Baltimores Mansion

National Bestseller

Winner of the Charles Taylor Prize for Literary Non-Fiction Shortlisted for the 1999 Governor Generals Award for Non-Fiction

A love letter not only to [Johnstons] homeland, but to his father, a staunch anti-Confederate unable to relinquish his vision of what Newfoundland once was and could have been. Thanks to Johnstons powers of evocation, the reader is able to share a fleeting glimpse of that vision.

Lynn Coady, Chatelaine

A humane and winning book, passionate and yet careful in its articulation of the old story of fathers and sons, poetic in its narrative freedom, but very personal as well.

The Gazette (Montreal)

This is an absorbing, sometimes amusing, often moving read, carried strongly by Mr. Johnstons fine prose.

Ottawa Citizen

A great companion to The Colony of Unrequited Dreams. The familys political fury gives zip to Johnstons decision to write about Smallwood and both books reveal the frightening grandeur of the land.

The Hamilton Spectator

Baltimores Mansion is an unusual and vibrant book, a fine tribute to the island that has been such a formidable part of the Johnston and other clans, a land whose influence is hard to define but is evident in the way one views the world.

The Edmonton Journal

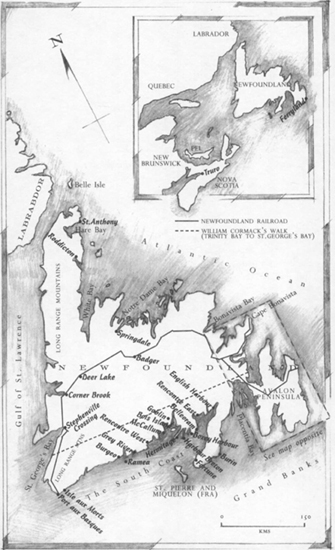

Deftly weaving family stories, political history and Arthurian legend, Johnston reflects on the tragic destiny of the Avalon, a community that once believed it could be an islandand a nationunto itself.

Elm Street

Easily one of the best memoirs ever published in this country.

The Record (Kitchener-Waterloo)

[A] beautifully wovencollection of memories taken intact and replayed so clearly the reader becomes an intimate bystander. Long after the book is put down the images will continue to swirl within easy grasp.

New Brunswick Telegraph Journal

Also by Wayne Johnston

The Story of Bobby OMalley

The Time of Their Lives

The Divine Ryans

Human Amusements

The Colony of Unrequited Dreams

For the Johnstons of Ferryland

For the CallanansLaus, Cindy, Tim and Joeyof St. Johns

The Forge hath been finished this five weekes wee have prospered to the admiration of all beholders. All things succeed beyond my expectation.

From a letter by Captain Edward Wynne, Governor of the Colony of Ferryland, reporting on the progress of Baltimores mansion, to the colonys patron, Lord Baltimore, who took residence in the spring of 1627.

Ferryland, July 28, 1622

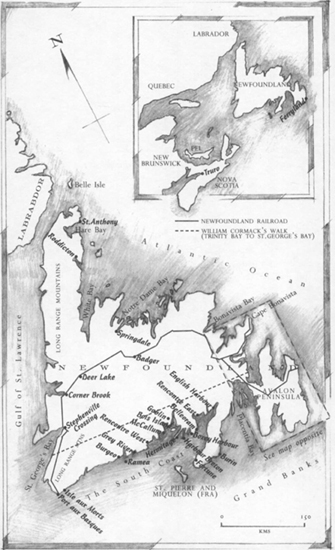

I AM FOREBORN of spud runts who fled the famines of Ireland in the 1830s, not a man or woman among them more than five foot two, leaving behind a life of beggarment and setting sail for what since Malory were called the Happy Isles to take up unadvertised positions as servants in the underclass of Newfoundland.

Having worked off their indenture, they who had been sea-fearing farmers became seafaring fishermen and learned some truck-augmenting trade or craft that they practised during the part of the year or day when they could not fish.

Their names.

In reverse order: Johnston. Johnson. Jonson. Jenson MacKeown. Mac in Gaelic meaning son and Keown John.

