Contents

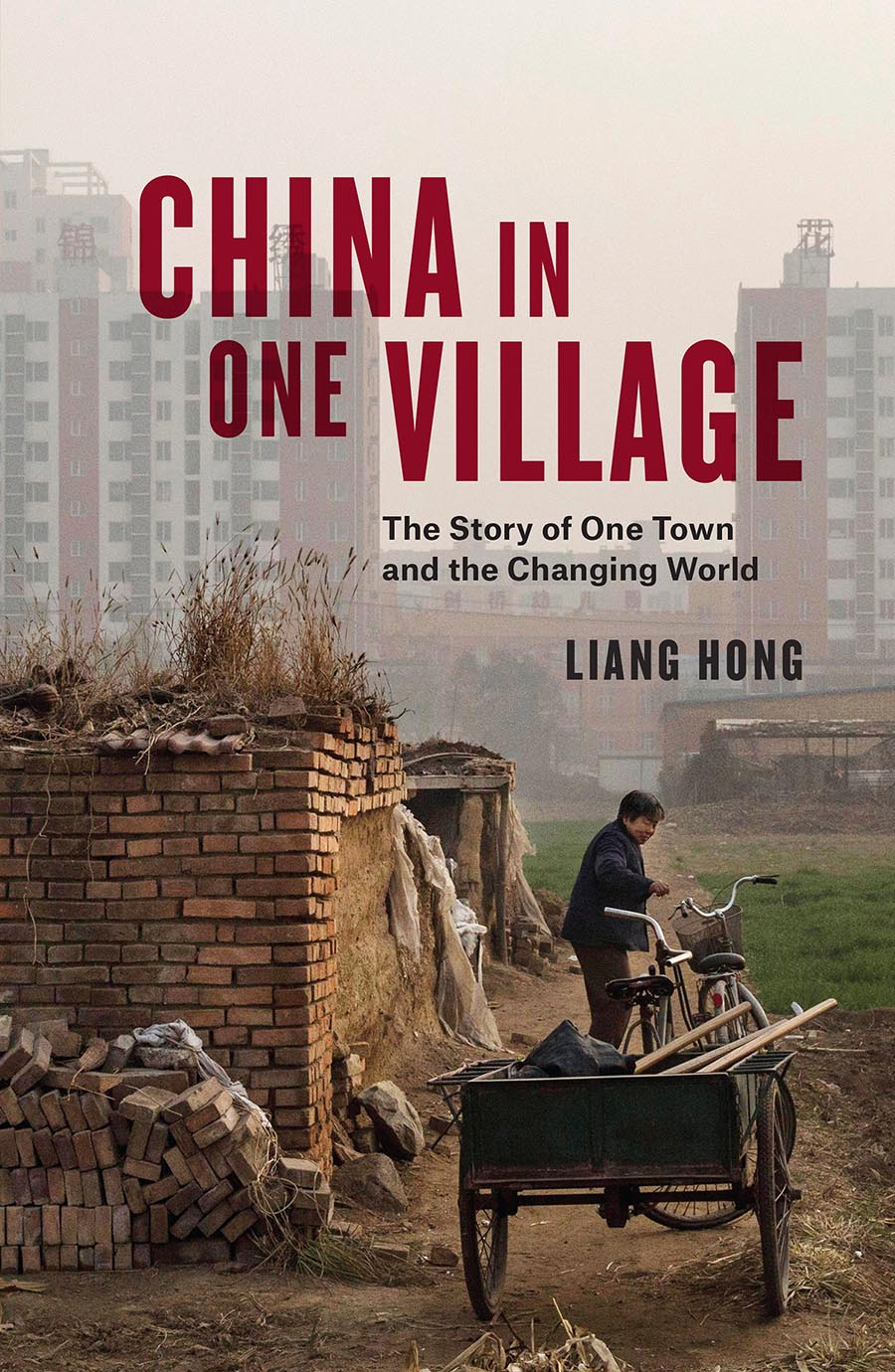

China in One Village

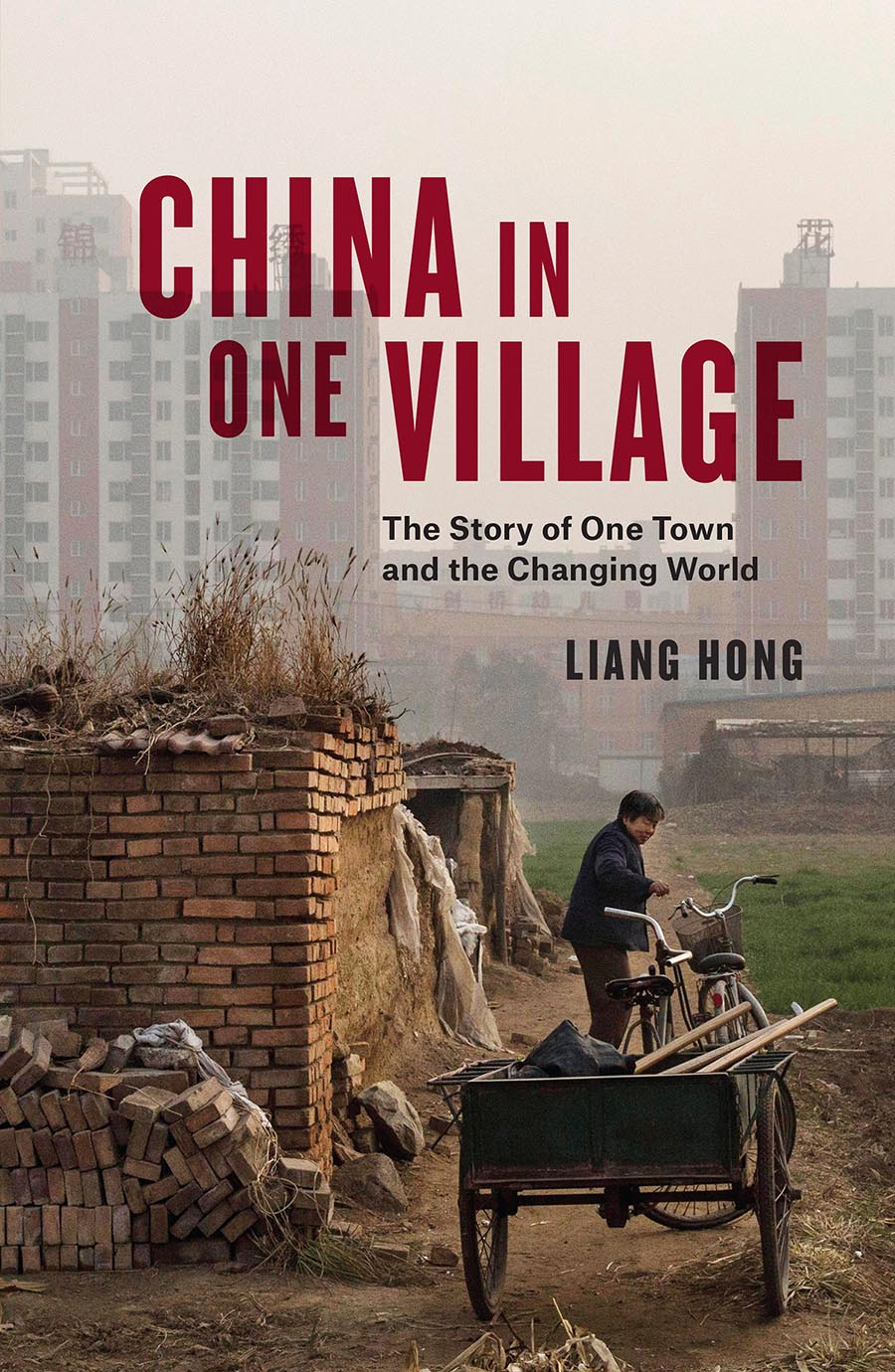

China in One Village

The Story of One Town

and the Changing World

Liang Hong

Translated by Emily Goedde

First published in English by Verso 2021

Translation Emily Goedde 2021

Translation of the Preface and Afterword Natascha Bruce 2021

Originally published as  2010

2010

Published with support from the China

Translation and Publishing House

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author and translator have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-177-5

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-556-8 (EXPORT)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-178-2 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-179-9 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021930158

Typeset in Sabon by Biblichor Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

A decade ago, I took a train trip from my home in Beijing to a far-flung corner of China, a village in rural Henan Province. Originally, I merely intended to write a travel diary of a trip to Liang Village, the community where I was born and grew up. But by the time the book was published, followed a few years later by a second book, it contained things that were called sociological field investigations and anthropological oral histories. The books sold hundreds of thousands of copies and kickstarted a trend in contemporary Chinese literary non-fiction.

