Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the people who took the time to share their stories with me in difficult circumstances, especially the members of the Concerned Women, the Stakeholders, and the Vision , whose grace and public-spiritedness in the face of crisis continue to inspire me. I am grateful also to my fellow researchers who worked in Ghana and Liberia and generously shared their insights: Anthony Nimley and Jelbeh Johnson, who contributed valued research assistance; and Samuel Agblorti, Susanne Tete, Jeff Crisp, Kaisa Akvist, Akosua Darkwah, Drte Rompel, Guy Threlfo, and Tehila Sagy.

This book owes much to the support of my colleagues and friends at the University of Connecticuts Research Program on Humanitarianism, Human Rights Institute, and Department of Sociology. Cathy Schlund-Vials read the entire manuscript at a crucial juncture and gave valuable guidance. Eleni Coundouriotis, Kathy Libal, Richard Wilson, Emma Gilligan, Gaye Tuchman, Manisha Desai, and Davita Glasberg read and offered insights on several selections. Susan Silbey, Sandy Levitsky, Bandana Purkayastha and Nancy Naples offered practical and professional support throughout. Chapters 2 and 3 benefited greatly from exchanges with Claudio Benzecry, Hallie Liberto, Jeremy Pais, Mike Wallace, Shauna Morimoto, Alice Kang, and Kristy Kelly. I presented earlier versions of Chapter 5 at the University of Mary Washington and the Law and Society Conference and received valuable feedback from Hui-Jung Kim and Mark Massoud. An earlier version of Chapter 6 received valuable feedback from Andreas Wimmer, Ann Swidler, Silvia Pasquetti, and others at the 2010 Junior Theorists Symposium. The conclusion benefited enormously from debates on the alternatives to refugee camps that I have participated in with Galya Ruffer, Zachary Lomo, Michael Kagan, Paula Banerjee, and others on the Sanctuary without Refugee Camps panel series at the Human Rights Institute 10th Anniversary Conference and the 2014 International Association for the Study of Forced Migration Conference. An earlier version of the Methodological Appendix received valuable feedback from Anna-Marie Marshall, Mark Suchman, Elizabeth Mertz, and others at the 2008 Midwest Law and Society Retreat. In its earlier life, this project benefited greatly from the support of my mentors, Myra Marx Ferree, Erik Wright, AiIi Tripp, Dave Trubek, Pam Oliver, and Ivan Ermakoff. Now, as it nears completion, I benefited greatly from advice and feedback from Roger Haydon, my editor at Cornell University Press, and the anonymous reviewers.

This work was supported by the Charlotte Newcombe Foundation, the National Science Foundation (0719733), the University of Connecticuts Large Faculty Grant, and the Human Rights Institutes Faculty Fellowship and Faculty Research Grant.

Portions of the introduction and Chapter 2 were published in Sociological Forum 29 (2014): 774800. Portions of Chapter 4 were published in Journal of Refugee Studies 25 (2012): 257281.

Introduction

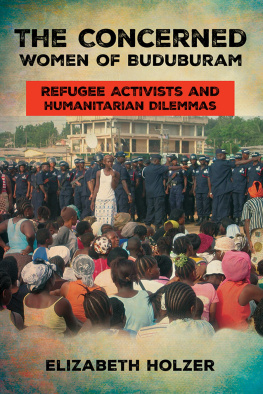

The Midnight Hour in This Refugee Crisis

Jayboy go inside! My neighbor shouted to her thirteen-year-old son. Startled by the panic in her voice, I stumbled outside to see her. It was a Saturday morning in the Buduburam Refugee Camp in Ghana, West Africa. I had been here for eight months studying camp politics, living with about thirty-five thousand refugees from the Liberian civil war, a few hundred refugees from Sierra Leone and Cte DIvoire, and their Ghanaian neighbors.

Across a dirt field where the kids usually played football, behind an evangelical church at the edge of the camp, I could see three men, running. Whats happening? I asked my neighbors crowded in the compound yard. Police had come for men, they told me. I noticed that no men stood among my neighbors.

The police had come to end protests by refugee women that had started five months ago. It was a gut-wrenching shockthey were peaceful protests, I thought. And what men? There were no men on the protest field.

I left the compound and headed to the field near the entrance of the camp where the protesters had been gathering for the past month and a half. I witnessed the confusion and disorder of the raid through a lightheaded haze of disbelief. Not far from my compound, I stopped to talk with a woman crying in her yard. We locked the door and they bust the door, they break our door, she said, pointing to the thin wooden door now propped in a corner of the room. Then he went in the bathroom, and they bust the bathroom door, and they went, and they got him from there with force, no slipper on his feet, we were here crying; they were carrying him. Beating him, a neighbor interjected. Why this man? The makeshift house was not near the protest field. Did he go near there? I asked. He was here, the woman said emphatically. He always here selling the water. It was not uncommon to see people selling buckets of water for washing or small sachets of drinking water in camp. Its because of the noisethat what cause him to come in, the neighbor clarified. There was noise around, people were running, so he got afraid. That how he took it upon himself to come in. And before coming in, I think they spotted him coming in.

Near the camps entrance, police buses still stood in the field, and an armored truck and dark police jeeps were parked across the road. The officers were wearing riot gear or nondescript white shirts and black pants, so I knew they must have come from the capital. Why are the men being arrested? I asked a young policewoman. I dont know, she said. Who is in charge? I asked, and she waved vaguely toward the taxi stand. I approached a man holding a megaphone, dressed in black. What are these men being arrested for? He kept walking, acknowledging my question with a sharp downward cut of his hand.

On the field, it was chaosa few vivid images amid a blur of movement and noise. A young woman ran, dragging a toddler away from the protest field by the arm. The tiny girl glided through the air like a ballet dancer, her feet barely skimming across the ground. Wait! the girl cried in a teary voice, her sandal slipping off as she stumbled. Sorry, sorry, the woman said, pausing to pick up the sandal and slide it on the girls foot before taking off again. A small group of police officers dragged a middle-aged man, women swarming around them, entreating the police to release him. The officers huddled around the man they carried. They walked past the buses, crossing the road at the end of the field, cars passing on the heavily trafficked highway. A woman bolted from the crowd, sobbing as she threw herself to her knees on the road. A fast-approaching truck halted a few feet from her, and another woman dragged her from the road. She broke from the arms of her friend, grabbed a stone from the road, and chucked it at the rear officer; an adolescent girl standing with a group of children at the roadside threw another stone, and the other children followed. Stones bouncing off his riot gear, the officer fumbled with a canister on his belt, turned to the woman and the girls, paused, and then set the canister back down and continued walking to the dark SUV. Where are you taking him? I asked. What is he charged with? You can inquire in the Accra central office, an officer told me. This is not a safe place, my friend said to me, nodding to the group of women and children who were growing progressively more enraged. Her own husband had been taken as he left the house to brush his teeth that morning. There was no running water in the camp, so most people washed their faces and spat out the toothpaste in their yards.