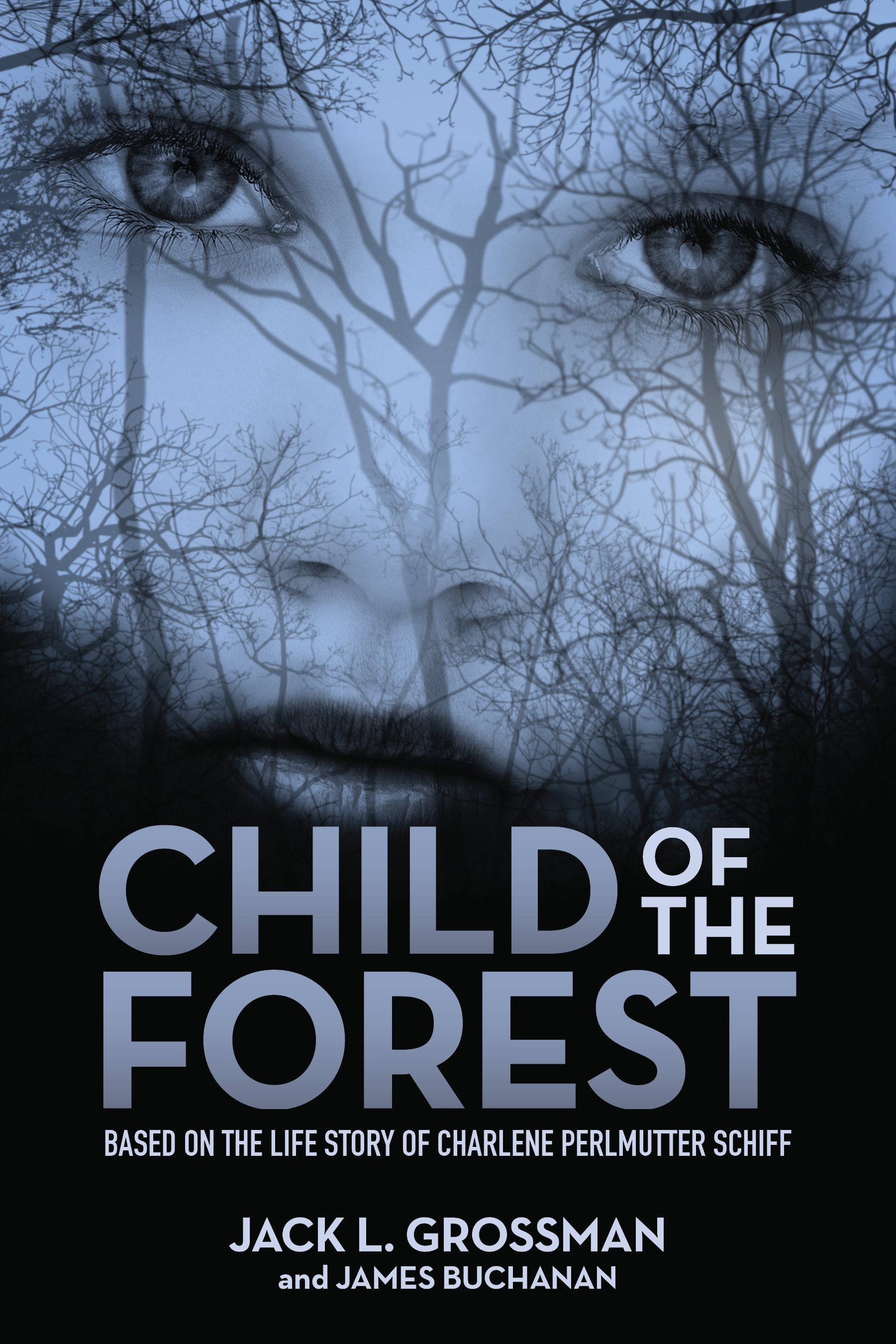

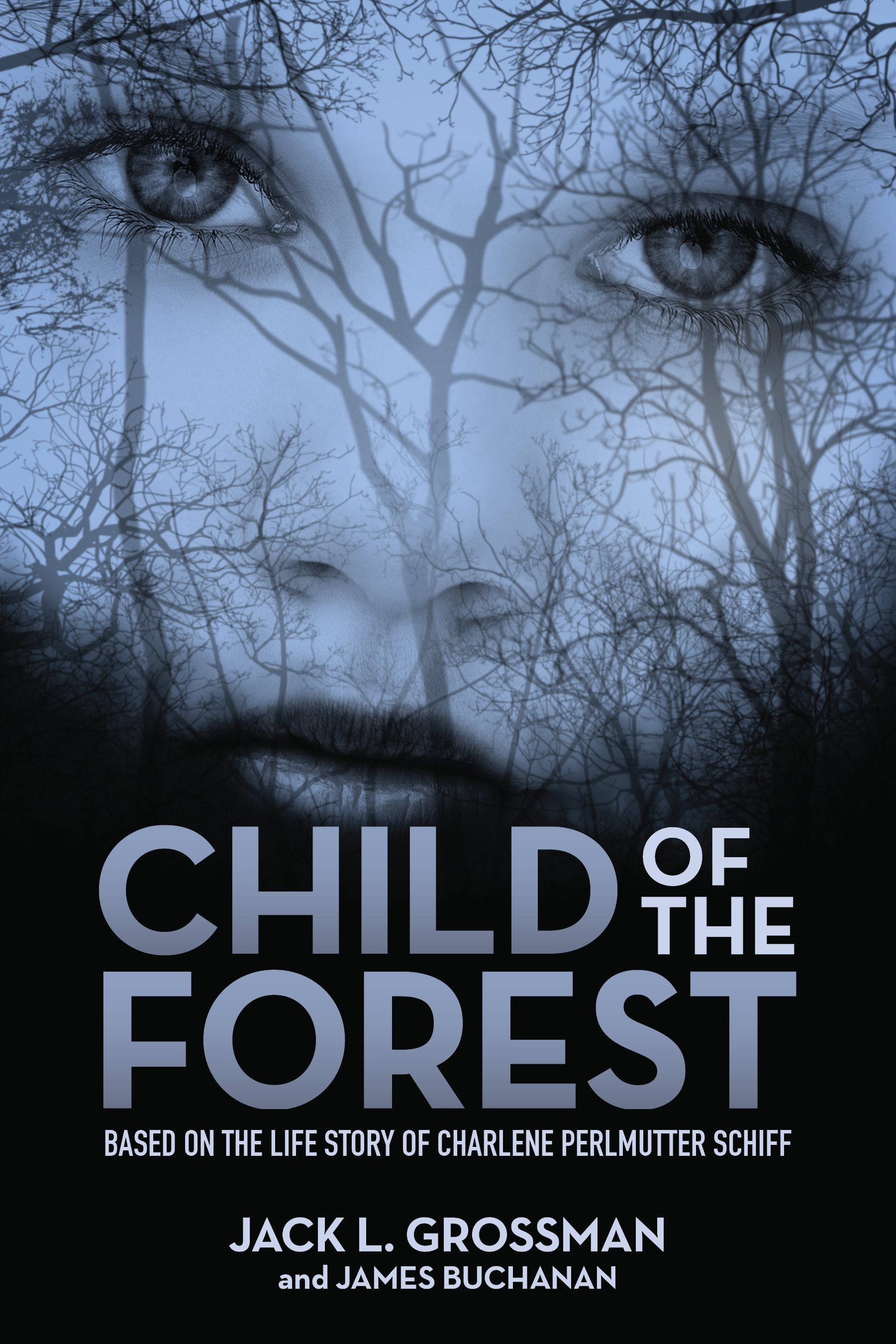

Child of the Forest

By Jack Grossman and James Buchanan

Copyright 2018 by Jack Grossman. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from Jack Grossman, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For permissions requests, please contact Jack Grossman at jack@jackgrossman.com.

Designed, produced, and published by SPARK Publications, SPARKpublications.com

Charlotte, NC

Cover Design by Jack Grossman and SPARK Publications.

This story is based on the true life story of Charlene Perlmutter Schiff and recreates events, locations, and conversations to the best of her recollection. Individuals names may have been changed in instances where Charlene could not recall actual names of people she met in passing. Any similarity between the fictitious names with actual names or characters is purely coincidental.

Printed in the United States of America.

Hardcover, October 2018, ISBN: 978-1-943070-48-0

Paperback, October 2018, ISBN: 978-1-943070-49-7

E-book, October 2018, ISBN: 978-1-943070-50-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018956806

Dedication

To all of the precious, innocent souls who perished in or survived the Holocaust. NEVER AGAIN.

To the many people, including my wife, Kristie, and our daughters, who believed in me and supported me throughout this journey.

To my grandparents, parents, and the many relatives and friends, living and deceased, whom I love deeply.

And to my dear friend Charlene, the most amazing person I ever met. Your kind soul and gentle spirit will forever live in me.

Table of Contents

Foreword

O n Memorial Day of 2006, I visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum for the third time in four years. It was a day I will never forget. The field trip I helped chaperone arrived at the break of dawn in Washington, D.C., by bus from Charlotte, North Carolina. Just like my previous trips, we started the day with a prayer service at the Vietnam War Memorial as silhouettes in the background laid memorials at the base of the wall while others transcribed names from the wall onto paper. It was a perfect prelude to what I was about to experience.

