Contents

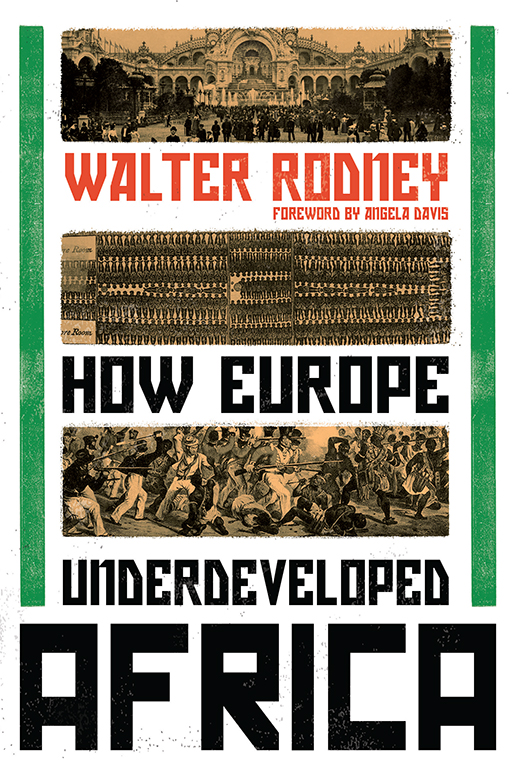

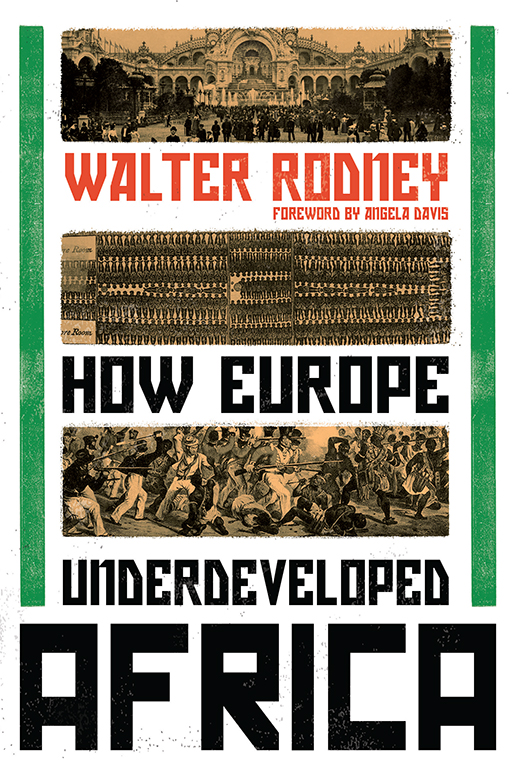

How Europe Underdeveloped Africa

How Europe

Underdeveloped

Africa

Walter Rodney

This edition published by Verso 2018

First published in the UK by Bogle-LOuverture Publications 1972

Walter Rodney 1972, Patricia Rodney 2018

Postscript A. M. Babu 1971, 2018

Foreword Angela Y. Davis 2018

Introduction Vincent Harding, William Strickland, and Robert Hill

1981, 2018

Frontispiece, original art by Brian Rodway.

Redesigned by Aajay Murphy.

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-118-8

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-119-5 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-120-1 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

To Pat, Muthoni, Mashaka

and the extended family

Contents

When Walter Rodney was assassinated in 1980 at the young age of thirty-eight, he had already accomplished what few scholars achieve during careers that extend considerably longer than his. The field of African history would never be the same after the publication of How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. At the same time, this meticulously researched analysis of the abiding repercussions of European colonialism on the continent of Africa has radicalized approaches to anti-racist activism throughout the world. In fact, the term scholar-activist acquires its most vigorous meaning when it is employed to capture the generative passion that links Walter Rodneys research to his determination to rid the planet of all of the outgrowths of colonialism and slavery. Almost forty years after his death, we certainly need such brilliant examples of what it means to be a resolute intellectual who recognizes that the ultimate significance of knowledge is its capacity to transform our social worlds.

