for Leslie

CONTENTS

Book I

The Wall

Book II

The Village

Book III

The Factory

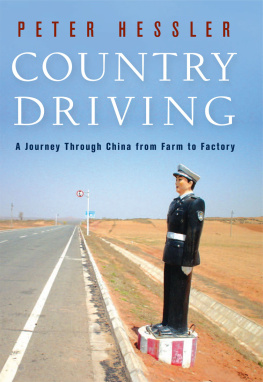

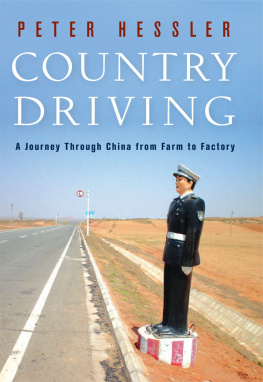

T HERE ARE STILL EMPTY ROADS IN C HINA, ESPECIALLY on the western steppes, where the highways to the Himalayas carry little traffic other than dust and wind. Even the boomtowns of the coast have their share of vacant streets. They lead to half-built factory districts and planned apartment complexes; they wind through terraced fields that are destined to become the suburbs of tomorrow. They connect villages whose residents traveled by foot less than a generation ago. It was the thought of all that fleeting open spacethe new roads to old places, the landscapes on the verge of changethat finally inspired me to get a Chinese drivers license.

By the summer of 2001, when I applied to the Beijing Public Safety Traffic Bureau, I had lived in China for five years. During that time I had traveled passively by bus and plane, boat and train; I dozed across provinces and slept through towns. But sitting behind the wheel woke me up. That was happening everywhere: in Beijing alone, almost a thousand new drivers registered on average each day, the pioneers of a nationwide auto boom. Most of them came from the growing middle class, for whom a car represented mobility, prosperity, modernity. For me, it meant adventure. The questions of the written drivers exam suggested a world where nothing could be taken for granted:

223. If you come to a road that has been flooded, you should

a) accelerate, so the motor doesnt flood.

b) stop, examine the water to make sure its shallow, and drive across slowly.

c) find a pedestrian and make him cross ahead of you.

282. When approaching a railroad crossing, you should

a) accelerate and cross.

b) accelerate only if you see a train approaching.

c) slow down and make sure its safe before crossing.

Chinese applicants for a license were required to have a medical checkup, take the written exam, enroll in a technical course, and then complete a two-day driving test; but the process had been pared down for people who already held overseas certification. I took the foreigners test on a gray, muggy morning, the sky draped low over the city like a shroud of wet silk. The examiner was in his forties, and he wore white cotton driving gloves, the fingers stained by Red Pagoda Mountain cigarettes. He lit one up as soon as I entered the automobile. It was a Volkswagen Santana, the nations most popular passenger vehicle. When I touched the steering wheel my hands felt slick with sweat.

Start the car, the examiner said, and I turned the key. Drive forward.

A block of streets had been cordoned off expressly for the purpose of testing new drivers. It felt like a neighborhood waiting for life to begin: there werent any other cars, or bicycles, or people; not a single shop or makeshift stand lined the sidewalk. No tricycles loaded down with goods, no flatbed carts puttering behind two-stroke engines, no cabs darting like fish for a fare. Nobody was turning without signaling; nobody was stepping off a curb without looking. I had never seen such a peaceful street in Beijing, and in the years that followed I sometimes wished I had had time to savor it. But after I had gone about fifty yards the examiner spoke again.

Pull over, he said. You can turn off the car.

The examiner filled out forms, his pen moving efficiently. He had barely burned through a quarter of a Red Pagoda Mountain. One of the last things he said to me was, Youre a very good driver.

The license was registered under my Chinese name, Ho Wei. It was valid for six years, and to protect against counterfeiters, the document featured a hologram of a man standing atop an ancient horse-drawn carriage. The figure was dressed in flowing robes, like portraits of the Daoist philosopher Lao Tzu, with an upraised arm pointing into the distance. Later that year I set out to drive across China.

