A Oneworld Book

First published by Oneworld Publications 2012

Copyright Ben Rawlence 2012

The moral right of Ben Rawlence to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-85168-927-9

Ebook ISBN 978-1-78074-095-9

Typeset by Cenveo Publisher Services

Cover design by Dan Mogford

The illustration credits on pp. 2912 constitute an extension of this copyright page

Map and ornament artwork copyright Bill Sanderson 2012

Oneworld Publications

185 Banbury Road Oxford, OX2 7AR, England

Stay up to date with the latest books, special offers, and exclusive content from Oneworld with our monthly newsletter

Sign up on our website

www.oneworld-publications.com

Still there are too many people in Europe who only know how Africans are dying, not how they live.

H ENNING M ANKELL

Prologue

IN MANONO, THE RADIO sits on a small four-legged wooden stool in the mud, its aerial bent in several places, the battery door held together with tape. Arranged in a rough circle around it are about twenty men and several women, sitting on benches, chairs and upturned crates; a few are leaning against the pine trees that rustle quietly in the night breeze. They are priests, nuns, teachers, a waitress. Some hold their chins in their hands, others pull on cigarettes, and every now and then an exclamation goes up in reaction to the news. The radio speaks of war in the north, of politics in Kinshasa and of more war in Iraq. An orange moon lies sullen in the treetops that frame the compound where we sit, but I am the only one admiring it.

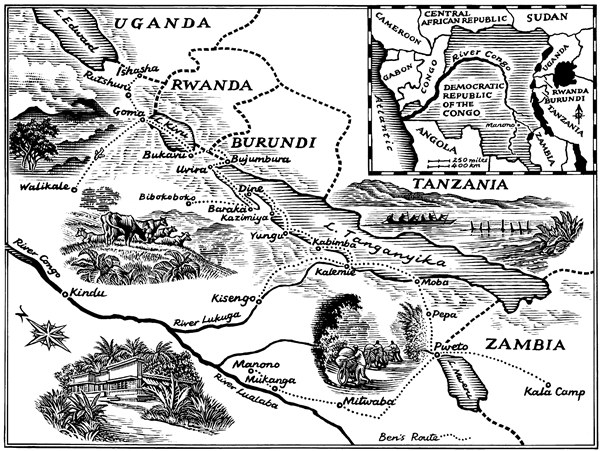

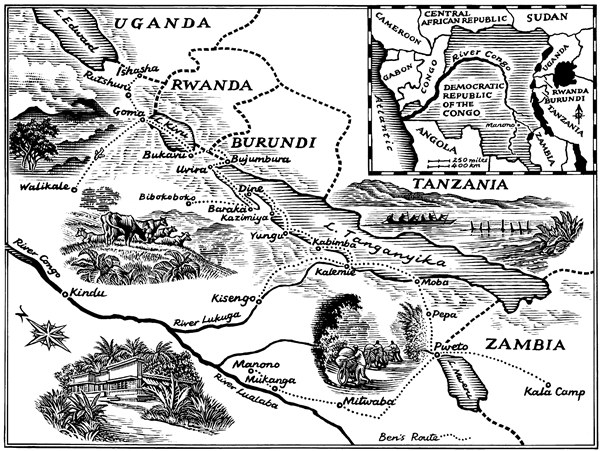

Manono lies deep in the forest on the upper reaches of the Congo River in the east of the country, four days ride on a motorbike from the shores of Lake Tanganyika. The main road linking it to the other towns of the east has been destroyed; goods arrive by barge or on the occasional humanitarian organisation plane that, when the weather allows, lands on the old airstrip. The people listening to the radio know what is happening in Baghdad but have little idea about the news from the town of Kongolo, several days journey up the river, or Mitwaba, five days walk to the south. Like thousands of other towns emerging from Congos recent wars, Manono is an island in a sea of forest. News reaches Manono but news of Manono rarely reaches anywhere.