M Y FATHER GREW up in a house that was blessed with water from an iceberg. A picture of that iceberg hung on the walls in the front rooms of the many houses I grew up in. It was a blown-up photograph that yellowed gradually with age until we could barely make it out. My grandmother, Nan Johnston, said the proper name for the iceberg was Our Lady of the Fjords, but we called it the Virgin Berg.

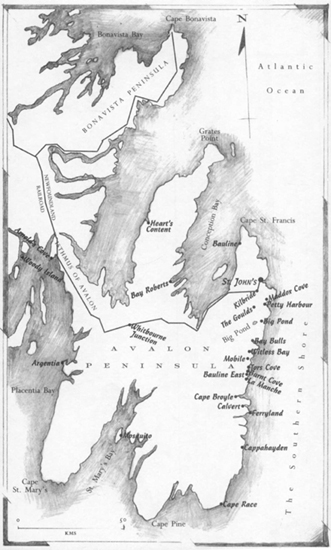

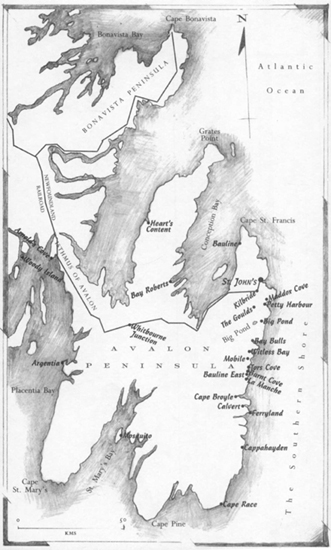

In 1905, on June 24, the feast day of St. John the Baptist and the day in 1497 of John Cabots landfall at Cape Bonavista and discovery of Newfoundland, an iceberg hundreds of feet high and bearing an undeniable likeness to the Blessed Virgin Mary appeared off St. Johns harbour. As word of the apparition spread, thousands of people flocked to Signal Hill to get a glimpse of it. An ever-growing flotilla of fishing boats escorted it along the southern shore as it passed Petty Harbour, Bay Bulls, Tors Cove, Ferryland, where my fathers grandparents and his father, Charlie, who was twelve, saw it from a rise of land known as the Gaze.

At first the islands blocked their view and all they could see was the profile of the Virgin. But when it cleared Bois Island, they saw the iceberg whole. It resembled Mary in everything but colour. Marys colours were blue and white, but the Virgin Berg was uniformly white, a startling white in the sunlight against the blue-green backdrop of the sea. Marys cowl and shawl and robes were all one colour, the same colour as her face and hands, each feature distinguishable by shape alone. Charlie imagined that, under the water, was the marble pedestal, with its network of veins and cracks. Mary rode without one on the water and there did not extend outwards from her base the usual lighter shade of sea-green sunken ice.

The ice was enfolded like layers of garment that bunched about her feet. Long drapings of ice hung from her arms, which were crossed below her neck, and her head was tilted down as in statues to meet in love and modesty the gaze of supplicants below.

Charlies mother fell to her knees, and then his father fell to his. Though he wanted to run up the hill to get a better look at the Virgin as some friends of his were doing, his parents made him kneel beside them. His mother reached up and, putting her hand on his shoulder, pulled him down. A convoy of full-masted schooners trailed out behind the iceberg like the tail of some massive kite. It was surrounded at the base by smaller vessels, fishing boats, traps, skiffs, punts. His mother said the Hail Mary over and over and blessed herself repeatedly, while his father stared as though witnessing some end-of-the-world-heralding event, some sight foretold by prophets in the last book of the Bible. Charlie was terrified by the look on his fathers face and had to fight back the urge to cry. Everywhere, at staggered heights on the Gaze, people knelt, some side-on to keep their balance, others to avert their eyes, as if to look for too long on such a sight would be a sacrilege.

A man none of them knew climbed the hill frantically, lugging his camera, which he assembled with shaking hands, trying to balance the tripod, propping up one leg of it with stones. He crouched under his blanket and held above his head a periscope-like box which, with a flash and a puff of foul-smelling yellow smoke, exploded, the mechanism confounded by the Virgin, Charlie thought, until days later when he saw the picture in the Daily