Copyright 2015 by Lisa J. Shannon

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs, a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the US by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Book Design by Pauline Brown

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

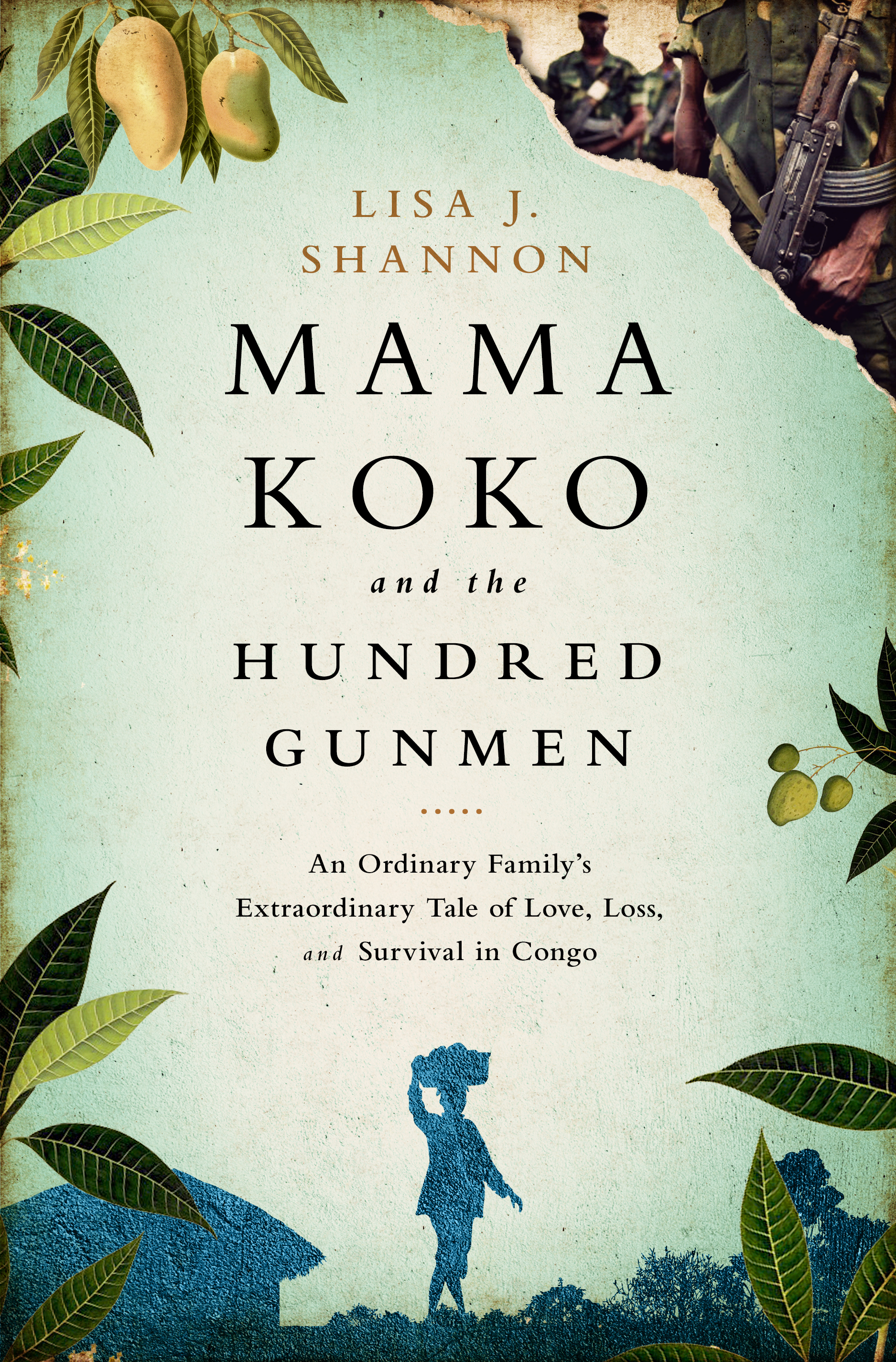

Shannon, Lisa, 1975 author. Mama Koko and the hundred gunmen : one ordinary familys extraordinary tale of love, loss, and survival in Congo / Lisa J. Shannon.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

