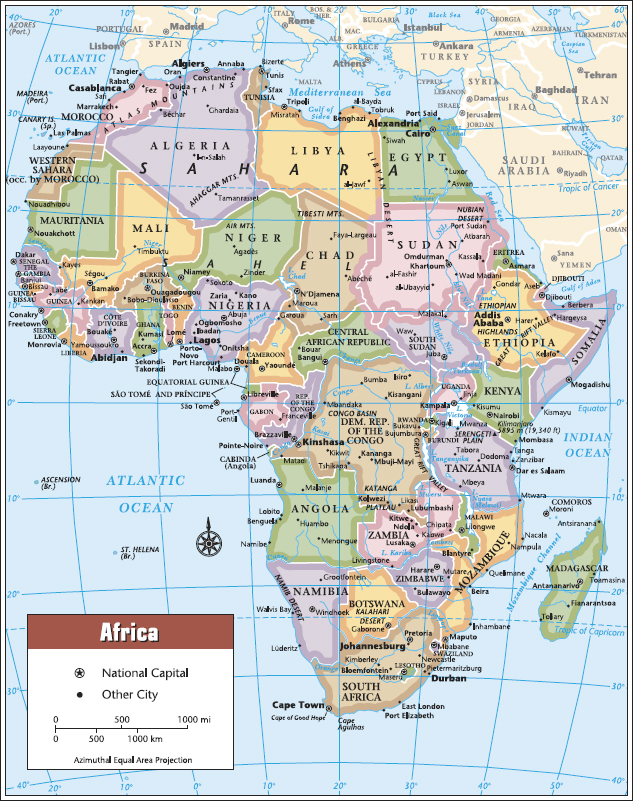

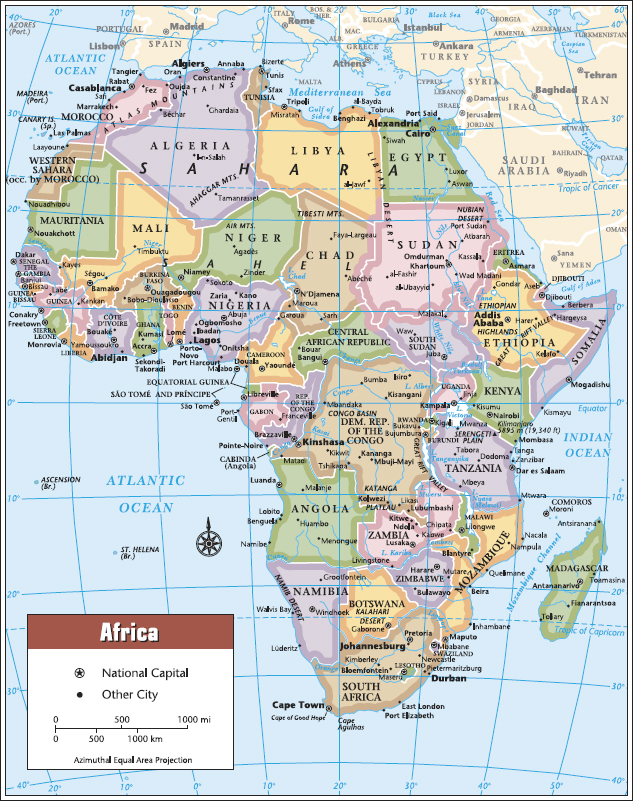

AFRICA: PROGRESS AND PROBLEMS

THE MAKING OF MODERN AFRICA

M ASON C REST P HILADELPHIA

M ASON C REST P HILADELPHIA

AFRICA: PROGRESS AND PROBLEMS

THE MAKING OF MODERN AFRICA

Tunde Obadina

M ASON C REST P HILADELPHIA

M ASON C REST P HILADELPHIA

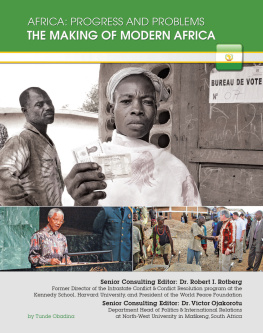

Frontispiece: A woman shows her voting card as she waits in line at a polling station in Grand Laho, Cte dIvoire, during legislative elections in February 2012. Some experts consider the increase in multiparty democratic elections and peaceful transitions of power in African nations as indicators of positive growth in the continent over the past decade.

| Mason Crest 450 Parkway Drive, Suite D Broomall, PA 19008 www.masoncrest.com |

2014 by Mason Crest, an imprint of National Highlights, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher.

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #APP2013. For further information, contact Mason Crest at 1-866-MCP-Book

First printing

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Obadina, Tunde.

The making of modern Africa / Tunde Obadina.

p. cm. (Africa: progress and problems)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4222-2944-6 (hc)

ISBN 978-1-4222-8889-4 (ebook)

1. AfricaHistoryJuvenile literature. 2. AfricaColonial influenceJuvenile literature. 3. AfricaSocial conditionsJuvenile literature. 4. AfricaEconomic conditionsJuvenile literature. I. Title. II. Series: Africa, progress & problems.

