Contents

Page-list

Guide

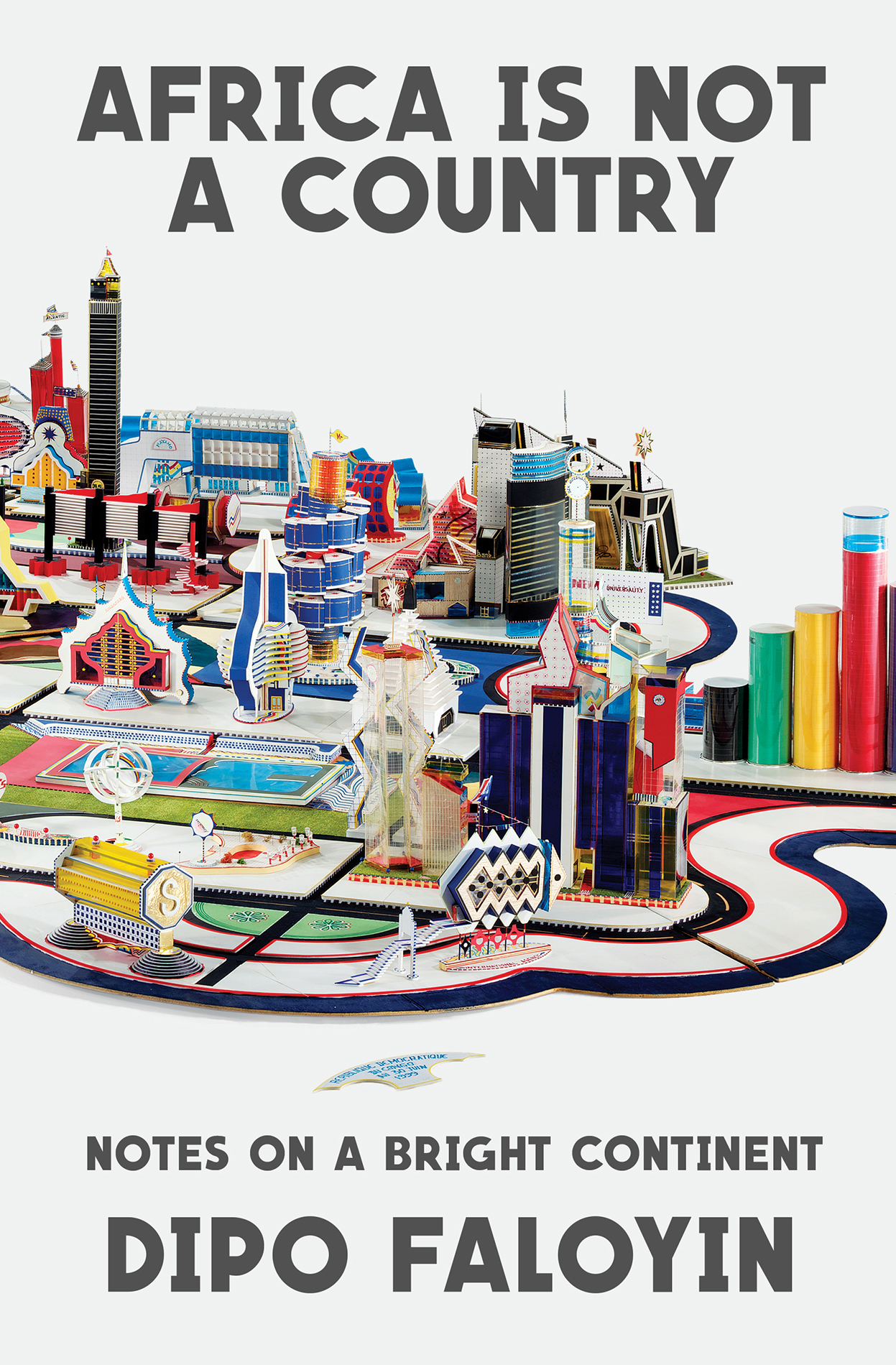

AFRICA

IS NOT A

COUNTRY

Notes on a

Bright Continent

Dipo Faloyin

Copyright 2022 by Dipo Faloyin

First American Edition 2022

First published in the United Kingdom by Harvill Secker, an imprint of Vintage, a part of Penguin Random House UK under the title Africa Is Not a Country: Breaking Stereotypes of Modern Africa

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, downloaded from avxhm.se, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