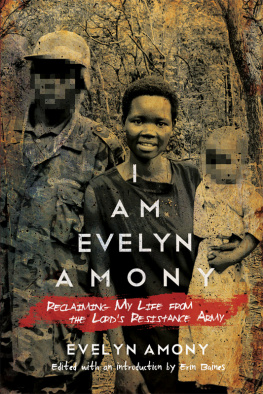

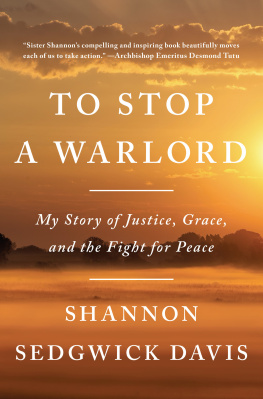

ISBN 978-1-61039-445-1 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-61039-446-8 (e-book) 1. Women and warCongo (Democratic Republic) 2. War victimsCongo (Democratic Republic) 3. AtrocitiesCongo (Democratic Republic) 4. Congo (Democratic Republic)Social conditions21st century. 5. Thelin, Francisca. 6. Thelin, FranciscaFamily. 7. Congolese (Democratic Republic)Biography. 8. CongoleseUnited StatesBiography. 9. Shannon, Lisa, 1975 TravelCongo (Democratic Republic) 10. Lords Resistance Army. 11. Kony, Joseph. I. Title.

HQ1805.5.S525 2014

305.9'0695096751dc23

2014035568

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Heritier

Contents

I Imagine

Sometimes I imagine standing in the corner of the family coffee plantation, maybe in a nearby field, watching the family hover around Rogers body. The day the attacks started, they found him off the road by the river, in the bushes under a shroud of palm leaves, hacked, his mouth and wounds boiling with a greedy riot of insects.

Roger was the first to die. When the family found his body, neighbors were already rushing to gather their bare essentials, slipping away on the footpaths and back routes, as inconspicuous and silent as a mass exodus can be. Yet Rogers family carried his body back to the coffee plantation for burial.

I picture the family as they linger: mulling around, digging the grave, dressing him for hasty burial. Mama Cecelia kneeling over him, washing away the blood, her calloused fingers sweeping clean every crevasse and axe wound bourgeoning with insects.

Rogers pre-teen sons sulk in the corner, the spark in their eyes draining fast. His church-going wife Marie, tall and full of grace, presses her fingers into a rosary, leaning on Jesus to get her through each imposing minute. Rogers younger brother and another of his sons, each on the verge of manhood, dig the grave. His father Papa Alexanders eyes track the bloodthirsty crawlers shaken free by Mama Cecelia as they make their rapid retreat into dusty fields or dark hiding places, like the neighbors now on their way to Sudan. Maybe he surveys the scene, scanning his coffee kingdom, watching the brush for movement, for clues that scream Times up.

A fatal mistake hangs in the air, between their sighs. The weight of it settles around them, like their hands on each others shoulders. They do not know that the shreds of human dignity exercised with rituals like washing a beloveds dead body have retreated with the termites into the fields. There would still be time, if the family only knew how to hear Rogers wounds whisper their warning: You are no longer human. Run.

Yet they stay, washing their beloved Roger and preparing him for the cold earth. With each swig of tea, each soothing stroke of wet cloth pressing closed Rogers gaping skin, muffling his axe wounds siren screams, the family exchanges what they do not know will be their final glances between one another.

A Day Like Any Other

The same day they buried Roger, on the other side of the world, Rogers cousin Francisca was up at five in the morning, as she was most weekdays, to put on the pants as they would have said back home in Congo. It meant the man goes to work. Francisca bypassed her stacks of African-print dresses and instead zipped up her slacks right alongside her American husband Kevin, a Peace Corps volunteer turned buttoned-down engineer.

On the way out the door, Francisca caught a glimpse of herself in the mirror: fresh braids bound tight to her head in ornate patterns, shiny dark skin plump with lotion, a dash of ChapStick on her lips, the sum of her makeup routine. Clean and simple, like her mother Mama Koko taught her. Why cover up all that beautiful? Francisca greeted herself in the mirror, her coffee-colored eyes rimmed with blue beaming back. As always, she said out loud, Good morning, lovely!

