Y ou cannot not know history.

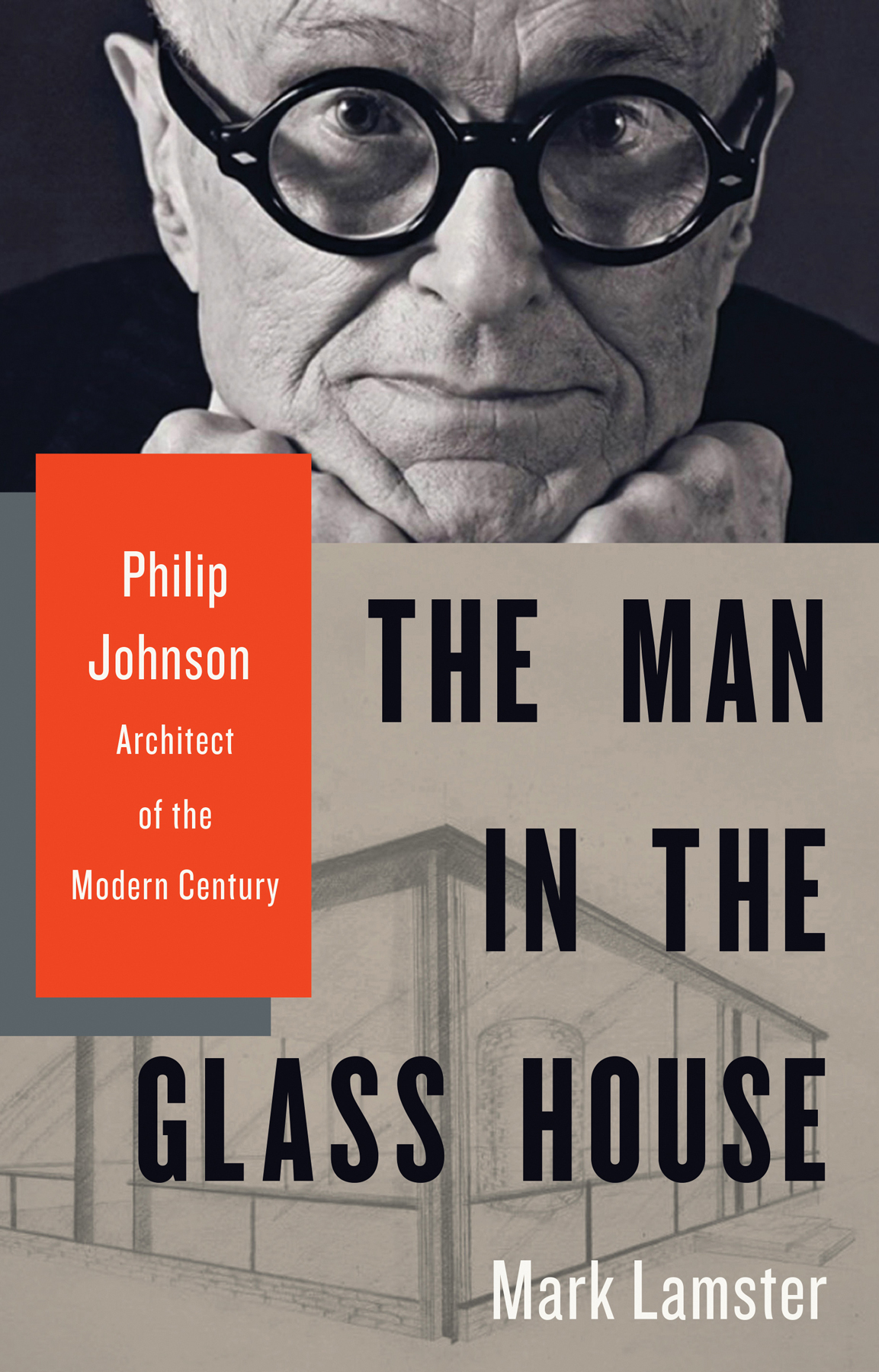

Philip Johnson issued that famous maxim in 1959, and though he was talking about architectural tradition, he could just as well have been speaking about his own rich life, which was then barely past its halfway point. That life began in 1906 and ended in 2005, and he spent just about all of the ninety-eight years in between stirring up trouble.