I had absolutely no idea that it would provoke such a huge reaction, and Ive given a lot of thought to the reasons for this. Inadvertently, the book seems to have touched on a very fundamental concern, which has nevertheless been consistently overlooked: In rapidly developing, increasingly urbanized China, what is happening in the countryside? After all, this countryside is where the majority of Chinese people come from. Concern for its uncertain fate lurks within us all. Society is developing too fastwe dont go home for a year, and when we do familiar roads and trees have vanished; two or three years, and the river behind the village has gone. Our villages are increasingly deserted, many left almost in ruins. This has led to a sense of psychological homelessness and a deep, steadily building sorrow. I wrote China in One Village on behalf of everyone affected by this. On behalf of us all, I raise the questions: What on earth is going on in the Chinese countryside? What on earth is happening to my home?

Another reason for the reaction is surely the style in which I wrote the book: as though on the scene. From the start, I wanted to convey a sense of immediacyfor a reader to come with me to the fields around Liang Village, then to come with me inside villager such-and-suchs home, sit down, look into their eyes, make conversation, listen to their stories. I wanted each reader to feel as if they were back in their own village, meeting the villagers there, seeing their own rivers and little streams. Theres an intrinsic universality to that experience. Later, while I was traveling for research, whenever I spoke about the book people always wanted to talk to me about their own villages and what had happened to them; never about Liang Village. This is important to keep in mind.

Even readers born in cities have been deeply moved by China in One Village. Some have written me letters about it or posted essays online. Its made me think that the so-called native soil experience of our agricultural civilization still lingers deep in the soul of every Chinese person. Its a kind of collective subconscious, at the root of our experience of the world.

But no matter how readers understand this book, how scholars and officials choose to interpret it, or how many academic disciplines happen to be touched upon inside it, I will always insist that it is literature, first and foremost. Because, ultimately, it is about people. It describes the complex fabric of contemporary Chinese society and tells the story of our lives. It relies on emotion, rather than using the language of logic and reason to produce an account of social norms and community attributes.

And so, while reading this book, I hope you will keep an open heart. Regardless of the genre, regardless of where the story is from, you and I are in this togetherwere on a train, setting off on a journey to Liang Village. In a remote corner of this vast land we call China, a village, a community, and a river await. They are waiting for you to walk on in.

_______________

In 2009, Peoples Literature [Renmin Wenxue] magazine started a column called Non-Fiction (Feixugou). In 2010, it ran pieces including Liang Village by Liang Hong, China: In the Absence of a Remedy by Murong Xuecun, and Southern Dictionary by Xiao Xiangfeng, sparking widespread conversations and debates. As a result, literary non-fiction articles began to feature in large numbers on literary, news media, and social-media platforms, establishing the genre as both a literary phenomenon and a lasting trend.

Published in China as Zhongguo zai Liangzhuang by Jiangsu Art Publishing House, October 2010 and Chu Liangzhuang Ji by Flower City Publishing House, April 2013. As is common practice in Chinese literary non-fiction, Liang Village is a made-up name, and characters and relationships described in the book have been altered to protect privacy.

Last night I hardly slept. The jolting train kept my son, three years and two months old, from sleeping soundly. The slightest discomfort had him swinging his arms, tossing and turning. To keep him from falling out of the bunk, I lay at his feet and put my legs around him, but he, in his dreams, kept pushing them away. In the end I sat up, turned on the little lamp at the head of the bed, and read the book I had brought with me: The Outermost House: A Year of Life on the Great Beach of Cape Cod by the American naturalist Henry Beston. Beston wrote this collection of essays after spending a season on an isolated stretch of the Cape Cod coast. There he was in direct contact with the majestic ocean, all kinds of seabirds, unpredictable weather, and the omnipresent perils of the sea. You can sense the richness, precision, and deep love with which his gaze took everything in. The natural world and humankind became one:

Whatever attitude to human existence you fashion for yourself, know that it is valid only if it be the shadow of an attitude to Nature. A human life, so often likened to a spectacle upon a stage, is more justly a ritual. The ancient values of dignity, beauty, and poetry which sustain it are of Natures inspiration; they are born of the mystery and beauty of the world. Do no dishonor to the earth lest you dishonor the spirit of man. Hold your hands out over the earth as over a flame. To all who love her, who open to her the doors of their veins, she gives of her strength, sustaining them with her own measureless tremor of dark life.

Lifes meaning and the true nature of human existence only take form when joined with the natural world. You are insignificant. You are also immense. And you become eternal, for humankind is only one part of the whole.

2010

2010