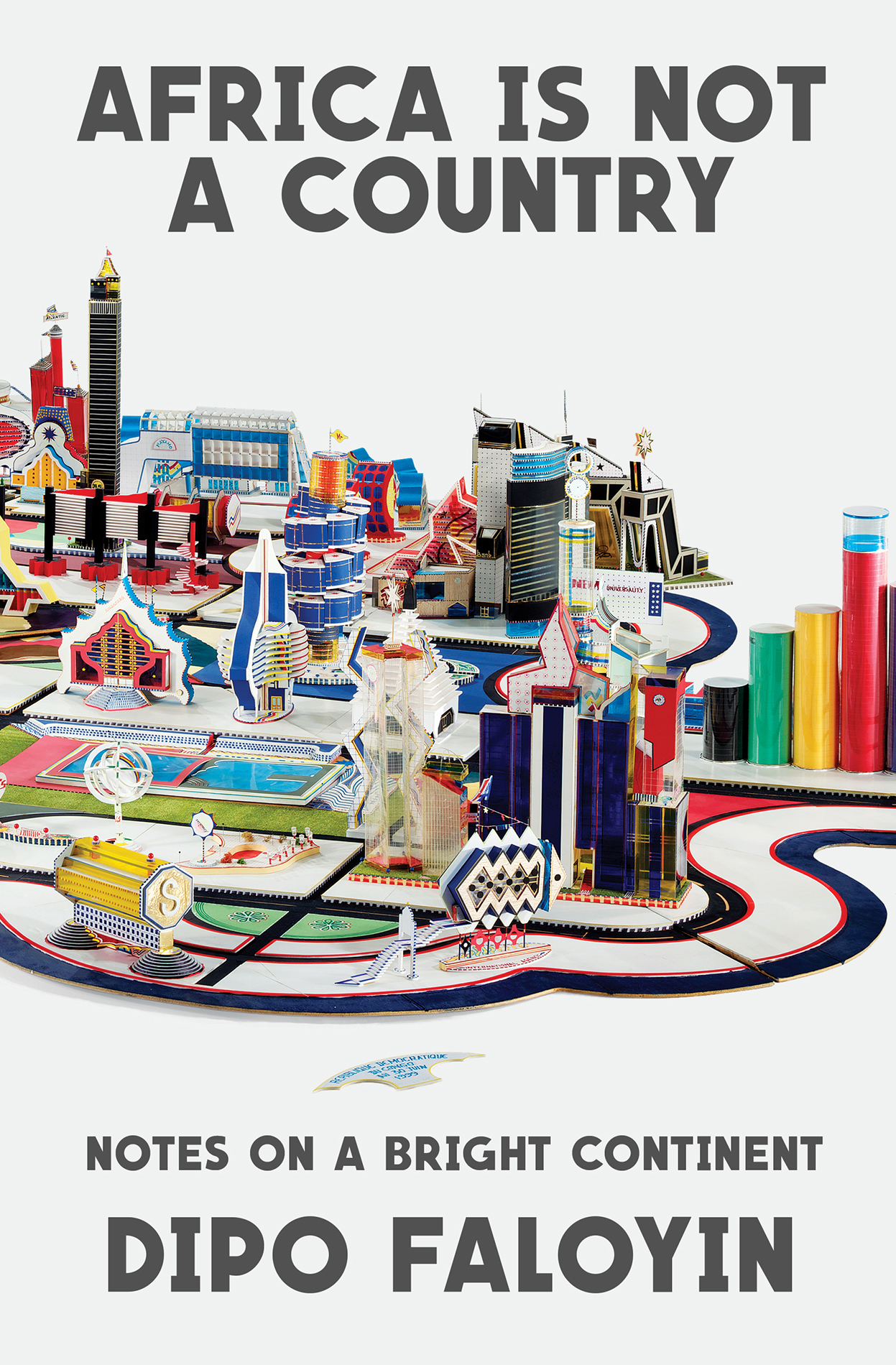

Jacket design: Jaya Miceli

Jacket artwork: Bodys Isek Kingelez, Courtesy of The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection

Production manager: Beth Steidle

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN 978-0-393-88153-0

ISBN 978-0-393-88154-7 (ebk.)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

Dedicated to the nations of my continent:

Olufemi, Olutosin; Vero, Temitope, Yewande; Feranmi, Sekemi, and Olivia.

Buku.

AFRICA IS NOT

A COUNTRY

Authors Note

I.

Assume any mention of the actions of an ethnic group refers to the leadership of that group at that time and does not reflect the majority beliefs of the entire community.

II.

Im not generically African. I am Nigerian. This book reflects my viewpoint as such.

