Ben Rawlence - The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth

Here you can read online Ben Rawlence - The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, year: 2022, publisher: St. Martins Publishing Group, genre: Children. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth

- Author:

- Publisher:St. Martins Publishing Group

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- City:New York

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ben Rawlence: author's other books

Who wrote The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To the trees and all living things that call the forest home

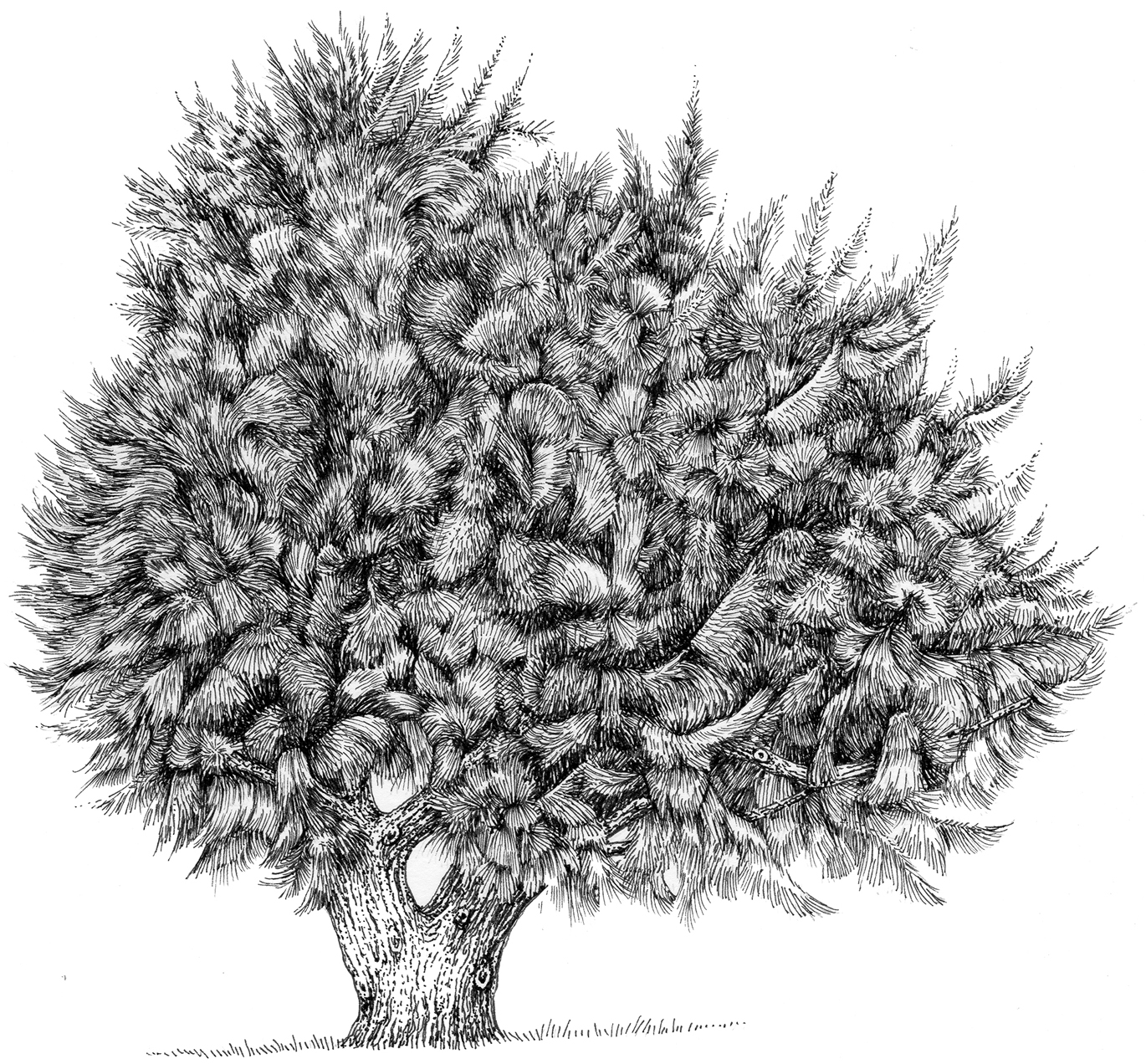

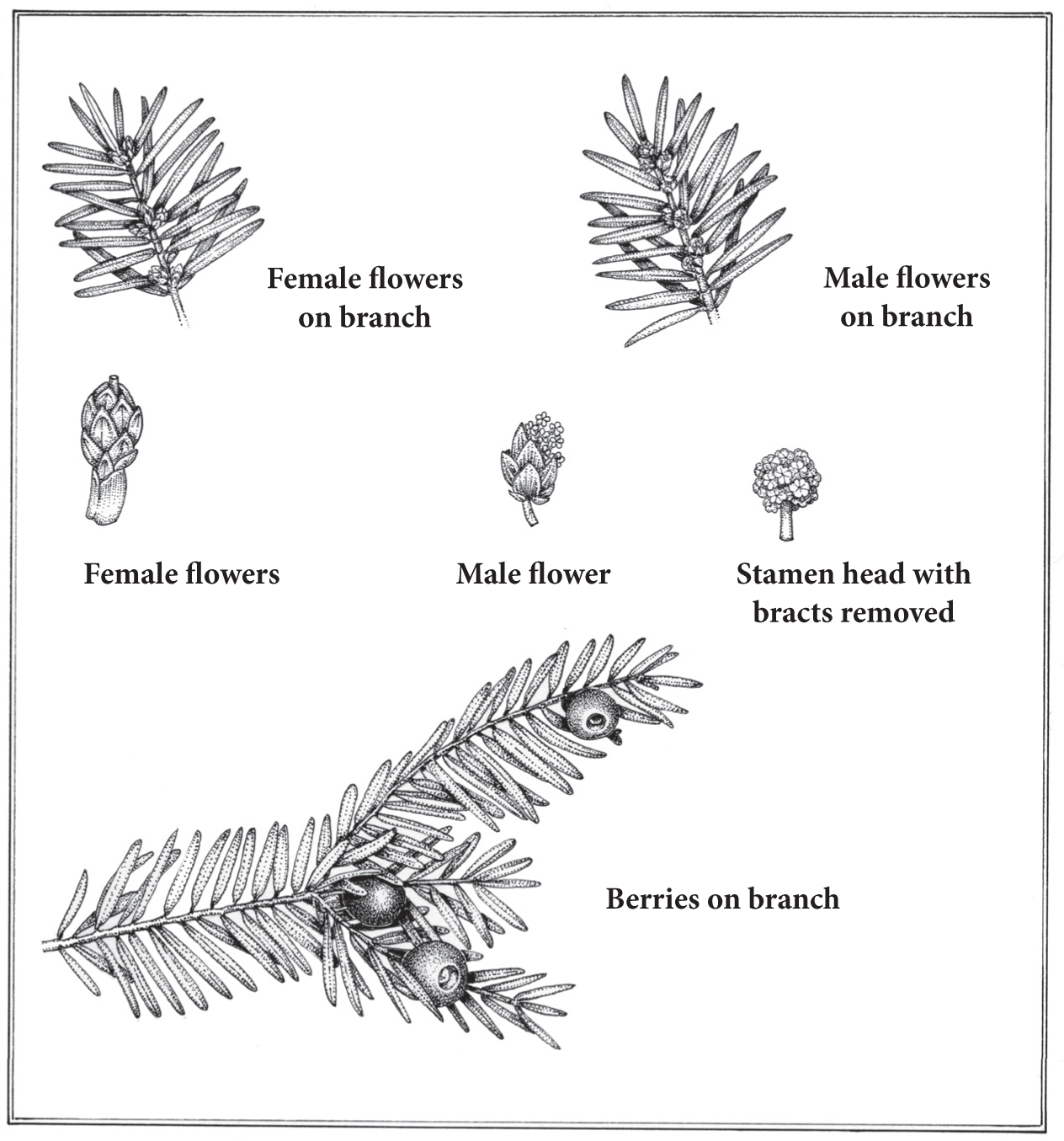

Taxus baccata, yew

