The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Ahmed (Gab) husband of Isha, born around 1970 and came to Dadaab following the death of their livestock during the drought of 2011.

Apshira wife of Tawane, also his cousin, born in Kenya in 1985 and came to Dadaab voluntarily to live with Tawane in 2003.

Billai wife of Nisho, born in 1995 in southern Somalia, came to Dadaab with her family fleeing the famine in 2011.

Christine daughter of Muna and Monday, born in Dadaab in 2011.

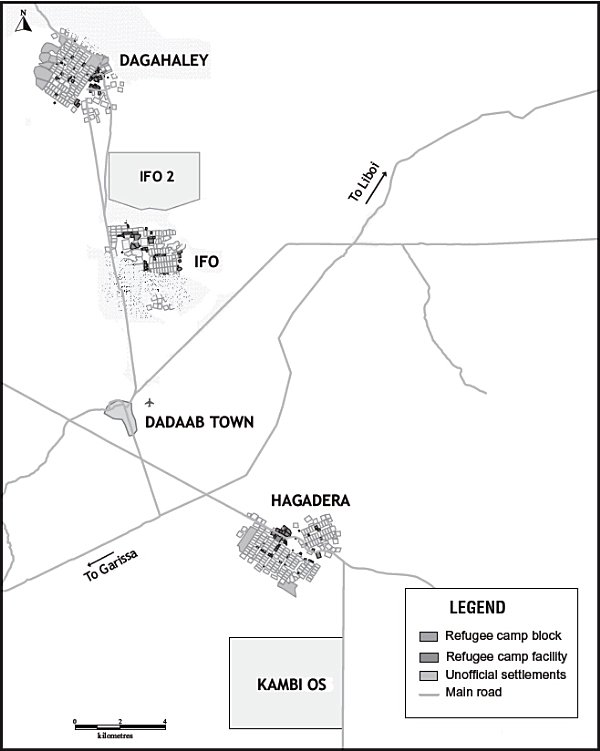

Fish friend of Tawane and sports chairman in Hagadera camp, born near Kismayo in 1984 and came to Dadaab with his mother fleeing the civil war in 1992.

Guled husband of Maryam, born in Mogadishu in 1993, came to Dadaab fleeing al-Shabaab in 2010

Idris father of Tawane, born around 1950, came to Dadaab after losing two sons in the civil war in 1991.

Isha wife of Ahmed (Gab), born in Somalia around 1970, came to Dadaab with her five children escaping the famine of 2011.

Kheyro a student in the camp and later a teacher, came to the camp aged two, with her mother, Rukia, fleeing civil war in 1992.

Mahat casual labourer in the market and friend of Nisho, lost his father in the war and came to Dadaab with his mother in 2008, aged eight or nine.

Maryam wife of Guled, born in 1992, she followed him from Mogadishu to Dadaab in 2011.

Monday husband of Muna and former Lost Boy, born in Abyei, Sudan in 1981, arrived in Dadaab via several refugee camps in Ethiopia and Kenya in 2004.

Muna wife of Monday, born in Somalia in 1990, came to Dadaab aged six months with her parents in 1991 after most of her extended family were killed.

Nisho porter in Ifo market and husband of Billai, born en route to Dadaab in 1991 as his parents were fleeing the civil war in Baidoa, central Somalia.

Professor Indha Dae (White Eyes) born blind but later recovered his sight, a trader and then journalist, came to Dadaab aged four or five with his grandmother, fleeing the fighting in 1991.

Tawane husband of Apshira, businessman and youth leader, came to Dadaab aged seven with his family in 1991 after his brothers were killed in the civil war.

The White House, Washington DC, 31 October 2014

The members of the National Security Council were arranged around a grey table in a grey room without windows. On the walls, photographs depicted a sporty-looking President Obama on a recent trip to Wales for a NATO summit. The officials attending from the Africa desk were a middle-aged white man leaning back slightly in his chair; a younger one in a tight new suit who hunched forward and stared at a notepad; a short blonde woman who sat perfectly still throughout the whole meeting with her hands in her lap so that her impassive face appeared to float above the surface of the table; and the chief, a well-dressed woman in tweed skirt and matching tan shoes, expensive, who smiled and nodded and said little, just like the rest of them.

