ARMY OF GOD

Joseph Konys War in Central Africa

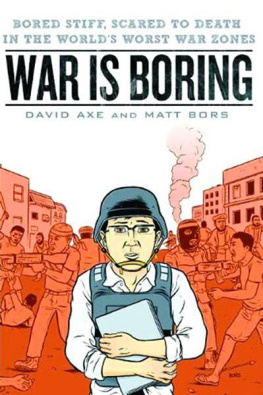

DAVID AXEandTIM HAMILTON

PUBLICAFFAIRS

New York

Copyright 2013 by David Axe and Tim Hamilton.

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs, a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Book Design by David Axe and Tim Hamilton

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012955375

ISBN 978-1-61039-300-3 (EB)

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I WAS NO STRANGER to war. But to me this war was, well, strange.

The fighting in the Democratic Republic of Congo was like nothing Id experienced in my then five years as a war correspondent for Wired, Voice of America, and other media outlets. Id covered conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, Lebanon, East Timor, Somalia, Chad, and other countries. Id witnessed gunfights, bombings, suicide attacks, artillery duels, airstrikes, and mob violence. Id been shot at, blown up, arrested, and kidnapped twice.

But Id never before seen the kind of cruelty thats routine in Congos overlapping rebellions, terror campaigns, and abusive internal security deployments. Bullets are expensive; machetes are a favored weapon. But even machetes are expensive compared to one implement thats totally free: the human body. In a world where rape as a weapon of war is increasingly rare, in Congo sexual violence is still a preferred tactic. Its with good reason that one U.N. official dubbed the DRC the rape capital of the world.

There is no single war in Congo, there are several. As I write these words the DRC is a battleground for a rebellion of former army soldiers calling themselves the March 23 (M23) movementand for the remnants of the Rwandan Hutu Power group, known by its French acronym, FDLR. The country has become a theater for tense, and sometimes deadly, face-offs between Congolese government troops and those of neighboring Rwanda, an historic foe of the DRC.

But most prominently to the outside world, Congo is the base of the Lords Resistance Army, a once-Ugandan rebel group that fled its homeland and, loosed from its original political aims, now fights to survive. Dominated by its mysterious, volatile founder Joseph Kony and governed by a complex body of rules, customs, and superstitions, the LRA is ostensibly a fundamentalist Christian religious movement, an army of God. In reality it bears no resemblance to Christian institutions elsewhere. Its methods are rape and pillage. Its major aim is to sustain itself.

It is neither the first nor the most destructive armed group to ever occupy the DRC; it wont be the last group to terrorize the Congolese forest. But the LRA is unique for its odd, even terrifying, cultureand for its tenacity. Constantly on the move and periodically refreshed with the enslaved and gradually brainwashed young men and women it captures on the march, the LRA has survived in Congo for nearly a decade despite the efforts of several governments and world bodies to destroy it. Kony s fighterswho currently number between 100 and 600, according to the most reliable sourceshave killed thousands, abducted tens of thousands, and displaced hundreds of thousands.

It was 2010 when I decided to go to Congo. My reasons were deeply personal: By then I had reported from all the worst places I could think of except Congo. Like Iraq, Afghanistan, and Somalia, it was on a secret list inscribed on my heart in black ink. I went because I could no longer make excuses to myself for not going. I went seeking answers:

Where had the LRA come from? Id researched the formal answer: it came from northern Uganda during a time of civil unrest. But my research didnt answer the more fundamental question. What ambitions, convictions, fears, and impulses motivated Kony and his followers? I wanted to map the emotional and spiritual landscape of the group.

Likewise, what was it like living under the shadow of the LRA? Was it hard to survive in the remotest part of a remote country where the government is often as frightening as the rebels, terrorists, and criminals? What did it feel like knowing the killers could strike at any timeand that likely no one would come to your aid when they did? What about the children whove never known a world without the LRA? Kids are adaptable, but what did it mean to adapt to a world of rape and bloodshed?

I also wanted to gauge the rest of the worlds responsibility. What, if anything, could and should the world do about the LRA? Without a doubt, Congos long history as the subject of uncaring colonial powers had contributed to its present lawlessness. Already the DRC was the subject of one of the largest U.N. peacekeeping operations ever. Was more foreign intervention the solution or the problem? As a member of the Western media, was there anything I could do to help?

My timing was fortuitous. In late 2010, Congo was at a crossroads, years of Chinese investment had transformed the infrastructure of the capital, Kinshasa. Growingties with the outside world meant more trade, incrementally better governance, and greater demand among everyday people for goods, services, rights, and real democracy. After several botched military operations against the LRA, the U.N. was rethinking its approach to peacekeeping.

And the U.S. government, all but absent from the DRC for many years, was getting more involved. American aid workers and advocates were on the ground. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited Congo in late 2009. In May 2010, President Barack Obama signed a law requiring his administration to formulate an official strategy for defeating the LRA. Initial contingents of American troops were arriving to hand out medicine and help train the Forces Armees de la Republique Democratique du Congo (FARDC), the Congolese army. In a very real way my own presence represented another small facet of the increasing U.S. involvement in the DRC.

I flew into Kinshasa in September 2010. In that teeming city of eight million in the DRCs more-developed west, I met up with members of the North Dakota Army National Guard, deployed to Congo for a medical exercise with the FARDC. Their goal: to teach the Congolese army how to actually help their own people.

After the American soldiers departed, I shifted gears. I spoke to the U.S. embassy about efforts to reform the Congolese government. I interviewed the heads of aid groups struggling to shore up the collapse of eastern communities under siege by the LRA and other armed groups. I visited a home for former child soldiers who had been liberated from the groups enslaving them.

Then I flew east in a plane belonging to the U.N. World Food Program. I landed in Dungu, a small town deep in the heart of LRA country. The FARDC camped on the outskirts near two bases controlled by the U.N. peacekeeping force. Aid groups maintained offices in town. The Catholic Church, headed by native and white priests, served as the glue that held all the disparate efforts together. I attended a church service one morning to see for myself the depth and power of Congolese faith.

I visited the troops and the humanitarians. I accompanied military patrols escorting food aid to nearby settlements. I observed the heartbreaking daily rounds of a young priest who served as a sort of walking hotline for myriad pleas by the sick, injured, and destitute. And I met the victimsmen, women, boys, and girls who had been assaulted, kidnapped, enslaved, raped, and mutilated by the LRA.

Next page

![Atkinson - An army at dawn: [the war in North Africa, 1942-1943]](/uploads/posts/book/178818/thumbs/atkinson-an-army-at-dawn-the-war-in-north.jpg)