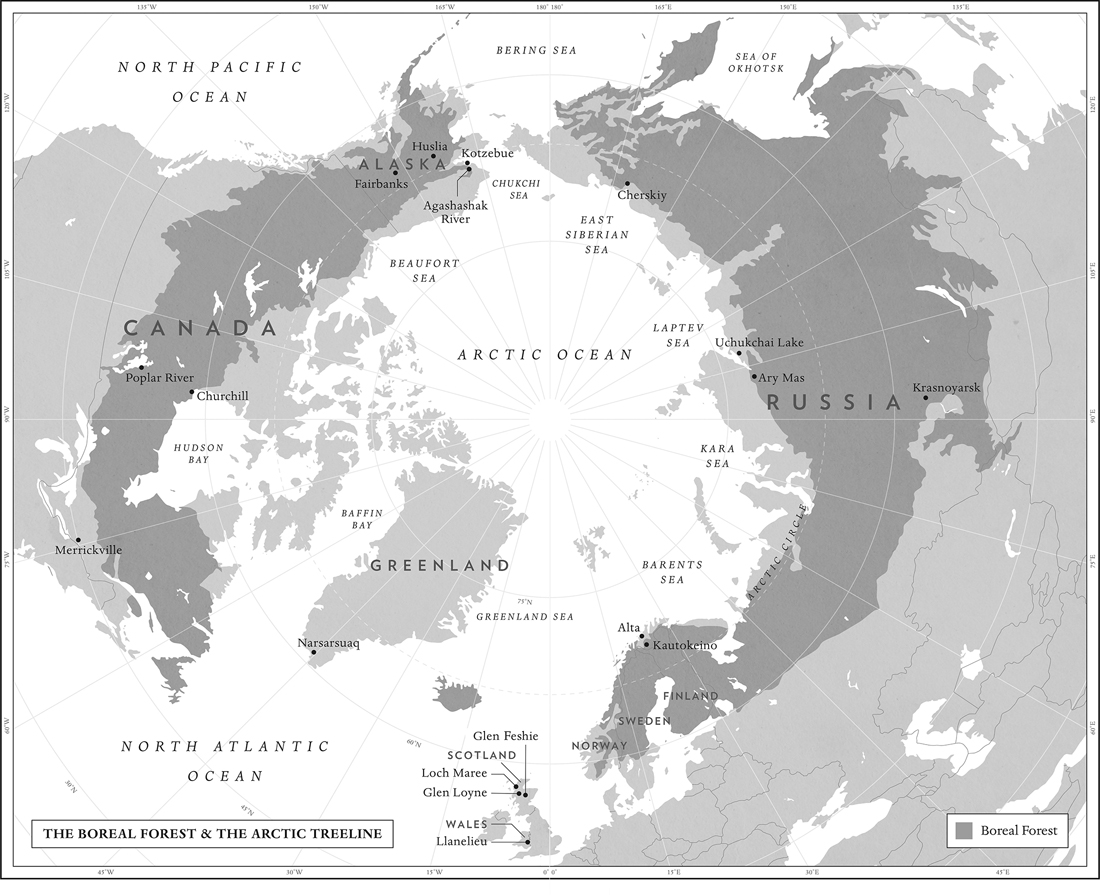

LLANELIEU, WALES: 52 00 01 N

Behind my house is a very large and very old tree. I never gave it much thought, a commonplace thing, a gnarled old tree by a churchyard, a typical Welsh scene. But lately I have found myself paying more attention to trees.

The tree in question is a yew, Taxus baccata. It stands on a mound several feet above the road, roots tightly gathered below the soil, bunched muscles under skin. The yews delicate evergreen needles resemble fine hair and they hang from great curved branches in an untidy fringe hiding a facea shy green man perhaps. To approach the trunk, you must duck your head beneath the swooping fringe and part the branches like heavy sacred curtains, as if venturing behind an altar. It is a mysterious refuge from the path only steps away, rich with the acid tang of evergreen, of life.

On the opposite bank of the path is another yew, slightly smaller but with the same smooth pinkish bark, furry and sticky in places. I follow its exposed roots bursting from the soil, snarling their way along the bank and under the path, entangling with those of its larger neighbor, forming one living structure. Upon closer inspection, the smaller tree is sporting bright red berries: she is female. The larger one, without fruits, is male. They are a handsome, imposing pair, but, try as I might, I cant find anyone who knows how old these ancient lovers are, nor how they got here.

