Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Kamkwamba, William, date, author.

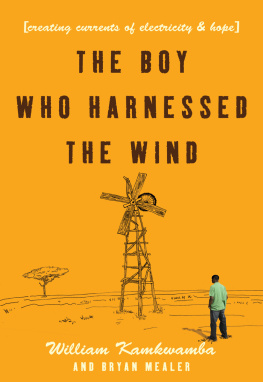

The boy who harnessed the wind / William Kamkwamba and Bryan Mealer. Young readers edition.

1. Kamkwamba, William, dateJuvenile literature. 2. Mechanical engineersMalawi

BiographyJuvenile literature. 3. InventorsMalawiBiographyJuvenile literature.

4. WindmillsMalawiJuvenile literature. 5. Electric power productionMalawiJuvenile literature.

6. IrrigationMalawiJuvenile literature. I. Mealer, Bryan. II. Title.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

PROLOGUE

The machine was ready. After so many months of preparation, the work was finally complete: The motor and blades were bolted and secured, the chain was taut and heavy with grease, and the tower stood steady on its legs. The muscles in my back and arms had grown as hard as green fruit from all the pulling and lifting. And although Id barely slept the night before, Id never felt so awake. My invention was complete. It appeared exactly as Id seen it in my dreams.

News of my work had spread far and wide, and now people began to arrive. The traders in the market had watched it rise from a distance and theyd closed up their shops, while the truck drivers left their vehicles on the road. Theyd crossed the valley toward my home, and now they gathered under the machine, looking up in wonder. I recognized their faces. These same men had teased me from the beginning, and still they whispered, even laughed.

Let them, I thought. It was time.

I pulled myself onto the towers first rung and began to climb. The soft wood groaned under my weight as I reached the top, where I stood level with my creation. Its steel bones were welded and bent, and its plastic arms were blackened from fire.

I admired its other pieces: the bottle-cap washers, rusted tractor parts, and the old bicycle frame. Each one told its own story of discovery. Each piece had been lost and then found in a time of fear and hunger and pain. Together now, we were all being reborn.

In one hand I clutched a small reed that held a tiny lightbulb. I now connected it to a pair of wires that dangled from the machine, then prepared for the final step. Down below, the crowd cackled like hens.

Quiet, everyone, someone said. Lets see how crazy this boy really is.

Just then a strong gust of wind whistled through the rungs and pushed me into the tower. Reaching over, I unlocked the machines spinning wheel and watched it begin to turn. Slowly at first, then faster and faster, until the whole tower rocked back and forth. My knees turned to jelly, but I held on.

I pleaded in silence: Dont let me down.

Then I gripped the reed and wires and waited for the miracle of electricity. Finally, it came, a tiny flicker in my palm, and then a magnificent glow. The crowd gasped, and the children pushed for a better look.

Its true! someone said.

Yes, said another. The boy has done it. He has made electric wind!

