ALSO BY PETER HESSLER

Strange Stones

Country Driving

Oracle Bones

River Town

PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2019 by Peter Hessler

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Adieu, my old home by Leon Bassan, translated by Albert Bivas. Reprinted by permission of Albert Bivas.

Excerpts from The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant translated by Vincent A. Tobin, and The Hymn to the Aten translated by William Kelly Simpson, both published in The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry, edited by William Kelly Simpson (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2003).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hessler, Peter, 1969 author.

Title: The buried : an archaeology of the Egyptian revolution / Peter Hessler.

Description: New York : Penguin Press, 2019 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018050659 (print) | LCCN 2019015926 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525559573 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525559566 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Excavations (Archaeology)Egypt. | Hessler, Peter, 1969TravelEgypt. | EgyptDescription and travel. | Cairo (Egypt)Description and travel. | EgyptHistoryProtests, 20112013.

Classification: LCC DT60 (ebook) | LCC DT60 .H56 2019 (print) | DDC 962.05/6dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018050659

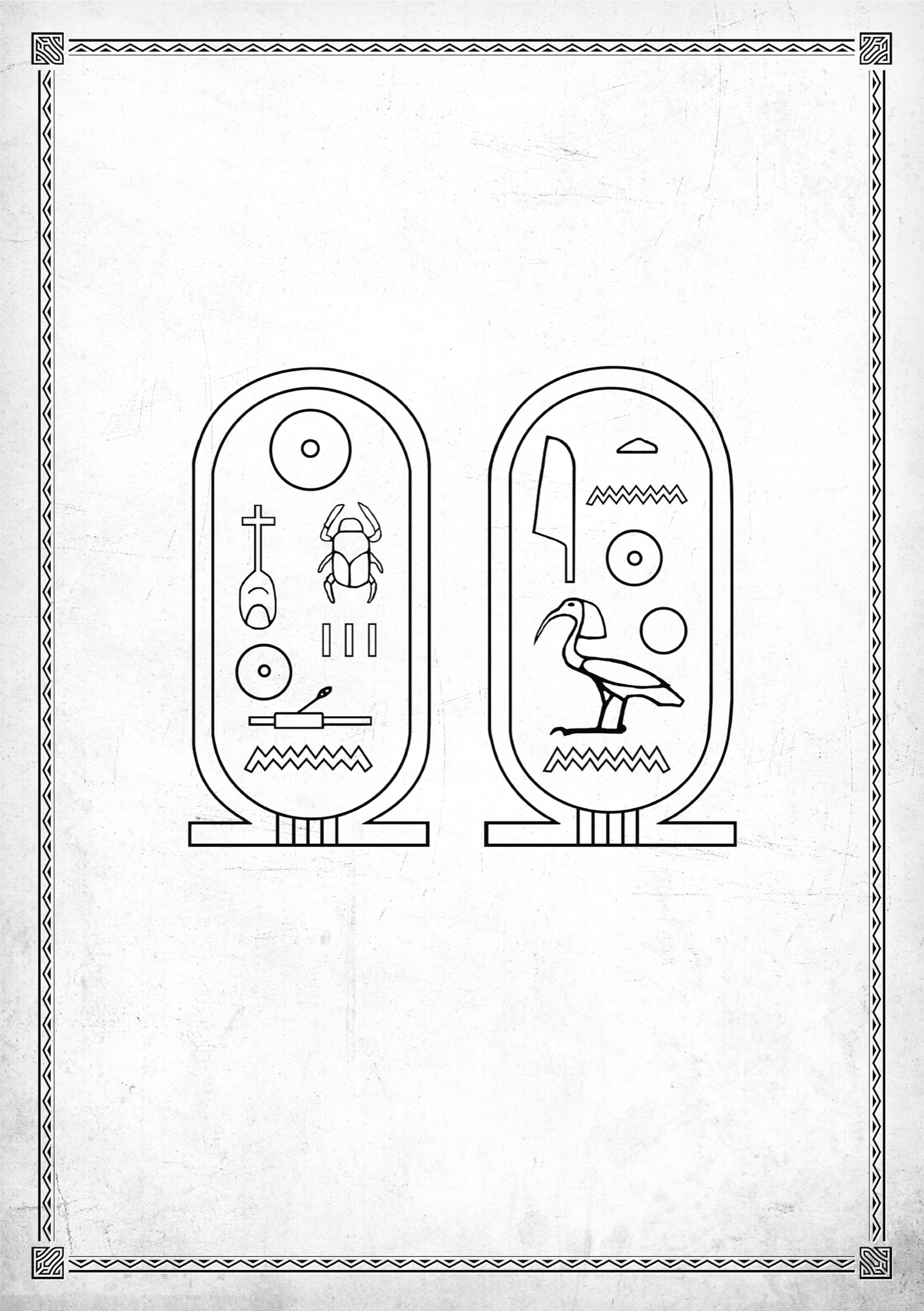

Page ornamentation by Daniel Lagin

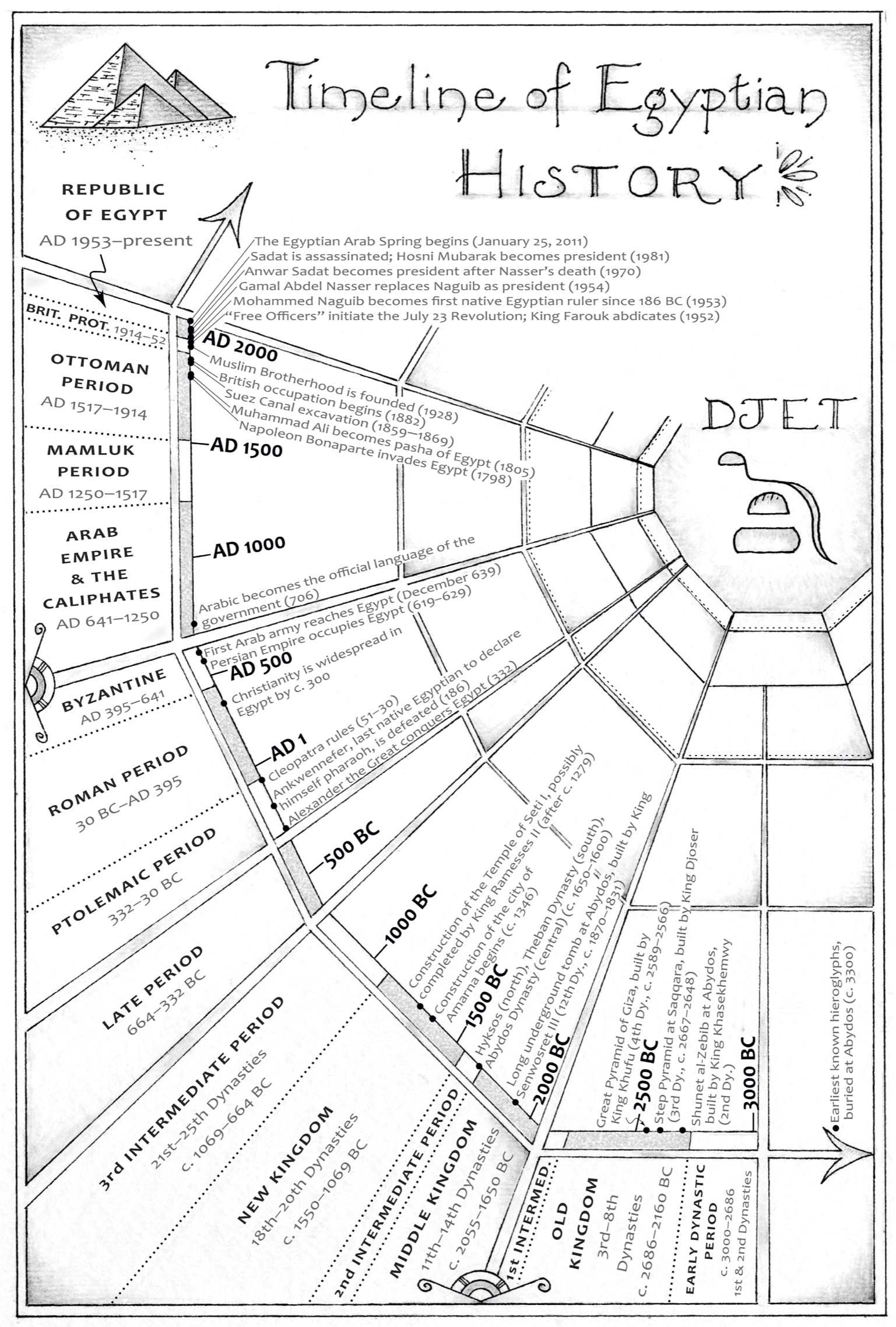

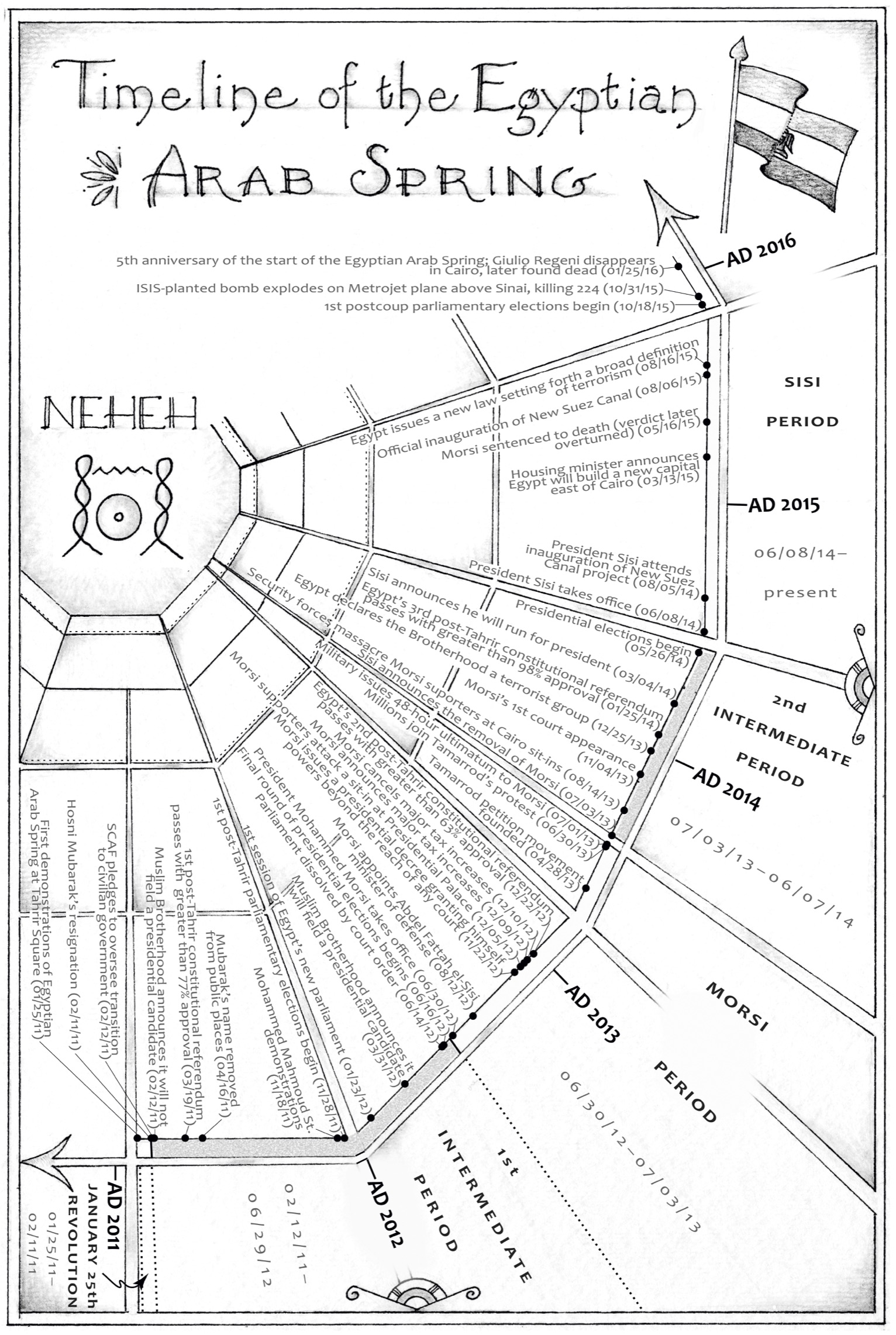

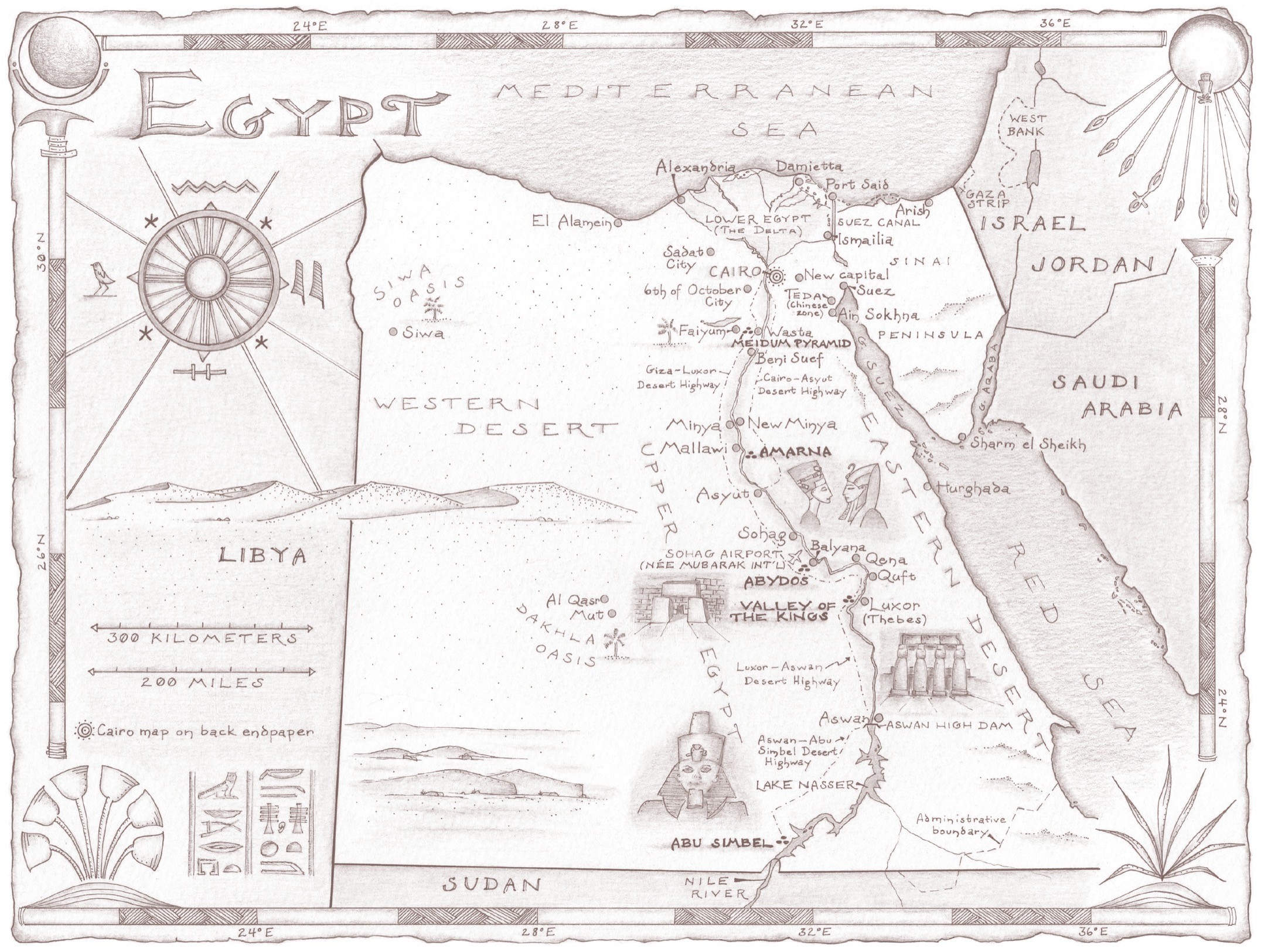