The lost city

Manono, 1966

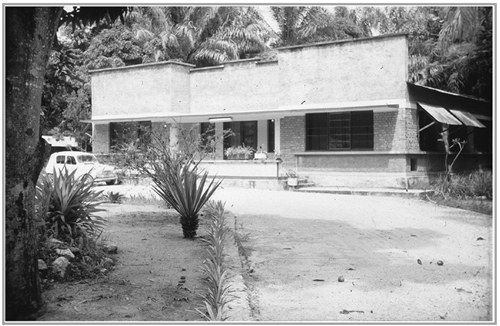

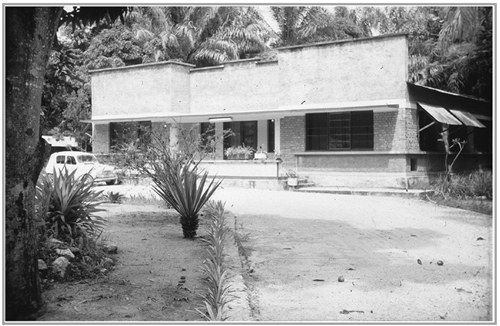

A WIDE GRAVEL DRIVE leads up to a house. A car stands in front. The house is rectangular and so is the covered veranda that looks out over a lush tropical garden. The shadows of tall trees creep across the drive and obscure half of the house. The visible half is a fiesta of right angles: a jutting roof above the porch, square windows and sharp flat slabs that cap a wide ridge of concrete on the upper floor. From the way the light bounces off the shiny surface of the car, it seems to be the middle of a hot afternoon. Perhaps the master and mistress are having a siesta and barefoot, uniformed servants are sweeping the floors. Is there a figure in the doorway; is that a slight lightening of the shadow, a white face peeking out at the jungle?

Opposite the house in the old photograph, beyond its frame, are other villas of modern design. One is smaller, with a stepped roof in imitation of a medieval castle, and geometric patterns scored in the concrete walls. A veranda slices the house in two, like a knife through fruit. The windows of the one next door are round portholes, painted blue, two on the front and one on the side, giving the house the look of a ship beached among the palms. Beyond is another fanciful villa, with a long curving faade, next to that another, then another, the houses dotted through a forest that has been fenced and thinned into garden but which nevertheless threatens to swallow, at a moments notice, this beautiful art deco suburb.

The street is made of marram; crushed and pressed gravel. It bears the fresh tyre marks of elegant automobiles: Citroens, Renaults, and Peugeots, with long running boards, rounded bonnets and polished hubcaps. At the end of the street is a pair of huge mango trees, which shade one end of a swimming pool that otherwise shimmers in the heat. Black and white children splash, or hurl themselves off the high board under the careful gaze of lifeguards. From his little wooden hut, the attendant comes out to sweep the paving stones and collect any mangoes that fall into the pool during the season.

Bordering the pool is the school; its oblong walls cut with tall metal windows arranged in neat symmetrical lines. Beyond, tennis courts lie hot and red, their brushed clay smooth and calm against the unruly thatch of the elephant grass. Behind the courts lies the golf course; rich, green, billiard-table baize, pocked with sand, where men in white circle, halt, swing and pirouette like dancers in a strange, slow-motion ballet.

The road curves past the golf course and the tennis courts in a wide arc strung with electricity pylons, until it reaches a small roadblock. There, policemen salute and raise the barrier for the cars of those who live in the wealthy quarter so they may drive down the long, broad avenue towards the cathedral, with black tiles and a gabled roof; a Flemish refugee adrift in the African bush.

The streets of the town are lined with little box hedges that squat beneath telegraph poles. In the centre is a huge four-storey brewery that makes beer for export across the region. At the end of another wide boulevard, fringed with mango trees, looms the mine works: the source of the towns prosperity and the regions wealth. It is a massive operation, employing thirty thousand people and state-of-the-art technology: Africas only tin works, smelting its own ores and exporting pure metal. The tailings form a great towering white mountain that matches in its tidy geometry the modernist cubes of the villas in the town below.

This is the town of Manono in the newly independent, former Belgian colony of Congo. The airport terminal has an arched doorway, and a rectangular tower that looks as if it were made of Lego. Here, other Belgian, French, British, German, Greek, Portuguese, South African and Lebanese colonists from across central Africa touch down for a holiday, a tantalizing taste of modern civilisation away from their jobs but closer to home than Europe, weeks away by boat. New planes are beginning to hop across the continents but they still take a while.

The Belgian mining company Gomines has made Manono into a model modern town. Wealthy visitors stroll down the boulevards, lamp-lit courtesy of the hydroelectric power station. The supermarch, in its sleek whitewashed skin, over three storeys high, is stocked with all the latest European products, as well as beer, meat and dairy goods from Katangas modern farms and factories. Well-dressed white teenagers in the cafs near the petrol station perch on red leather, listen to rock-and-roll, and eat ice creams, just like their peers in the USA.

Next page