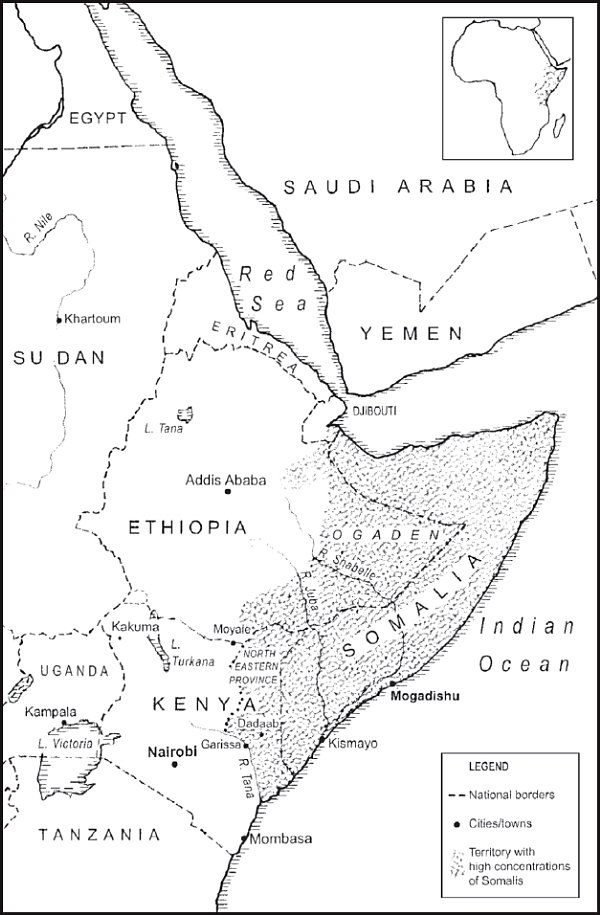

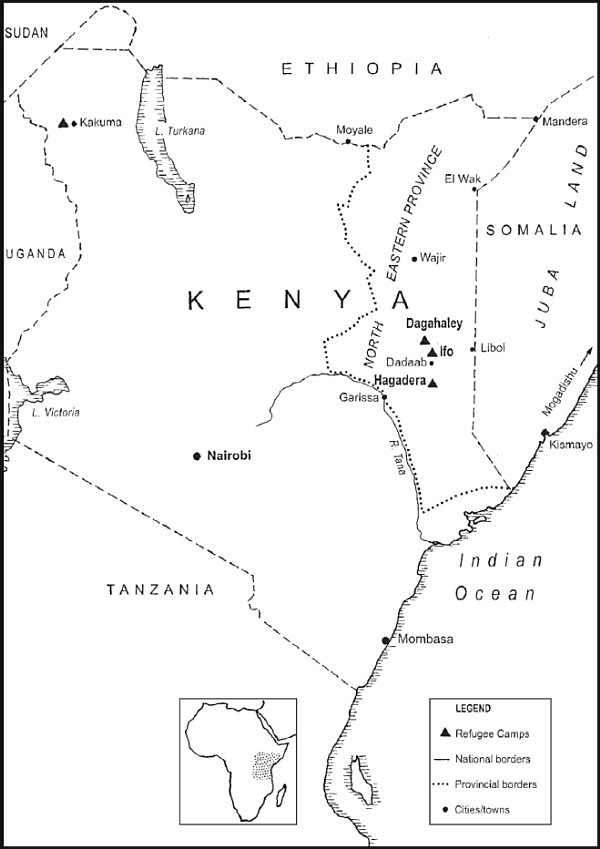

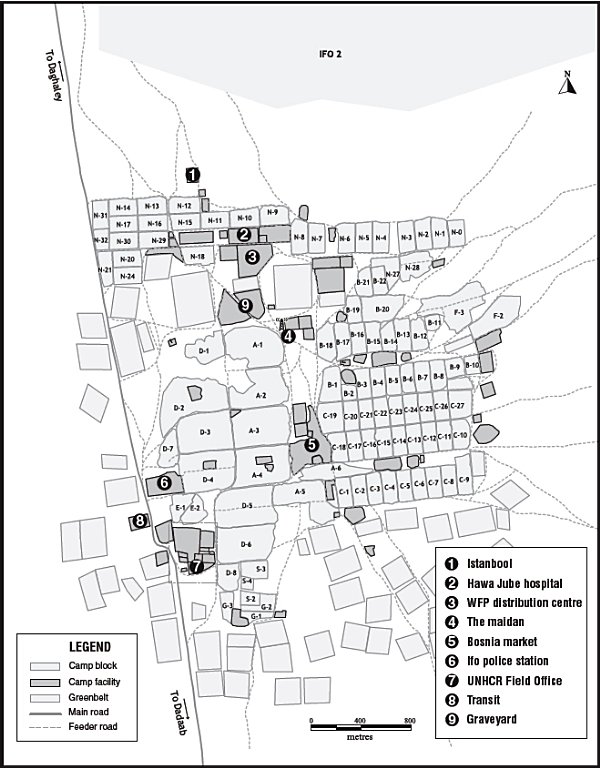

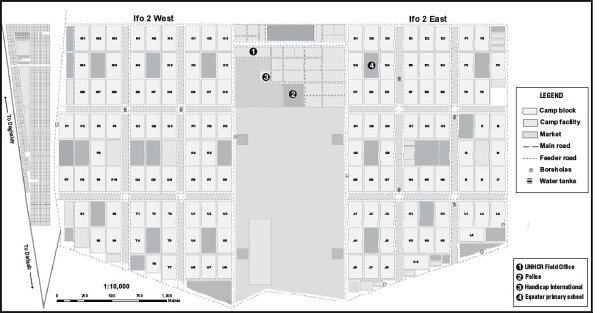

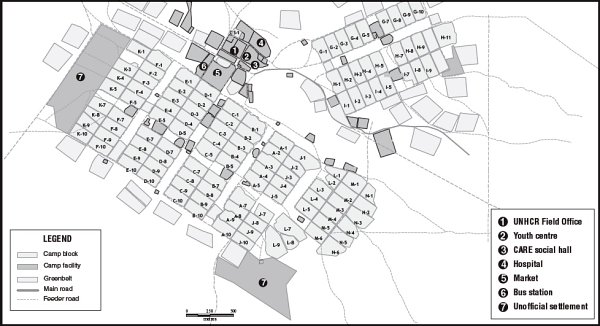

I was there to brief the NSC about Dadaab, a refugee camp located in northern Kenya close to the border with Somalia. Since 2008, when al-Shabaab, an al-Qaida-linked militant group, assumed control of most of Somalia, the Horn of Africa has been at the fulcrum of what policymakers like to call the arc of instability that reaches across Africa from Mali in the west, to Boko Haram in Nigeria, through Chad, Darfur, Sudan, southern Ethiopia, Somalia and on to Yemen, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan and Afghanistan in the east. Extremism in Africa has been rising up international agendas as terrorist attacks have mushroomed. Twelve months earlier, al-Shabaab had attacked Westgate shopping mall in the Kenyan capital Nairobi. And six months after our meeting, al-Shabaab would hit the headlines again with the slaughter of 148 students at Garissa University College in the north of the country. After both attacks, the Kenyan government claimed the gunmen came from Dadaab and vowed to close the refugee camp, branding it a nursery for terrorists. In essence, the NSC wanted to know, was this my experience? The US is the main funder of the camp.

I had spent the previous three years researching the lives of the inhabitants of the camp and five years before that reporting on human rights there. How to describe to people who have never visited, the many faces of that city? The term refugee camp is misleading. Dadaab was established in 1992 to hold 90,000 refugees fleeing Somalias civil war. At the beginning of 2016 it is