DT22.O23 2013

960dc23

2013013033

Africa: Progress and Problems series ISBN: 978-1-4222-2934-7

Table of Contents

AFRICA: PROGRESS AND PROBLEMS

A IDS AND H EALTH I SSUES

C IVIL W ARS IN A FRICA

E COLOGICAL I SSUES

E DUCATION IN A FRICA

E THNIC G ROUPS IN A FRICA

G OVERNANCE AND L EADERSHIP IN A FRICA

H ELPING A FRICA H ELP I TSELF : A G LOBAL E FFORT

H UMAN R IGHTS IN A FRICA

I SLAM IN A FRICA

T HE M AKING OF M ODERN A FRICA

P OPULATION AND O VERCROWDING

P OVERTY AND E CONOMIC I SSUES

R ELIGIONS OF A FRICA

by Robert I. Rotberg

Todays Africa is a mosaic of effective democracy and desperate despotism, immense wealth and abysmal poverty, conscious modernity and mired traditionalism, bitter conflict and vast arenas of peace, and enormous promise and abiding failure. Generalizations are more difficult to apply to Africa or Africans than elsewhere. The continent, especially the sub-Saharan two-thirds of its immense landmass, presents enormous physical, political, and human variety. From snow-capped peaks to intricate patches of remaining jungle, from desolate deserts to the greatest rivers, and from the highest coastal sand dunes anywhere to teeming urban conglomerations, Africa must be appreciated from myriad perspectives. Likewise, its peoples come in every shape and size, govern themselves in several complicated manners, worship a host of indigenous and imported gods, and speak thousands of original and five or six derivative common languages. To know Africa is to know nuance and complexity.

There are 54 nation-states that belong to the African Union, 49 of which are situated within the sub-Saharan mainland or on its offshore islands. No other continent has so many countries, political divisions, or members of the General Assembly of the United Nations. No other continent encompasses so many distinctively different peoples or spans such geographical disparity. On no other continent have so many innocent civilians lost their lives in intractable civil wars15 million since 1991 in such places as Algeria, Angola, the Congo, Cte dIvoire, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Sudan. No other continent has so many disparate natural resources (from cadmium, cobalt, and copper to petroleum and zinc) and so little to show for their frenzied exploitation. No other continent has proportionally so many people subsisting (or trying to) on less than $2 a day. But then no other continent has been so beset by HIV/AIDS (30 percent of all adults in southern Africa), by tuberculosis, by malaria (prevalent almost everywhere), and by less well-known scourges such as schistosomiasis (liver fluke), several kinds of filariasis, river blindness, trachoma, and trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness).

Africa is among the most Christian continents, but it also is home to more Muslims than the Middle East. Apostolic and Pentecostal churches are immensely powerful. So are Sufi brotherhoods. Yet traditional African religions are still influential. So is a belief in spirits and witches (even among Christians and Muslims), in faith healing and in alternative medicine. Polygamy remains popular. So does the practice of female circumcision and other long-standing cultural preferences. Africa cannot be well understood without appreciating how village life still permeates the great cities and how urban pursuits engulf villages. Africa can no longer be considered predominantly rural, agricultural, or wild; more than half of its peoples live in towns and cities.

Political leaders must cater to both worlds, old and new. They and their followers must join the globalized, Internet-penetrated world even as they remain rooted appropriately in past modes of behavior, obedient to dictates of family, lineage, tribe, and ethnicity. This duality often results in democracy or at least partially participatory democracy. Equally often it develops into autocracy. Botswana and Mauritius have enduring democratic governments. In Benin, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zambia fully democratic pursuits are relatively recent and not yet sustainably implanted. Algeria, Cameroon, Chad, the Central African Republic, Egypt, the Sudan, and Tunisia are authoritarian entities run by strongmen. Zimbabweans and Equatorial Guineans suffer from even more venal rule. Swazis and Moroccans are subject to the real whims of monarchs. Within even this vast sweep of political practice there are still more distinctions. The partial democracies represent a spectrum. So does the manner in which authority is wielded by kings, by generals, and by long-entrenched civilian autocrats.

The democratic countries are by and large better developed and more rapidly growing economically than those ruled by strongmen. In Africa there is an association between the pursuit of good governance and beneficial economic performance. Likewise, the natural resource wealth curse that has afflicted mineral-rich countries such as the Congo and Nigeria has had the opposite effect in well-governed places like Botswana. Nation-states open to global trade have done better than those with closed economies. So have those countries with prudent managements, sensible fiscal arrangements, and modest deficits. Overall, however, the bulk of African countries have suffered in terms of reduced economic growth from the sheer fact of being tropical, beset by disease in an enervating climate where there is an average of one trained physician to every 13,000 persons. Many lose growth prospects, too, because of the absence of navigable rivers, the paucity of ocean and river ports, barely maintained roads, and few and narrow railroads. Moreover, 15 of Africas countries are landlocked, without comfortable access to relatively inexpensive waterborne transport. Hence, imports and exports for much of Africa are more expensive than elsewhere as they move over formidable distances. Africa is the most underdeveloped continent because of geographical and health constraints that have not yet been overcome, because of ill-considered policies, because of the sheer number of separate nation-states (a colonial legacy), and because of poor governance.

Next page

M ASON C REST P HILADELPHIA

M ASON C REST P HILADELPHIA