[Insert generic African proverb here. Ideally an allegory about a wise monkey and his interaction with a tree, or the relationship between the donkey and the ant that surprisingly speaks to grand gestures of valour. Sign it off: Ancient African proverb]

If all I knew about Africa were from popular images, I too would think that Africa was a place of beautiful landscapes, beautiful animals and incomprehensible people, fighting senseless wars, dying of poverty and AIDS, unable to speak for themselves.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Contents

IDENTITIES form specifically.

I come from a place that exists somewhere between a pot of Jollof rice in the busiest kitchen in West Africa and a living room full of revolving main characters. I delight in discussion because I am forged from my familys most consistent ritual: gathering too many people in a confined space and arguing about nothing each person giving their opinion on each persons opinion. I was born to people with conflicting recollections of events where they were both present. I grew up surrounded by family forever complaining that someone else is not telling the story right, either in accuracy or with the requisite flair. In our home, history isnt written by the winner but by whoever speaks first.

My mother is a people person, a crowd-pleaser. She is never more comfortable than when she is uncomfortable, cocooned by unfolding events out of her control, where the solution is always a family meeting. From her I inherited my love for living in highly dense populations, ensconced in noise and all-round activity; a deep joy at being boxed in by a jukebox of experiences and an extensive bus network. My mother always stays for one more song. I always stay for one more song.

My father is an extrovert on his own terms, extremely at ease in his own skin, with an urgent need to just be. His current pace is a counterweight to motion. If he could design a perfect day, it would involve a morning nap. From him I take a tranquil disposition: things are probably never as bad or as good as they seem at first. At our fastest, we are slow walkers; at our slowest, as my sister once noted, we may as well be strolling backwards.

I am half Yoruba and half Igbo. They say Yorubas just want to have a good time and Igbos just want to have a good life, which means I am programmed, anytime anywhere, to never automatically turn down an invite without, at the very least, asking some follow-up questions. I have three older sisters, which means 23 per cent of my life has been spent mourning the points I wish I had brought up in a long-finished argument.

I come from a confusingly sublime matrix of who is actually a blood relative, and a deep appreciation of heat, both in taste and touch, and the healing powers of pepper soup. I was raised with a strong belief that it is an auntys duty to mind your business and that it is impossible to have too many cousins two concepts Im triggered to defend. I am from a home with an open-door policy. I am from a belief that to visit our home is to eat at our home, because food is the ultimate love language; food forgives sins and dispenses grace.

I was raised to get up early for church and stay up late for election nights. I am from a family that has never willingly gone on a beach holiday, and values intuition over organisation; a home where decisions are based on emotion rather than practicality. A strict childhood diet of arriving at events and airports too early has made me allergic to arriving at events and airports too early. Bedtimes were set, as was the understanding that children should be heard.

I am descended from a long line of bad poker faces, a clan genetically unable to hide the frustrations or joys etched in our hearts, however temporary. I am from silence being the ultimate punishment, and appreciating the eternal value of a dance floor bursting with people you love as the greatest man-made invention. I am from a philosophy that questions why you would ever order something new off a menu when you know exactly what you want; why order something new when you understand precisely who you are?

*

We are all the sum of a specific set of known knowns and more subtle influences that clash, combine and occasionally curdle. They are the intangibles that drive our most honest intentions and shape the essence of our personalities something that is often too intricate, too elastic and too personal to ever give full voice to accurately, however hard we try.

Instead, in all our interactions, we leave tiny breadcrumbs as clues to the inner sanctum of our complex identities. Its an unwitting, uneven collaboration between the big things: the genetics we inherit from our parents, and the life decisions we take after careful calculations; the subconscious things degrees of eye contact, automated anxieties; and the millions of things that thrive in the middle, whether its checking the weather before stepping outside, the perfect storage place for condiments, a commitment to coordinating socks.

Small patches of persona stitched together until they form someone real.

Not everyone is allowed a complex identity. Throughout history, individuals and entire communities have been systematically stripped of their personhood and idiosyncrasies, often to make them easier to demean, denigrate and subjugate and, in some cases, eradicate. Being able to define yourself openly and fully is a privilege; it is a grace many take for granted. The ability to walk into a meeting or an interview, or to interact with a police officer, and be given the respect and opportunity to present yourself without pre-judgement, can be life-defining, life-affirming and life-saving.

To strip an individual of that privilege is destructive enough. But when you apply this reductive treatment to an entire community, country or race, you create a poisonously false narrative that permeates for generations, until the fiction becomes fact, which in turn becomes an infected shared wisdom steadily passed down in schools, at family dinner tables, in words pressed into books, and in the images that populate our popular culture.