twenty-five years old and nearly half a million strong, an urban area the size of New Orleans, Bristol or Zurich unmarked on any official map. I tried to explain to the NSC officials my own wonder at this teeming ramshackle metropolis with cinemas, football leagues, hotels and hospitals, and to emphasize that, contrary to what they might expect, a large portion of the refugees are extremely pro-American. I said that the Kenyan security forces, underwritten by US and British money, weapons and training, were going about things in the wrong way: rounding up refugees, raping and extorting them, encouraging them to return to war-racked Somalia. But I sensed that the officials were not really listening. I was asking them to undo a lifetime of stereotyping and to ignore everything that they were hearing in their briefings and in the media.

My friends, the refugees in the camp, had been so excited to hear that I was going to the White House! Here I was, at the pinnacle of the US policy-making machine, poised to exercise my influence, yet floundering. Raised on the meagre rations of the United Nations for their whole lives, schooled by NGOs and submitted to workshops on democracy, gender mainstreaming and campaigns against female genital mutilation, the refugees suffered from benign illusions about the largesse of the international community. They were forbidden from leaving and not allowed to work, but they believed that if only people came to know about their plight, then the world would be moved to help, to bring to an end the protracted situation that has seen them confined to camps for generations, their children and then grandchildren born in the open prison in the desert. But the officials in the grey room saw the world from only one angle.