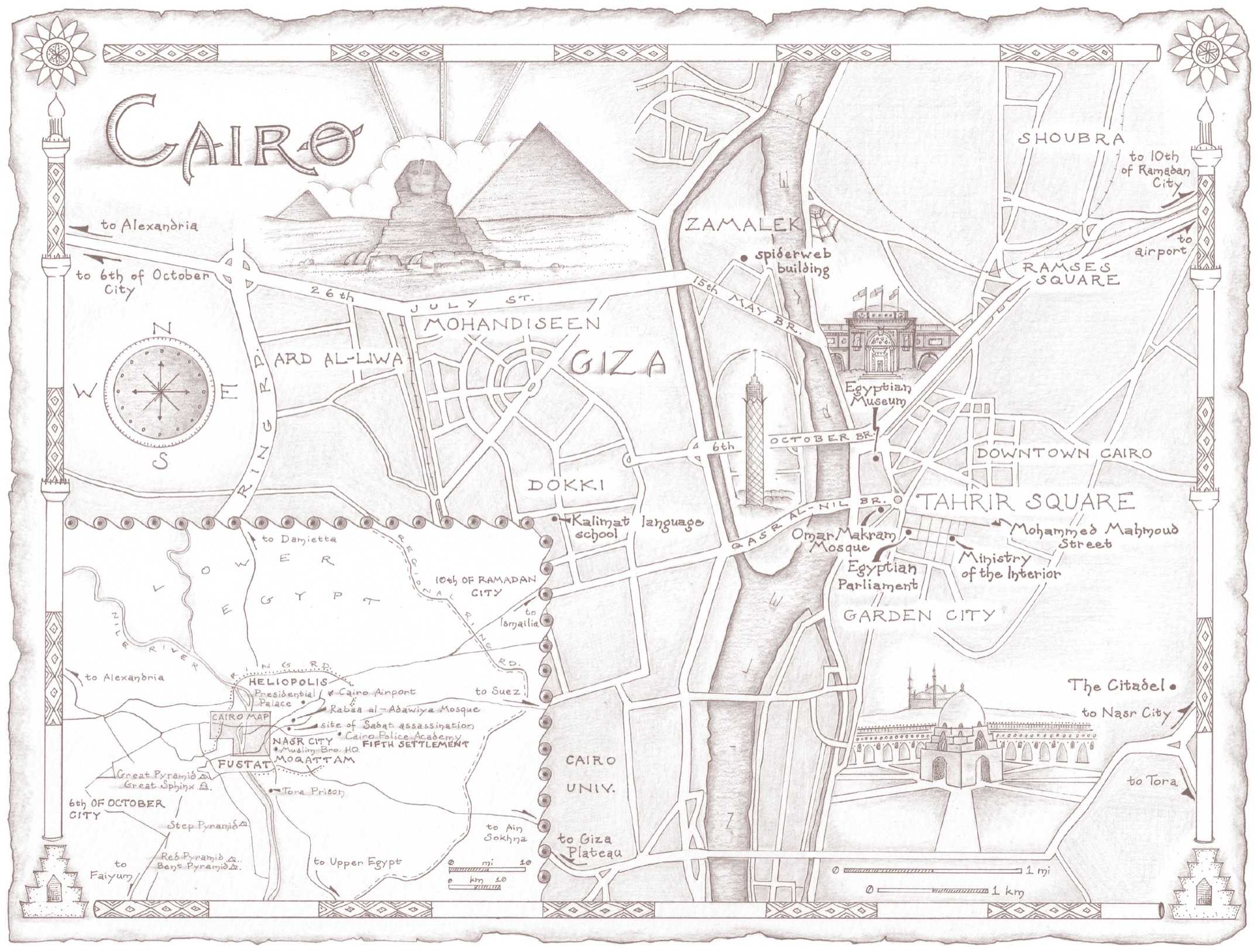

Endpaper maps and timelines by Angela Hessler

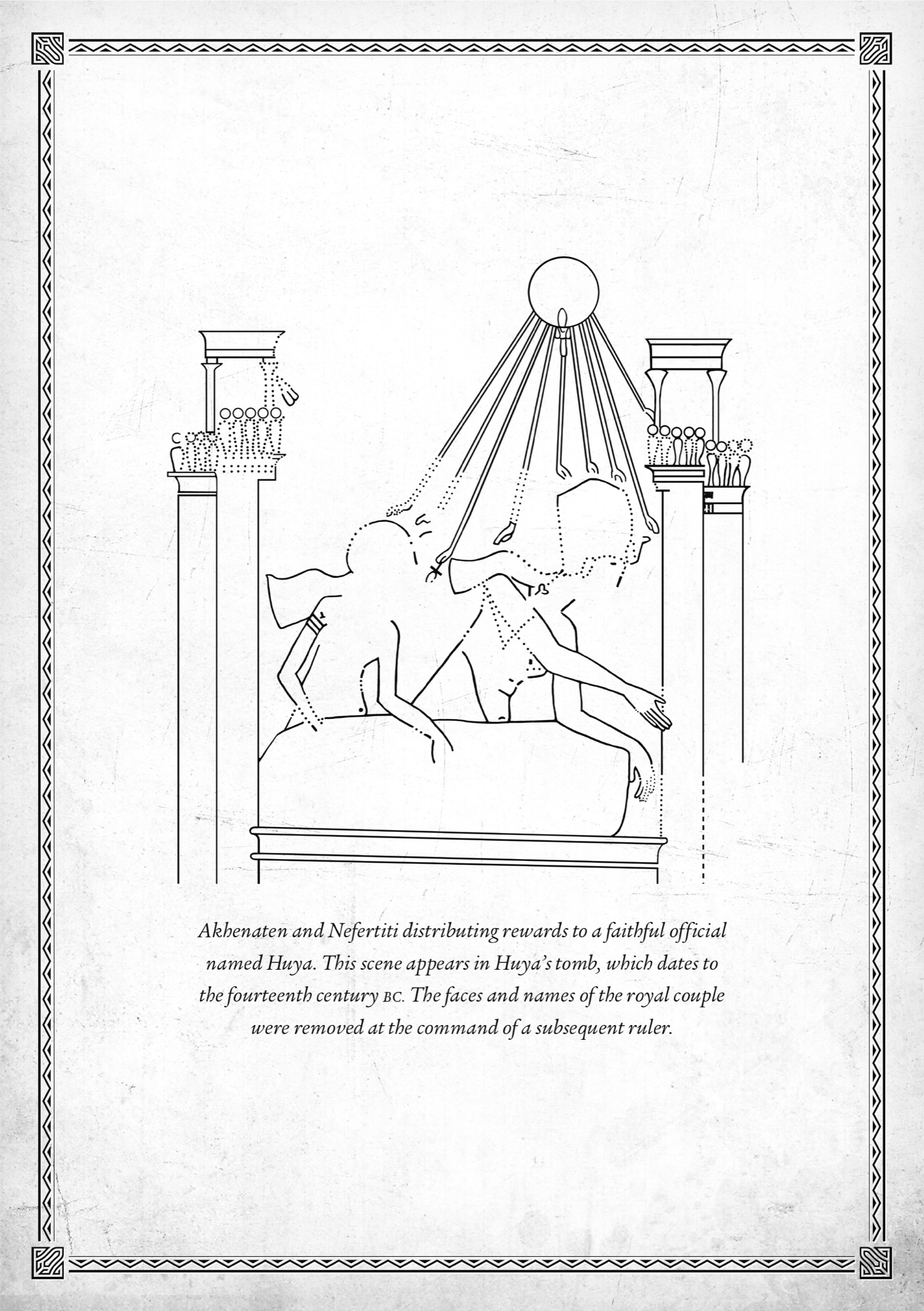

Illustrations by Meighan Cavanaugh

Version_2

For Doug Hunt

CONTENTS

Worship the king within your bodies,

Be well disposed towards His Majesty in your minds.

Cast dread of him daily,

Create jubilation for him every instant.

...................................

He sees what is in hearts;

His eyes, they search out every body.

The Loyalist Instruction, nineteenth century BC

CHAPTER 1

On January 25, 2011, on the first day of the Egyptian Arab Spring, nothing happened in Abydos. There were no demonstrations, no crowds, and no problems for the police. By that point in the winter excavation season, only one unusual incident had occurred. Earlier that month, a team of archaeologists from