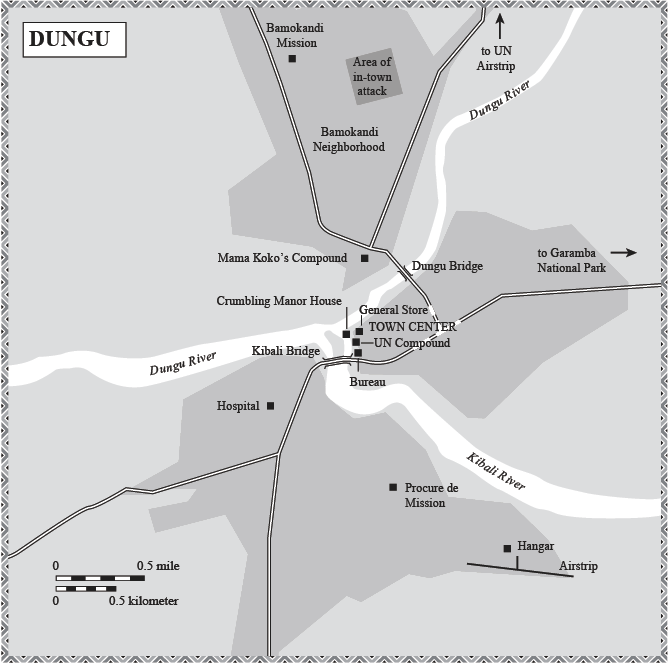

Craftsman bungalows pulsed past in the early morning light as Francisca drove to work. She pulled into a mammoth one-stop shopping center, inconceivable back home, compared to her towns one-room general store. Inside cavernous Fred Meyers, the ambient hum of the ventilation absorbed voices, rattling carts, announcements of spills in aisle nine. Fluorescents washed out the faces of shoppers roaming the windowless open space, packed twelve shelves high with everything from rib-eye steak and bananas on special to cement faeries for the garden, day-to-evening wear, fashion socks, hand blenders, assorted wrenches and paints, fishing gear, and diamond pendants promising to delight and last a lifetime. Everything you need, all in one stop: Youll Find It at Fred Meyers.

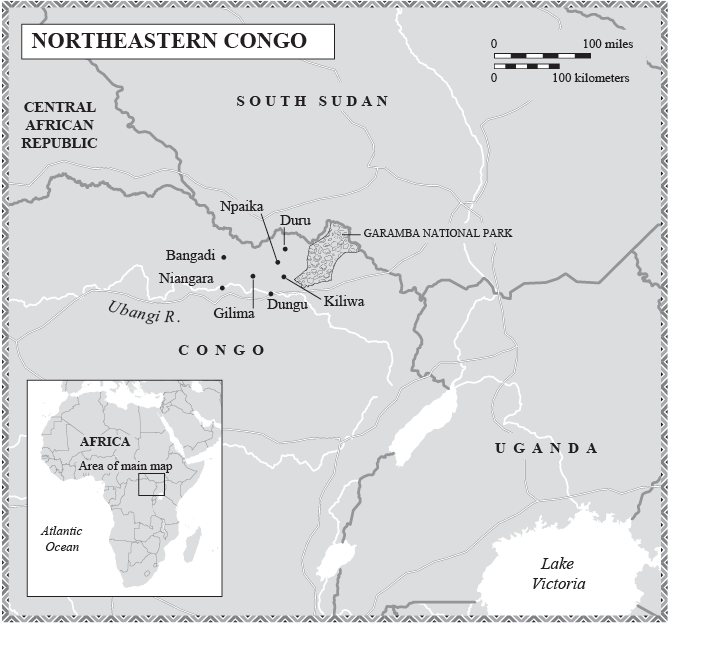

Francisca slipped on her chefs coat and pinned on her nametag: Francisca, Cheese Steward since 1996. Francisca had no background in cheese. There were no sample trays of brie and gruyere, no sharp cheddar finger sandwiches served with iced tea on the old wooden porch of her childhood castle, as the family called it, overlooking their coffee plantation in that far- northeastern pocket of Congo. Francisca spent her childhood summers roaming in the cotton fields, wading through the cassava leaves, gorging on mangoes and termite-oil delicacies, not cheese.

Francisca didnt even like cheese, though her customers would never know it. She thought of it as white peoples food. She got the job as cheese steward because she spoke French; French is useful when it comes to cheeses.

That morning, it was out to the floor to organize the olive bar, crowned with gourmet salts from faraway places like the Black Sea and the Himalayas. Anyone browsing the cheese display who listened in would have heard Francisca singing hymns to no one in particular. By the time Francisca finished arranging the display of packaged cuts of cheese in take-home wedges, Roger was already buried on her familys coffee plantation. By then, the family members had split up, and more of them had been murdered by axe.

Francisca was home by noon. She shed her work pants, which reeked of cheese and olive juice, and slipped on one of her African-print skirts. In her living room, surrounded by remnants of home, many-hued dark wood trim blending with ubiquitous African figurines and safari-themed wallpaper, Francisca turned on African music, nice and loud, and danced Congolese style, heavy on the hip thrusts and booty wagging.