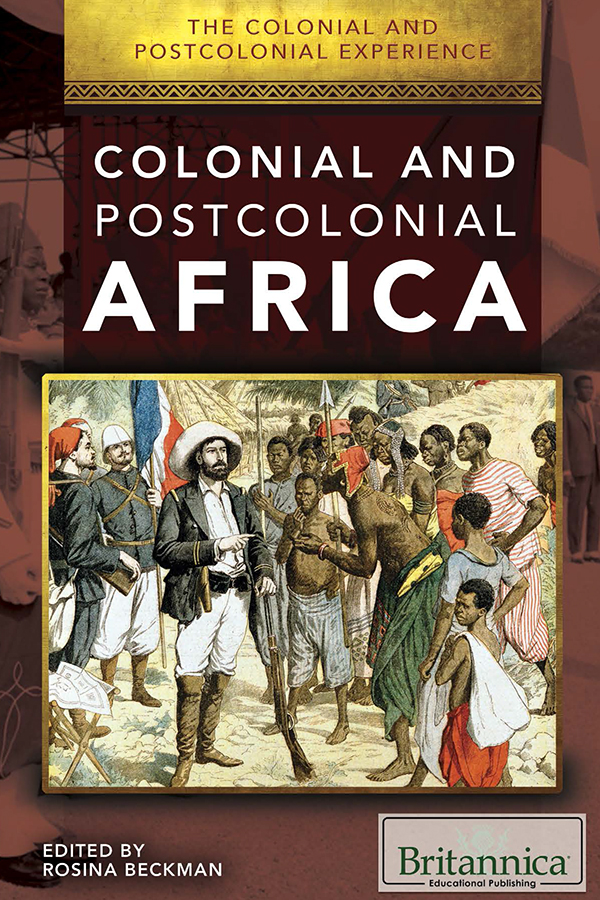

Published in 2017 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2017 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2017 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Executive Director, Core Editorial

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Amelie von Zumbusch: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Michael Moy: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Bruce Donnola: Photo Researcher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Beckman, Rosina, editor.

Title: Colonial and postcolonial Africa / edited by Rosina Beckman.

Description: First edition. | New York : Britannica Educational Publishing in Association with Rosen Educational Services, 2017. | Series: The colonial and postcolonial experience | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016022148 | ISBN 9781508102809 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: ColoniesAfricaHistory. | PostcolonialismAfrica. | AfricaHistory18841960. | AfricaHistory1960 | AfricaPolitics and government.

Classification: LCC DT29 .C572 2016 | DDC 960.3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016022148

Photo credits: AP Images; cover and interior pages patterned border element zizar/Shutterstock.com, background and border colors and textures Rawpixel.com/Shutterstock.com, Alted Studio/Shutterstock.com; back cover pattern pzAxe/Shutterstock.com.

CONTENTS

B etween November 15, 1884, and February 26, 1885, the major European nations held a conference in Berlin, Germany, at which they met to decide all questions connected with the Congo River basin in Central Africa. The general act of the Conference of Berlin declared the Congo River basin to be neutral, guaranteed freedom for trade and shipping for all states in the basin, forbade slave trading, and rejected Portugals claims to the Congo River estuary. Strange as it may seem that a meeting of Europeans in Germany would determine the power structure in Central Africa, the conference was the result of Western colonialismthe exploration, conquering, settlement, and exploitation of large areas of the world by the nations of Europe between the 16th and 20th centuries.

Africa has a long history of entanglement in Western colonialism. The age of modern colonialism began about 1500, following the European discovery of a sea route around Africas southern coast in 1488. The Europeans hoped that the new sea route would provide them direct access to valuable trade goods, such as silk and spices, from Asia. However, they quickly became interested in Africa as more than just a stop on the way to Asia. Gold came from Central Africa by Saharan caravan from Upper Volta (Burkina Faso) near the Niger, and interested persons in Portugal knew something of this. When Prince Henry the Navigator undertook sponsorship of Portuguese discovery voyages down the west coast of Africa, a principal motive was to find the mouth of a river to be ascended to these mines. The Portuguese thereby became the first colonial power in Africa, though theirs was less a territorial empire than a commercial operation based on possession of fortifications and posts strategically situated for trade. The Dutch, French, and British soon established outposts and forts in West Africa to compete with the Portuguese and eventually forced them out.

