Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street

Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

www.blackincbooks.com

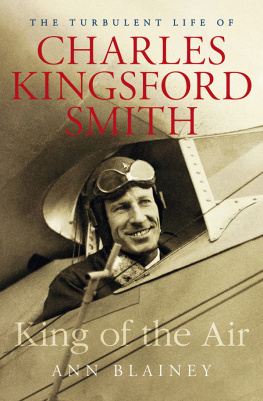

Copyright Ann Blainey 2018

Ann Blainey asserts her right to be known as the author of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of material in this book. However, where an omission has occurred, the publisher will gladly include acknowledgement in any future edition.

9781760641078 (hardback)

9781743820711 (ebook)

Cover design by Tristan Main

Text design and typesetting by Marilyn de Castro

Index by Kerry Anderson

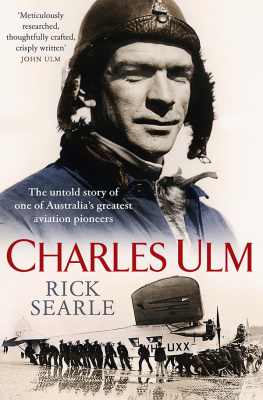

Cover photograph by Aviation History Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

Back cover photograph courtesy of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences

(photographer unknown; gift of Austin Byrne, 1965)

To my father,

Commander Frances William Heriot

PREFACE

I have known about Charles Kingsford Smith since I was eleven years old. On my schoolroom wall there was a map of the Pacific with the pioneering route of his plane, the Southern Cross, painted in red. That year in my history class I also learned about Magellan and Columbus, but my enthusiasm centred on Smithy. He was an Australian, and about the same age as my male cousins, which gave me a sense of kinship. Moreover, my mother had made a short trip in the Southern Cross. And my father, a navigator with the Royal Australian Navy, had charted parts of the coastline over which Smithy had flown, and could explain what extraordinary flights his had been. I began to wonder what Smithy was really like.

Perhaps that is why my book tries to focus on the inner as well as the outer man. Having been world-famous for so long, his career highlights are widely known, but his hopes and doubts, his impetuosity and patience, his courage and fears, are less well understood. And yet his states of mind play crucial roles in his dazzling success and his final disaster.

My book also examines his relationship with fame, for Smithy was revered as the greatest aviator of his generation, and is today accounted one of the most famous Australians of all time. Fame is a tricky companion. How did Smithy cope with such a conspicuous friend and enemy? How did it shape his short life? In an earlier book of mine a biography of the celebrated soprano Dame Nellie Melba I tried as best I could to fathom her surrounding fame and its effects. While Smithy rejoiced in his fame, he could never manage to master it.

Half a dozen people have written accounts of his life, starting with Beau Sheil and Norman Ellison in 1937, less than two years after Smithy and his plane vanished near Myanmar. Ellison did not publish his biography for another twenty years and even then it was uncompleted but it is still a valuable source for biographers. His collection of letters and documents, many given to him by Smithys family, reside today in the Ellison Collection of the National Library of Australia, and also remain a precious resource for a biographer.

Since then several large biographies have appeared, such as those by Ian Mackersey and Peter FitzSimons, to both of whom I am indebted. For his widely read book, Mackersey secured interviews, in the 1990s, with Kingsford Smiths two wives and a number of his associates, none of whom is still living. Thanks to his foresight, much valuable information has been bequeathed to future biographers and historians, and I have gratefully drawn on it. To Mr FitzSimons I also owe a debt: his sparkling account of Smithys exploits has renewed public interest in the great aviators achievements.

Another debt is to Pedr Davis, the author of books on both Smithy and his fellow aviator Keith Anderson. Pedr has provided encouragement and practical help, reading my typescript and picking up errors. I sincerely thank him.

In my quest to find the man beneath the image, I have been much helped by the excellent reportage in the newspapers of the time. Smithy gave many interviews, and often spoke to reporters with a spontaneity and candour that is missing in his official writings. The Sydney Sun chronicled his career in useful detail, but it is in such outback West Australian newspapers as Carnarvons The Northern Times and The Pilbara Goldfield News that one comes across episodes and attitudes that have so far been little examined.

While out-of-the-way newspapers have been of considerable help, I could not have written this book without the assistance of librarians and archivists around Australia. I thank particularly those of the National Library of Australia, the National Archives of Australia, the Mitchell Library in the State Library of New South Wales, the State Archives of New South Wales and the John Oxley Library in the State Library of Queensland.

I am also deeply grateful for the help of friends. John Day checked my page proofs; John Drury loaned me books; Nicole Ritzdorf translated a difficult German text for me; Gaynor Sinopolis arranged for me to climb up to the cramped cockpit of the immortal Southern Cross, now housed proudly at Brisbane Airport; Lady (Marie) Fisher took me to Smithys birthplace in Brisbane.

Martin Price unearthed obscure facts for me in British archives, and Kathryn Lindsay unearthed others in Vancouver. In Sydney, Charles and Amelia Slack-Smith gave me details of Smithys parents house in Arabella Street; Dr Allan Beavis obtained a copy of Smithys classroom report at the Cathedral school; and Kitty Greenwood described her mothers romance with the young Kingsford Smith. Nor should I forget Smithys grandniece, Kristin King, and Smithys son, Charles Arthur Kingsford Smith, who lives on the west coast of the United States. They answered questions and gave encouragement. I thank them all.

Before writing about Smithys panic disorder, I gained from discussions in Melbourne with Ms Roslyn Glickfeld, a psychoanalyst, and Professor Nicolino Paoletti, a psychiatrist, both well known in their fields. Moreover, Nicolino took time from his busy schedule to read and correct crucial chapters in my typescript.

Lastly, I must thank my publisher, Chris Feik, and my husband, Geoffrey Blainey. My husband travelled with me to many of Smithys airfields and flight paths, including to outback Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, North America and Asia, including the steamy coastline of Myanmar, where Smithy met his end. I also thank my daughter, Anna, and my son-in-law, Tim Warner, whose knowledge of navigation has been most welcome. They have been obliged to live with Smithy for a long time, and their support has never flagged.

ANN BLAINEY

Melbourne, 2018

SUNNY FACED, SUNNY HEARTED, SUNNY TEMPERED

I t was dawn on the foggy morning of 9 June 1928, and people were swarming over the frosty paddocks of Eagle Farm, which served as Brisbanes aerodrome. Some had been there since well before midnight; others, with coats and scarves over their evening clothes, had arrived later, coming from dances and parties. As the sun rose, the long road skirting the river was dotted with walkers, while trams brought thousands more to the nearest stop. They walked the rest of the way in the cold. And certainly it was cold but not cold enough, one woman said, to stop Australian hearts beating warmer than ever.

Next page