Dating yew trees is notoriously hard. This is partly because there is no upper age limit. They grow rapidly in youth, steadily in middle age and can survive in senescence for an apparently unlimited period. Sometimes growth can stop and the tree can stand dormant for long periods, possibly centuries. Tree ring analysis fails with yews. Like cedars, they can grow from a low-hanging branch that has rooted in the soil, and shoots can sprout from stumps; left alone, a yew might be capable of regenerating itself forever. This was one of the things that made them sacred to the Celts. They worshipped the yew with its toxic red berries, pink flesh and copious sap precisely for its godlike attributes, its ability to bestow life and death and for its claim to immortality. The churchyard is circular, an indicator of a llana pre-Christian sacred site preceding the little Norman church. Yews are often found with llan. The old couple standing quietly above the stone circle, holding hands under the path for centuries if not millennia, might be the reason the village of Llanelieu is here at all.

Ancient trees are a source of wonder. Refugees from another era with a life cycle so much longer than human timescales. Their distribution and range is the result of incredibly long planetary cycles of geology, climate and evolution. The curious distribution of yews, for example, found only in the high mountains of Central Asia and scattered redoubts of northern Europe, suggests that it must once have been more widespread and is now a relict speciesthe remaining examples are outliers from a different epoch. This may be a consolation in moments of crisis, a reminder that our concerns are mere specks in the deep accumulated time of thousands upon thousands of tree rings. But now that humanity has upset the planetary systems of oceans, forests, winds and currents, the balance of gases in water and air that gave rise to our species, their consolations are in question. Trees no longer offer comfort, but warning.

It is our complacent attitude to time that is the first casualty of global warming: millennia have become moments. These days I cannot look at the mountain, the forest or the field without feeling the ground tremble in both anticipation and memory. Our best guide to the coming uncertainty is history: geology, glaciology and dendrochronologythe studies of rocks, ice and trees. Thus, the past and the future are made immanent, time has become slippery, and a walk in the hills can make you dizzy. Suddenly I see trees everywhere: where they are not, where they have been, where they should be. It is a way of looking at the landscape outside of time, as people closer to the earth have always done. And, seen as such, the view looks wrong. The clean, green lines of the Black Mountains that rise above the church and the village now appear to me a tragic desert, a monument to a geological epoch of collective human folly.

These hills are the border between England and Wales. The crossing of this line first by the Romans, then later by the Danes and then the medieval kings of England marked the beginning of a movement which is finally reaching its endgame in the last great vestiges of wildwood on the planet: the tropical Amazon and the subarctic boreal. The Romans, Danes and the nobles of England were in search of natural resources, principally timber. The colonization of Wales was the first expression of an economic system founded on overreach: having exceeded the limits of what their own environment could sustain, early mercantilists applied force to acquire tribute and resources elsewhere. Empire, whether British, Viking, Roman or otherwise, is by definition overreach. And colonialism, capitalism and white supremacy share a common, perverse philosophy: limits on some humans freedom of action are seen as an affront to the principle of freedom itself. The exact opposite of the coevolutionary dynamic of the forest.

Once upon a time, these hills were covered in trees. All thats left now is a patchy ecosystem called ffridd or coedcaehawthorn, scrub and bracken mixed with broadleavesa transition zone between lowland and upland habitats. The peat on the top is testament to the forest that once was. But that was before our neolithic ancestors cleared the forest for grazing and fuel, and before our later penchant for deer, grouse and, of course, sheep. Before the trees, however, before there was any covering on the rock at all, there was ice.

The last ice age ended ten thousand years ago, mere seconds on the planetary clock. The old yews of Llanelieu could be the grandchildren or even the children of one of the first trees that took root as the ice retreated. Conifers like yews have evolved specifically in relation to the cycles of ice. They thrive in marginal environments, in tough soil with limited nutrition. This is the process of the treeline at work. For the treeline is not really a line at all.

The fact that in modern usage the term treeline has come to mean a fixed line on a map indicating the growing limit of trees is simply evidence of the very narrow time horizons of humans, and of how much we have come to take our current habitat for granted. In fact, the growing conditions for trees whether limited by altitude (up a mountainside) or latitude (toward the North Pole), are only as certain as the environment that produces them: the availability of soil, nutrients, light, carbon dioxide and warmth. For a couple of millennia these climatic conditions have remained remarkably constant, but over longer timescales tiny changes in global temperature have meant that the treeline has always been a moving target.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth»

Look at similar books to The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.