Building Colonialism

Debates in Archaeology

Series editor: Richard Hodges

Against Cultural Property, John Carman

The Anthropology of Hunter Gatherers, Vicki Cummings

Archaeologies of Conflict, John Carman

Archaeology: The Conceptual Challenge, Timothy Insoll

Archaeology and International Development in Africa, Colin Breen and Daniel Rhodes

Archaeology and State Theory, Bruce Routledge

Archaeology and Text, John Moreland

Archaeology and the Pan-European Romanesque, Tadhg OKeeffe

Beyond Celts, Germans and Scythians, Peter S. Wells

Combat Archaeology, John Schofield

Debating the Archaeological Heritage, Robin Skeates

Early European Castles, Oliver H. Creighton

Early Islamic Syria, Alan Walmsley

Gerasa and the Decapolis, David Kennedy

Image and Response in Early Europe, Peter S. Wells

Indo-Roman Trade, Roberta Tomber

Loot, Legitimacy and Ownership, Colin Renfrew

Lost Civilization, James L. Boone

The Origins of the Civilization of Angkor, Charles F. W. Higham

The Origins of the English, Catherine Hills

Rethinking Wetland Archaeology, Robert Van de Noort and Aidan OSullivan

The Roman Countryside, Stephen Dyson

Shaky Ground, Elizabeth Marlowe

Shipwreck Archaeology of the Holy Land, Sean Kingsley

Social Evolution, Mark Pluciennik

State Formation in Early China, Li Liu & Xingcan Chen

Towns and Trade in the Age of Charlemagne, Richard Hodges

Vessels of Influence: China and the Birth of Porcelain in Medieval and Early Modern Japan, Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere

Villa to Village, Riccardo Francovich and Richard Hodges

The idea for the research contained in this book came about when I was working as an intern for the British Institute in Eastern Africa. Whilst travelling around Kenya and Tanzania working on various archaeological projects I became acutely aware of the lack of urban-centred archaeological research and a lack of engagement with the more recent past (an opinion later strengthened when carrying out research in Sudan). Many of the medium- to small-sized towns I visited contained centres of derelict and unused buildings dating from East Africas nineteenth-century colonial era. I began to wonder what the social and spatial implications of this was and formulated plans to design a research project that was based on the kind of Urban Landscape Analyses being carried out in the UK and Ireland, and link this with an anthropological social study of current attitudes of the towns inhabitants to these buildings and spaces. The relationship between archaeology and history is a much more transparent one within the commercial sector in the UK and Ireland, and I had accordingly brought this attitude to bear on the more academically led research I was witnessing. I saw no reason why the techniques of artefact, building, spatial and historical analyses used every day in the commercial sectors of Europe couldnt be adopted to highlight the existence of, and accordingly the need to conserve, the urban centres of Africas more recent past. The overall aim being to demonstrate to those who viewed Africas archaeology as being largely one of a prehistoric nature the value of such historic places both in research and potentially (if not already) to communities. Im happy to say that this book contains one half of the results of that ambition (the anthropological study of current attitudes requiring more time and greater ongoing research than could be mustered in this first instance), and hopefully goes some way to highlighting the need for research and conservation of these important places in East Africa.

The research was made possible by Colin Breen and the Centre for Maritime Archaeology at the University of Ulster and Paul Lane and Stephanie Wynn-Jones formerly of the British Institute in Eastern Africa. I was also graciously supported in kind by Ted Pollard, Joseph Matua, Mjema Elinaza and Mary Davies. Special thanks go to Stefan Sagrott for reproducing and designing the illustrations throughout the volume.

Thematically this book is constructed from a number of strands of research concerning social conflict, international development and theoretical approaches to identity formation at a national level. All of which have coalesced in the colonial encounters described herein. But beyond this, little can be said of my impartiality. Places and buildings were examined that were available to me via various funded and non-funded academic and non-academic routes, and political and theoretical stands have been taken that are purely and simply of my own creation based on my own innate bias. I have, in short, no one to blame but myself.

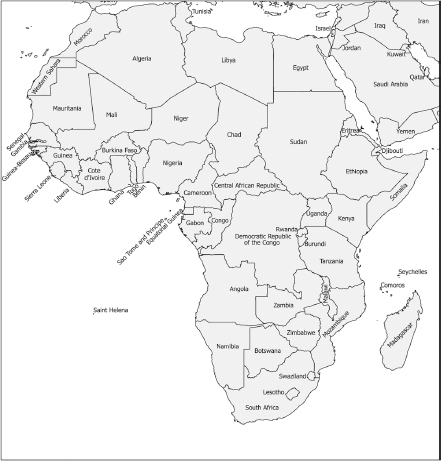

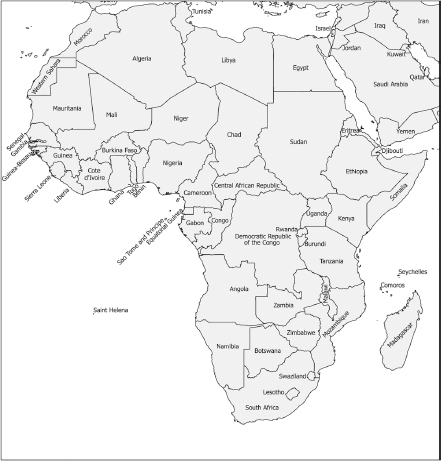

This short volume is intended to bring to the attention of the wider archaeological community the potential for the investigation of Africas more recent past. Less broadly than this it represents a call for consideration to be paid to some of East Africas neglected nineteenth-century urban heritage. It necessarily concentrates upon Tanzania and Kenya, as the towns within these states form not only the bulk of my research experience, but also the key entry points into Africa for many of the nineteenth-century colonial regimes which were to shape the destinies of the people of the continent. These towns include Mombasa (Kenya), Tanga, Pangani, Bagamoyo, Dar es Salaam, Kilwa Kivinje, Chole (United Republic of Tanzania) and Zanzibar (a semi-autonomous part of Tanzania under the Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar). The work looks at the remains of the physical impact of European interaction with the people and environments of nineteenth-century East Africa and compares these with examples of colonial approaches outside what was the British and German sphere of influence. It does this through the examination of European-built heritage and the ways European powers manipulated space within towns in order to control people and economies. It also looks at the importance of conserving this heritage as a tangible reminder of the impact nineteenth-century colonialism had on forming our contemporary opinion of, and life in, Africa (Figure 1).

Within this broad theme there are a number of interconnected aims. The main aim is to examine the role of the built environment as a tool of ideological expression within the colonial environment, and to look at how it may be possible to begin to decipher the intentions and impacts of Europeans in nineteenth-century East Africa from the structures they created. Secondly, I hope to demonstrate the possible ways in which archaeology can be used to address fundamental questions of social and political change in colonial regimes. In other words, how do the physical remains express the social impact that colonial activity had on people in the nineteenth century?

The impact of nineteenth-century European colonialism upon world cultures has been, and continues to be, undeniably profound. More and more in contemporary archaeology (and heritage studies), this impact is being recognized in the way we formulate our perception of the past. Whether we look at pre-colonial societies or colonial and post-colonial heritages it is all unavoidably (it can be argued) viewed through the lens of the European colonial influence. This recognition raises some interesting questions about the theoretical validity of a piece of work such as this one. As a piece of work which is in essence a study of European colonial activity from an unavoidably European perspective, the remainder of this first chapter is therefore intended to give an indication of the kinds of theoretical questions that underpin the ideas expressed throughout the rest of the book.