We have learned from Walter Rodney, and those before and after him who have critically engaged with Marxism while developing historical analyses of colonialism and slavery, that challenging capitalisms deeply entrenched suppositions about human nature and progress is one of the most important tasks of theorists and activists who set out to dismantle structures and ideologies of racism. In refuting the argument that Africas subordination to Europe emanated from a natural propensity toward stagnation, Rodney also repudiates the ideological assumption that external intervention alone would be capable of provoking progress on the continent. Although colonization officially lasted only seventy years or so, which, as Rodney points out, was a relatively short period, it was during this period that colossal changes took place both in the capitalist world (i.e., in Europe and the United States) as well as in the emergent socialist world (especially in Russia and China). To mark time, he insists, or even to move slowly while others leap ahead is virtually equivalent to going backward (271). In How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Walter Rodney painstakingly argues that imperialism and the various processes that bolstered colonialism created impenetrable structural blockades to economic, and thus also, political and social progress on the continent. At the same time his argument is not meant to absolve Africans of the ultimate responsibility for development (34).

I feel extremely privileged to have been able to meet Walter Rodney during my first trip to the African continent in 1973. I mention this visit to Dar es Salaam because it took place shortly after the original publication of How Europe Underdeveloped Africa and because I witnessed firsthand for a brief period of time the revolutionary urgency generated within the scholarly and activist circles surrounding him. Not only did I have the opportunity to witness lectures and discussions he organized at the University of Dar es Salaam on the relation between African Liberation and global contestations to capitalism, but I also visited the training camps of the MPLA, where I met Agostinho Neto and the military cadre fighting the Portuguese Army. Walter Rodneys analyses reflected both a sober, well-reasoned historical investigation, shaped by Marxist categories and critiques, and a deep sense of the historical conjuncture defined by global revolutionary upheavals, especially by African Liberation struggles at that time.

Because he was such a methodical scholar, he did not ignore gender issues, even though he wrote without the benefit of the feminist vocabularies and frameworks of analysis that were later developed. Others have pointed out that he would have no doubt given greater emphasis to these questions had he been active at a later time. Nonetheless, at several strategic junctures in the text, Rodney addresses the role of gender, and he is careful to point out that under colonialism, African womens social, religious, constitutional, and political privileges and rights disappeared while the economic exploitation continued and was often intensified(275). He emphasizes that the impact of colonialism on labor in Africa redefined mens work as modern, while constituting womens work as traditional or backward. Therefore, the deterioration in the status of womens work was bound up with the consequent loss of the right to set indigenous standards of what work had merit and what did not (275).

At the time that How Europe Underdeveloped Africa was published, Black activismat least in the United Stateswas influenced not only by cultural nationalist notions of intrinsic female inferiority, often fallaciously attributed to African cultural practices, but also by officially sponsored attributions of a matriarchalin other words, defectivefamily structure to US Black communities (e.g. the 1965 Moynihan Report). This book was an important tool for those of us who were intent on contesting such essentialist notions of gender within Black radical movements of that era.

If Walter Rodneys scholarly and activist contributions exemplified what was most demanded at that particular historical momenthe was assassinated because he believed in the real possibility of radical political change, including in Guyana, his natal landhis ideas are even more valuable today at a time when capitalism has so forcibly asserted its permanency, and when once existing organized opposing forces (not only the socialist community of nations, but also the non-aligned nations) have been virtually eliminated. Those of us who refuse to concede that global capitalism represents the planets best future and that Africa and the former third world are destined to remain forever ensconced in the poverty of underdevelopment are confronted with this crucial question: how can we encourage radical critiques of capitalism as integral to struggles against racism as we also advance the recognition that we cannot envision the dismantling of capitalism as long as the structures of racism remain intact? In this sense, it is up to us to follow, expand upon, and deepen Walter Rodneys legacy.