I was accompanied by my youngest daughter, a bus load of other twelve-year-old children, and a few other chaperones. After the short and reverent prayer service, we were off to the Holocaust Memorial, and I prepared mentally for the familiar, somber experience. I went expecting to feel the same level of deep sadness that I felt on my previous trips, but I did not expect to be so profoundly moved. My view of life was forever altered when I heard a story about a young girl and her experiences during the Nazi invasion of her small town in Eastern Poland during the early 1940s. The more I listened to her story, the more I questioned whether I heard it correctly. I kept asking myself, Did I really just hear that?

Charlene was known as Shulamit Perlmutter but lovingly called Musia (pronounced Moosha) by everyone who knew her. Her story was so moving it literally embedded into my subconscious. I could not run from its presence. In fact, for the remainder of the day and the next day traveling home, I couldnt get it out of my head. I kept repeating to myself, Did I hear her story correctly? Did this really happen?

Upon arriving home, I greeted my family and, without hesitation, went immediately to the computer. I searched the Internet hoping to find a book or movie about this young girl and her experiences during one of humanitys darkest times. I kept thinking how she must have felt and if I would be as brave. I so badly wanted to share this story with my family, but I also wanted to confirm that I heard it correctly; I wanted answers to my burning questions. I searched and searched the Internet but to no avail. I thought, How can this be? I had just heard the most compelling story of my entire life, and it has not been documented in a book or film for others to experience? It was right then and there that I looked up to my wife from my chair and said, I am going to make sure Charlenes story is told to the world whatever it takes.

And yes, I heard her story correctly. And yes, it really did happen, but it was even more incredible than I first thought and more compelling than I could ever imagine.

Jack Grossman

September 2018

North Carolina

Hope is a fiction. Its a dream that tomorrow will be different, or some miracle will happen to save you. Its not sufficient; its not enough to keep you alive in the ghetto, the camps. When a person is drowning, and they reach for air, its not hope that propels that fight. The drive to live is what pushes us toward life, but its stronger in some and can make the difference between life and death. Why stronger in some? Its always love. Love is what allows us to keep our humanity and know that someone needs us to survive.

Estelle Laughlin, Holocaust survivor

and personal friend of Shulamit Musia Perlmutter

Liquidation

O ur last morning in the ghetto, Mama was gentle as she woke me.

Musia, darling, time for us to go.

She brushed a wisp of hair from my eyes. Her trembling fingers lingered against my skin.

Come, you need to open your eyes, neshomeleh .

I breached the surface but let myself drift back into the warmth of somnolent waters.

My neshomeleh, you must wake up. We have to go. The softness in her voice belied the strain on Mamas nerves. Please, Musia.

I opened my eyes, and in one, deep breath the acidic odor of human rot burned my nostrils, eyes, and throat. Mamas face hung above me like a dimmed, emaciated moon, her eyes smudged by exhaustion.

Musia, do you remember how to get to the Voitenkos? she whispered.

Yes, Mama.

They live in Skobelka.

I know, Mama.

When we cross the river, we walk across the field until we reach the road to Skobelka.

I know, I know, Mama; youve told me so many times

Musia, please, whisper. Her eyes wandered toward Mrs. Joselewicz, sitting on a bed of wood laths torn from a wall and supported by scavenged bricks. At forty, Mrs. Joselewicz sallow, jaundiced face and withdrawn eyes made her look like an old woman.

Mama continued. You must not forget

I remember their farm from before

because if you lose me, you will have to find the Voitenkos on your own. Mamas eyes welled.

I know, Mama. Im twelve, not a little girl.

She took a deep breath and seemed to regain some strength. Promise me you will go to the Voitenkos.

I sat up and looked into Mamas eyes. I promise.

We have to go now. She steadied herself with one arm and stood. Her dress swayed as if draped on a wooden clothes hanger.

An aching nausea roused itself in me. I held my arms against my belly to soothe the pain and hunger, but they were little comfort.

Put your clothes on like I told you, Mama said as she wrapped a sweater around her body. Do you remember?

Yes, Mama.

And wear your winter shoes.

Its August, Mama. Theyll be too hot.

Mama looked to Mrs. Joselewicz, who was taking an interest in our conversation. Mrs. Cukier looked up as well. She lay on her own bed of lath and brick, cradling her wheezing five-year-old daughter Ania to her withered bosom. Anias body was bony and pitted, head shaved and flecked by abscesses that wept rancid yellow pus where lice had burrowed into her skin. Florid blooms of reddened skin covered the rest of her body. Her eyes were glassy and impassive, mouth fixed in a gaping, oblong O. She was more cadaver than child.