There is hardly a city in America that is not gracedor fouledby a building with Johnsons name on it, and often more than one. He craved attention, and made himself into a genuine celebrity. He was the architect of the imagination, a familiar face in his owl-frame glasses, a debonair, self-deprecating wit with a quip for every occasion.

His story, however, is much more than one of a charismatic man and his uneven architecture. Johnson lived the American century, and his story mirrored the nations epic trajectory in that time. It opened with the highest aspirations and ambitions, embracing the possibilities of a modern world, yet concluded by abetting the accumulation of vast power and influence by a select few. His story, like the American story, was one of darkness as much as light; a story of inequity and bigotry, of the perils of cynicism, of human weakness and venality, of rampant corporatism, of the collapse of wealth and authority into the hands of a plutocratic class. Philip Johnson began his career proselytizing the public in the name of modern design. He finished it building for Donald Trump.

We cannot not know Philip Johnsons history because it is our historylike it or not. His dozens of works range in quality from the nadir of grim opportunism to the apex of civic and architectural achievement, but either way they shape our skylines, our streetscapes, and our daily lives.

Johnsons buildings are ubiquitous, but his influence far exceeds their mere presence. He was a shaper not just of individual structures or even of cities, but of American culture. When his interest first turned to architecture as a young man in the 1920s, modernism was an esoteric movement confined mostly to industry, social progressivism, and the occasional luxury residence. By the time of his death, the modern, with its sharp forms and sharp materials, was the defining language of the American city, the vernacular of business, and the default aesthetic of the avant-garde and the cultural aristocracy. He was not fully responsible for that shift, but he played an instrumental part in it.

His career began not as an architect but as a curator and a critic. Johnson was the founding director of the architecture department of the Museum of Modern Art, and one of its most important patrons. His gifts of painting and sculptureworks by Jasper Johns, Paul Klee, Roy Lichtenstein, Mark Rothko, Oskar Schlemmer, Andy Warholdefine that institution and its narrative of twentieth-century art.

But it was in architecture and design that Johnson exerted greatest influence. His landmark exhibitions established the way design is presented and understood; that both everyday objects and grand works of architecture are worthy of veneration. More critically, he used his platform at the museum to promote a controversial vision of what modern architecture could and should bea modernity that was about form and style rather than the values that good design could promote: affordable, healthy, and environmentally sensitive building and planning that edified the private and public realms. When he tired of modernism he ushered in its rejoinder, postmodernism, and when he saw that as a dead end he reframed the field once again.

Johnson craved the attention that came with these reversals. He had a Barnumesque gift for publicity, and as with Barnum the principal beneficiary of his mythmaking was himself. Johnson, more than anyone, was responsible for the celebrity-driven practicestarchitecturethat came to dominate the profession at the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first. Through it all, he was a kingmaker, promoting the architects he favored and casting those he disdained into the wilderness.

He was controversial because he was happy to reverse himself, to lean in to his own hypocrisy, to occupy multiple positions even if they were diametrically opposed. Johnson was a historicist who championed the new, an elitist who was a populist, a genius without originality, a gossip who was an intellectual, an opportunist who was a utopian, a man of endless generosity who could be casually, crushingly cruel. For nearly a century, he had inhabited all of these oppositions, and countless others, concentrating in himself all of the contradictions and paradoxes of America and the century in which he lived. Not coincidentally, he was among the most loved and loathed figures in American culture. Many, somehow, loved and loathed him at once. Such was his strange charisma.

Johnson played to the image that he made of himself, especially in his later years: an avuncular, self-deprecating figure in a well-tailored suit. It was a long-practiced act that shielded him from criticism, suggesting that he was a harmless old wit, blameless for past transgressions. There were many of those, and not just sins of architecture. What he wished most to expunge from memory were his prodigal years in the 1930s when he launched himself as a virulently anti-Semitic fascist political leader, a would-be American Hitler, and an American agent of Nazi Germany.

He did what he could to redeem himself for those sins. He had always had Jewish friends, and they remained true to him. He promoted Jewish architects, built a synagogue without fee, and designed a nuclear reactor for the Israeli state. Did he expiate himself? The very question suggests Johnsons greatest gift, his unmatched capacity to occupy two poles at once.