THIS IS A WORK OF NONFICTION, AND I HAVE USED REAL NAMES WITH one exception: Polat. The pseudonym is used at his request, because of political sensitivities in the Peoples Republic of China.

This book was researched from 1999 to 2004, a period whose events are still resonating. I expect that in the future we will learn more about these occurrences, and my depiction is not intended to be comprehensive or definitive. My goal has been to follow certain individuals across this period, recording how their lives were shaped by a changing world.

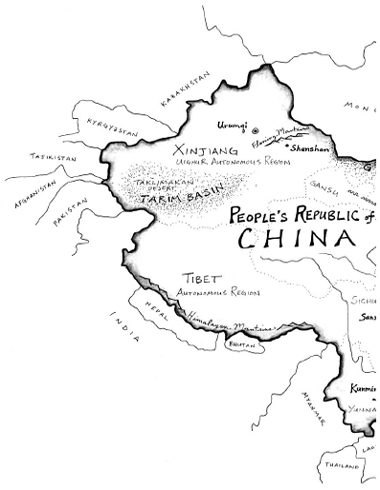

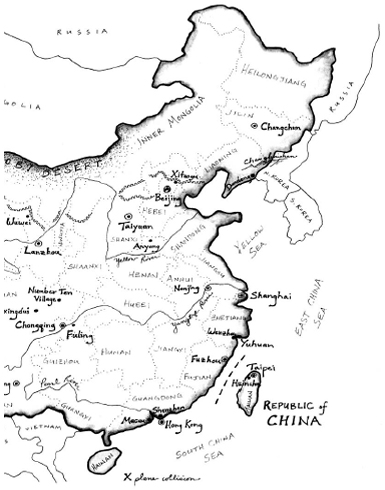

These people led me to many placessome in China, some in the United States, and others, such as Xinjiang and Taiwan, that are in dispute. Boundaries and definitions often seemed fluid, and so did time itself. The main chapters of this book are arranged chronologically, but the short sections labeled artifacts are not. They reflect a deeper sense of timethe ways in which people make sense of history after it has receded farther into the past.

Polat means steel in the Uighur language, and he chose that name because of the qualities that he believed are necessary for anybody far from home.

FROM BEIJING TO ANYANGFROM THE MODERN CAPITAL TO THE CITY known as a cradle of ancient Chinese civilizationit takes six hours by train. Sitting by the window, there are moments when a numbness sets in, and the scenery seems as patterned as wallpaper: a peasant, a field, a road, a village; a peasant, a field, a road, a village. This sense of repetition is not new. In 1981, David N. Keightley, an American professor of history, took the train to Anyang. Afterward, he wrote in a letter to his family: The land is generally flat, monotonous, one village much like another. Where are the gentry estates, the mansions, the great houses of England and France? What was it about this society that failed to produce such monuments to civilized aristocratic living?

Move back in time, and its the same: a peasant, a field, a road, a village. In the 1930s, a foreign resident named Richard Dobson wrote: There is no history in Honan. Today, that seems an unlikely remark, because this region is known as the archives and the grave of the Shang dynasty. The Shang produced the earliest known writing in East Asia, inscribed into bones and shellsthe oracle bones, as they are called in the West. If one defines history as written records, this part of Henan is where it all began for China.

But visitors have often wondered about something other than origins. Move back in time once more, to the 1880s, when an American named James Harrison Wilson wrote: They have stood absolutely still in knowledge since the middle ages. He explained, The essence of their history can be told in a few short chapters. It has to do with trajectory, progressexpectations of the West. In the traditional view of the Chinese past, there is no equivalent of the fall of Rome, no Renaissance, no Enlightenment. Instead, emperor succeeds emperor, and dynasty follows dynasty. History as wallpaper. In A Truthful Impression of the Country, an analysis of Western travel writing about China, Nicholas R. Clifford describes this nineteenth-century foreign perspective: China had a far longer past than the Westno one would think of denying thatbut the past and history are not the same thing. Here in Chinas past there was no narrative but only stories.

IN ANYANG, AT an archaeological site called Huanbei, a small group of men work in a field, mapping an underground city. The city dates to the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries B . C ., when the Shang culture was probably approaching its peak. Nowadays, the Shang ruins lie far beneath the soil, usually at a depth of five to eight feet. Peasants have planted crops for centuries without realizing that an entire city waited beneath them.

The layers of earth accumulated over time. This site is bordered by the Huan River, and periodic floods have deposited alluvial soil onto the field. There is also loess: thin, dry particles that originated from the Gobi and other deserts of the northwest. Loess is easily windborne, and over the centuries, layers of it have been blown south and then redeposited in places like Anyang. In northern China, the yellow earth can be as deep as six hundred feet.

Elsewhere in the world, archaeologists search for ridges and mounds, visible signs of buried structures. But here the naked eye isnt adequate; a two-dimensional view of Anyang reveals only flatness. The men in the field work under the direction of a young archaeologist named Jing Zhichun, who explains the challenges of research in a place like this.

You have to look at the landscape in a dynamic way, he says. You have to see the landscape evolving. It might be completely different from what it was three thousand years ago. Were looking at human society in three dimensions; its not just the surface that matters. We had to add another dimension: the time dimension. You can look all around here and see nothing, but in fact this was the first city in the area. If you dont add time, youll find nothing.

The workers are local peasants, and they dig with Luoyang spadesthe characteristic tool of Chinese archaeology. In Luoyang, one of Chinas many former capital cities, generations of grave robbers practiced their craft to the point of technical innovation: a tubular blade, cut in half like a scoop and then attached to a long pole. If you pound the blade straight into the earth and twist it slightly, you extract a core of soil about half a foot long and less than two inches in diameter. Do it again and againdozens of timesand the hole becomes a tiny shaft that penetrates six or more feet, bringing up deeper cores. When the shaft is deep enough, the dirt samples might contain bits of pottery or bone or bronze, or perhaps the hard tamped earth that was traditionally used to construct buildings.

Thieves developed the Luoyang spade, but during the first half of the twentieth century, Chinese archaeologists adopted the tool for their purposes. An experienced archaeologist can take a core from the deep earth, examine its contents, and determine whether he stands above an ancient buried wall, or a tomb, or a rubbish pit. The dirt plugs reflect the meaning of what lies below; they are like words that can be recognized at a glance.

For years, Jing and the others have been reading the earth in this part of Anyang. They began with a systematic survey, digging holes across the fields and checking for signs of buried structures. One series of random corings turned up an object: tamped earth, twenty feet wide, lying six feet beneath the surface. As they surveyed the underground structure, they realized that it ran as straight as an arrow. They followed it across the soybean fields, accumulating tiny holes and piles of cores in their wake. Three hundred yards, a thousand yardsmore holes, more cores. When the object suddenly stopped, they discovered a ninety-degree bend: a corner. At that point they realized that it must have been a settlement wall, and since then they have continued tracing the boundary and other interior structures. They are mapping a city that no living person has ever seen.