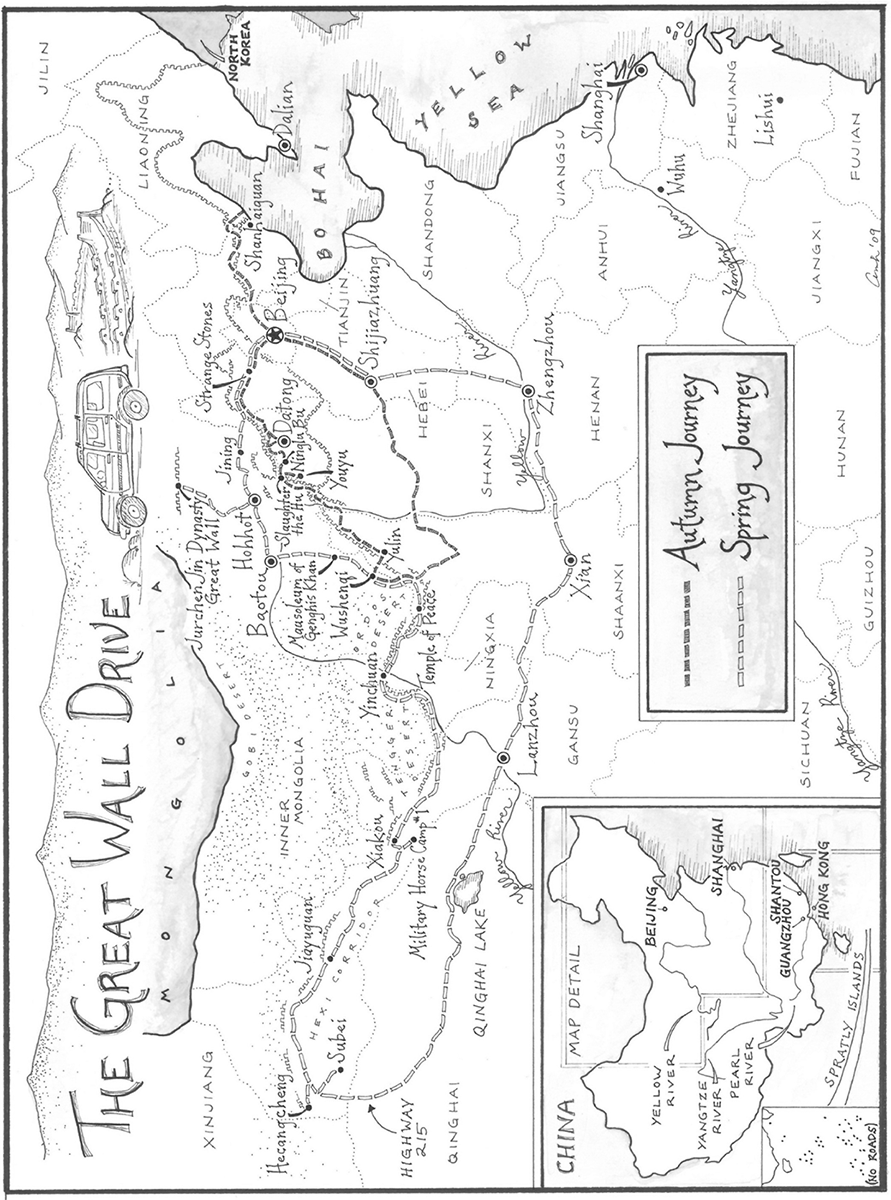

W HEN I BEGAN PLANNING my trip, a Beijing driver recommended The Chinese Automobile Drivers Book of Maps. A company called Sinomaps published the book, which divided the nation into 158 separate diagrams. There was even a road map of Taiwan, which has to be included in any mainland atlas for political reasons, despite the fact that nobody using Sinomaps will be driving to Taipei. Its even less likely that a Chinese motorist will find himself on the Spratly Islands, in the middle of the South China Sea, territory currently disputed by five different nations. The Spratlys have no civilian inhabitants but the Chinese swear by their claim, so the Automobile Drivers Book of Maps included a page for the island chain. That was the only map without any roads.

Studying the book made me want to go west. The charts of the east and south looked busycountless cities, endless tangled roads. Since the beginning of Reform and Opening, the period of free-market economic changes initiated by Deng Xiaoping in 1978, development has been most intense in the coastal regions. The whole country is moving in that direction: at the time of my journey, approximately ninety million people had already left the farms, mostly bound for the southeast, and the routines of rural life were steadily giving way to the rush of factory towns. But the north and the west were still home to vast stretches of agricultural land, and the maps of those regions had a sense of space that appealed to me. Roads were fewer, and so were towns. Sometimes half a page was filled by nothing but sprinkled dots, which represented desert. And the western maps covered more spacein northern Tibet, a single page represented about one-fifteenth of Chinas landmass. In the book it looked the same size as Taiwan. None of the Sinomaps had a marked scale. Occasionally, tiny numbers identified the distance in kilometers between towns, but otherwise it was anybodys guess.

Most roads were also unlabeled. Expressways appeared as thick purple arteries, while national highways were red veins coursing between the bigger cities. Provincial roads were a thinner red, and county and local roads were smaller yettiny capillaries squiggling through remote areas. I liked the idea of following these little red roads, but not a single one had a name. The page for the Beijing region included seven expressways, ten highways, and over one hundred minor roadsbut only the highways were numbered. I asked the Beijing driver about the capillaries.

They dont name roads like that, he said.

So how do you know where you are?

Sometimes there are signs that give the name of the next town, he said. If there isnt a sign, then you can stop and ask somebody how to get to wherever you want to go.

The drivers exam touched on this too:

352. If another motorist stops you to ask directions, you should

a) not tell him.

b) reply patiently and accurately.

c) tell him the wrong way.

Thousands of nameless roads webbed the Sinomaps, and it was impossible to find one clear route across the west. But another symbol was less confusing:

Next page