to immigrants and refugees, they kept coming and we keptand keepaccepting them. By 2006, one in five Canadians was born somewhere else.

About a quarter of a million newcomers came to Canada in 2008 alone. Among them were eleven students who had been isolated without freedoms in remote camps in the poorest region of Kenya, refugees living in one of the worst protracted situations in the world. Their adjustment to life here may seem like an extreme example of the disorientation all newcomers experience, but it is a chapter in that important Canadian story.

I first was drawn into the lives of the students of the Dadaab refugee camps in February 2007, when I met two remarkable young Somalis who had spent most of their lives in the Kenyan camps after fleeing civil war in their country of birth. I was in Dadaab as a producer for CBC Television, working on short pieces about the fresh wave of arrivals in the camps fleeing a new round of violence in Somalia. While I was in the camps, I started working on a documentary that would follow two students who were preparing to come to Canada months later. I met Nabiho Farah Abdi and Ibrahim Aden Mohamed in the main CARE compound for aid workers who provide services to the three surrounding camps. Nabiho and Ibrahim had come for a lesson on how to write essays for Canadian university courses. After the class they both spoke excitedly about having been selected for scholarships to Canadian universities. Nabiho said she wanted to become a universal person and to see what the real world was like. Ibrahim described Canada as the country of his dreams. The two were full of gratitude for the opportunity theyd been given. Although they knew little about Canada, they believed it was a country of tolerance. As the day drew near for their departure, their excitement became muted, tinged with anxiety and a growing realization that they were leaving everything theyd ever known behind. In Nairobi, before her departure, Nabiho told a CBC crew that she was happy, but in another part not happy. Its so painful to leave your mother, your sisters and brothers. Ibrahim described his feeling as a mixture of happiness and worry.

Six months after I met them in Dadaab, I arranged for CBC crews to follow Nabiho and Ibrahim during their first days in Canada for The National documentary The Lucky Ones, which focused on the initial shock of displacement. When Nabiho arrived at the airport in Regina, she tried to go around the camera to hug me. I was the only face she knew in a strange new world. She cried as she waited for her luggage, thinking of the mother who had raised ten children alone in a refugee camp and encouraged them all to learn about the world beyond the camp, encouraged them to studya mother who was now so far away. On her first morning in Canada she called home telling her mother she wanted to go back. After three days of realizing shed gained new freedoms but had lost everything familiar, she said her chances of adapting were fiftyfifty. I bowed out of her life then, only occasionally checking in on her adjustment.

![Goodwin - Fatal colours : the battle of Towton, 1461 ; [Englands most brutal battle]](/uploads/posts/book/98484/thumbs/goodwin-fatal-colours-the-battle-of-towton.jpg)