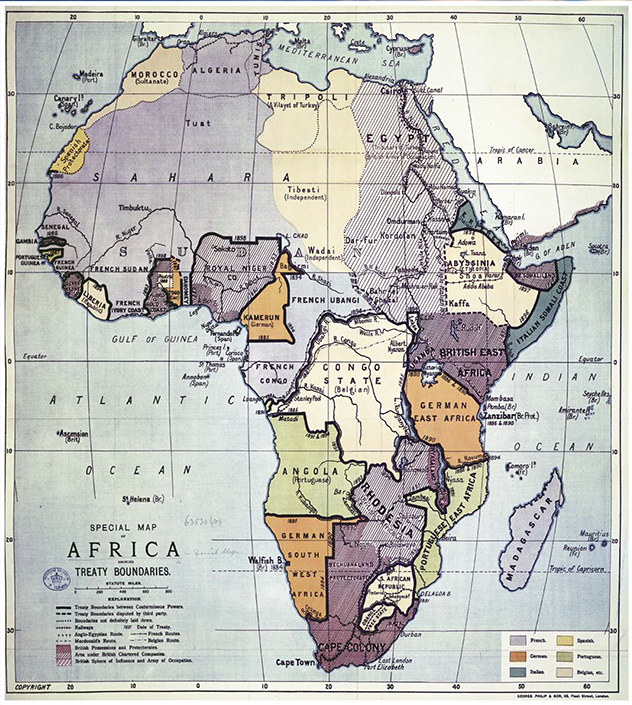

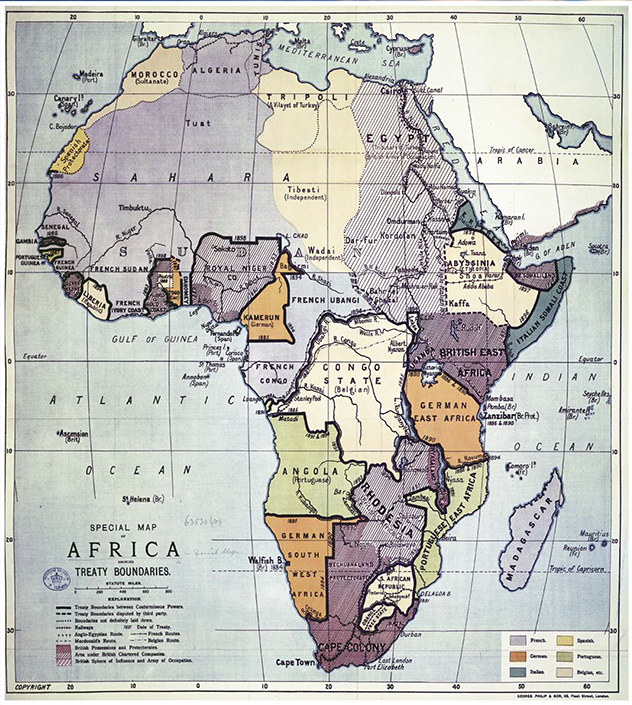

This map of Africa dates from 1891. You can see the borders that the European nations decided on and the lands they each claimed.

Slavery, though practiced in Africa itself and widespread in the ancient Mediterranean world, had nearly died out in medieval Europe. It was revived by the Portuguese in Prince Henrys time, beginning with the enslavement of Berbers in 1442. Portugal populated Cape Verde, Fernando Po (now Bioko), and So Tom largely with black slaves and took many to the home country, especially to the regions south of the Tagus River. African slaves were imported into Spains New World possessions in the early 16th century, as well as into the Portuguese possession of Brazil and, somewhat later, into the British colonies of North America. However, it was not until the development of sugar, cotton, and tobacco plantations in the Americas that the Atlantic slave trade reached huge proportions, exceeding any such earlier trade. The British became the major traders in slaves, although the French, the Dutch, and others also took part. African societies that had not participated in the slave trade prior to the European presence began to do so. Small African states that lay near the coast served as suppliers to the Europeans and grew into sizable empires because of their new wealth and power. Ashanti and Oyo in West Africa are examples. They supplied European merchants with slaves that they obtained through warfare with neighboring states.

In 1807 the British government declared the slave trade illegal and ordered British merchants to cease trading in slaves. States that had traded directly with the British were forced to find new ways to support themselves; Ashanti, for example, began to export kola nuts to its northern neighbors. A number of African societies put slaves to work in activities such as mining gold and raising peanuts, coconuts, sesame, and millet for the market. Other Africans continued to trade slaves with Europeans who did not accept Britains decree. The British navy patrolled the West African coast during the first half of the 19th century to enforce the abolition, but slave dealers moved their operations southward; even some slaves from East Africa were sent to the Americas. In many areas slavery was not abolished effectively until the Europeans established their colonial presence late in the 19th century. Until then, Europeans could not stop internal African slavery because they did not have any power or influence beyond the coast.

In the mid-19th century, the European colonial presence was confined to Dutch and British settlers in South Africa and to British and French military personnel in North Africa. The discovery of diamonds in South Africa and the opening of the Suez Canal, both in 1869, focused European attention on the continents economic and strategic importance. A scramble among European powers to claim African territories soon followed.

By the turn of the 20th century, the map of Africa looked like a gigantic jigsaw puzzle, with most of the boundary lines having been drawn in a sort of game of give-and-take played in the foreign offices of the leading European powers. The division of Africa, the last continent to be so carved up, was essentially a product of the new imperialism, vividly highlighting its essential featuresa notable speedup in colonial acquisitions and an increase in the number of colonial powers. In this respect, the timing and the pace of the scramble for Africa are especially noteworthy.