CHAPTER ONE

WHEN MAGIC RULED THE WORLD

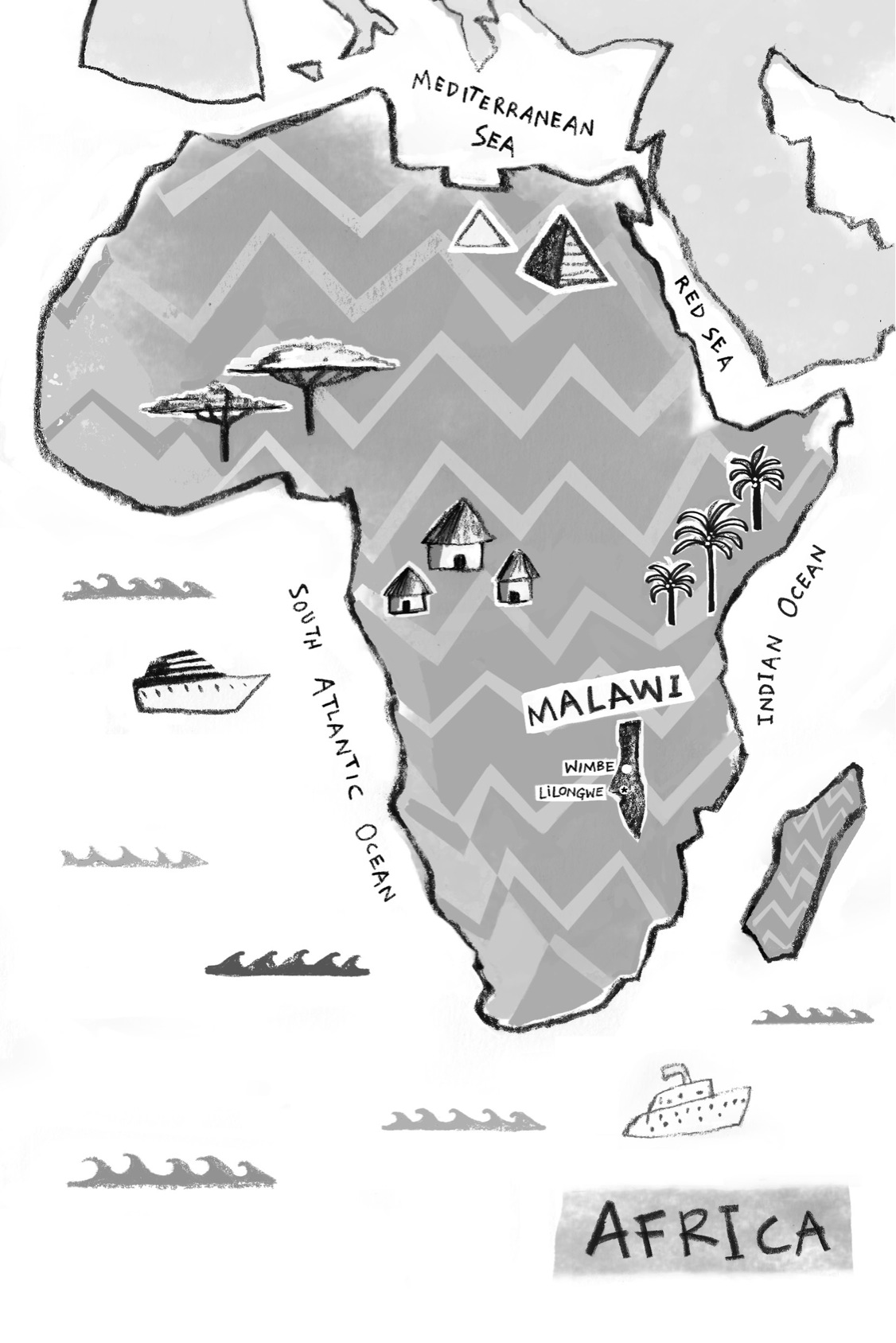

My name is William Kamkwamba, and to understand the story Im about to tell, you must first understand the country that raised me. Malawi is a tiny nation in southeastern Africa. On a map, it appears like a flatworm burrowing its way through Zambia, Mozambique, and Tanzania, looking for a little room. Malawi is often called The Warm Heart of Africa, which says nothing about its location, but everything about the people who call it home. The Kamkwambas hail from the center of the country, from a tiny village called Masitala, located on the outskirts of the town of Wimbe.

You might be wondering what an African village looks like. Well, ours consists of about ten houses, each one made of mud bricks and painted white. For most of my life, our roofs were made from long grasses that we picked near the swamps, or dambos in our Chichewa language. The grasses kept us cool in the hot months, but during the cold nights of winter, the frost crept into our bones and we slept under an extra pile of blankets.

Every house in Masitala belongs to my large extended family of aunts and uncles and cousins. In our house, there was me, my mother and father, and my six sisters, along with some goats and guinea fowl, and a few chickens.

When people hear Im the only boy among six girls, they often say, Eh,bambowhich is like saying Hey, manso sorry for you! And its true. The downside to having only sisters is that I often got bullied in school since I had no older brothers to protect me. And my sisters were always messing with my thingsespecially my tools and inventionsgiving me no privacy.

Whenever I asked my parents, Why do we have so many girls in the first place? I always got the same answer: Because the baby store was all out of boys. But as youll see in this story, my sisters are actually pretty great. And when you live on a farm, you need all of the help you can get.

My family grew maize, which is another word for white corn. In our language, we lovingly referred to it as chimanga. And growing chimanga required all hands. Every planting season, my sisters and I would wake up before dawn to hoe the weeds, dig our careful rows, then push the seeds gently into the soft soil. When it came time to harvest, we were busy again.

Most families in Malawi are farmers. We live our entire lives out in the countryside, far away from cities, where we can tend our fields and raise our animals. Where we live, there are no computers or video games, very few televisions, and for most of my life, we didnt have electricityjust oil lamps that spewed smoke and coated our lungs with soot.

Farmers here have always been poor, and not many can afford an education. Seeing a doctor is also difficult, since most of us dont own cars. From the time were born, were given a life with very few options. Because of this poverty and lack of knowledge, Malawians found help wherever we could.