Brown University had uncovered a hole that contained two small bronze statues of Osiris, a small stone statue of the god Horus in child form, and exactly three hundred bronze coins.

The archaeologists had been excavating a series of tombs that had been looted thoroughly during antiquity, and they had neither expected nor hoped to find such relics. For Laurel Bestock, who was directing the dig, the immediate reaction was mixed. Along with the thrill of discovery, she felt a wave of nervousness, because now the team had to deal with more intense issues of security and bureaucracy. The local police contacted their superiors, and an official from the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities arrived. There was a great deal of paperwork to be filled out. Over a period of days, Bestock and the others worked long hours, and they painstakingly cleaned, measured, and photographed each of the coins and statues. Then everything was transported to Sohag, the capital of the region. The artifacts were locked in a wooden box that was placed in the back of a pickup truck and escorted by half a dozen policemen armed with rifles.

The objects themselves werent especially valuable. None of the statues was taller than ten inches, which made the departing processionthe truck, the police, the gunsslightly comical. The coins dated to the mid-Ptolemaic period, between the third and second centuries BC , which is late by the standards of Egyptology. For the archaeologists, the true value of the discovery was its context, because the relics appeared to have been interred as part of some ancient ritual. But this wasnt what people would talk about in the surrounding villages, where the alchemy of rumor was bound to transform the coins from bronze to gold, and the statues from modest pieces to relics as valuable as Tutankhamuns funerary mask. The worst-case scenario would be for such a discovery to be followed by some breakdown in civil order. But there was no reason to expect that this might occur. President Hosni Mubarak had ruled Egypt for almost thirty years, and protests in the capital rarely affected remote parts of the country.

On January 26, 2011, the second day of the Egyptian Arab Spring, nothing happened in Abydos.

The archaeologists had been working to the west of the local settlements, in an ancient necropolis that villagers refer to as al-Madfuna: the Buried. The Buried contains the earliest known royal graves in Egypt, and its also home to one of the oldest standing mud-brick buildings in the world. This structure dates to around 2660 BC , with nearly forty-foot-high walls that form a massive rectangular enclosure. Nobody is certain of its original purpose. The local Arabic nameShunet al-Zebib, Storehouse of Raisinsis another mystery. At various times, people have speculated that it was once a depot for goods or animals. Auguste Mariette, a French archaeologist who worked here in the middle of the nineteenth century, suggested without citing any evidence that the structure had been a sort of police station. This theory seems to have been a projection of Mariettes concerns about looting, which has been a problem in Abydos for approximately five thousand years.

On January 28, 2011, in Cairo, on the fourth day of the Egyptian Arab Spring, tens of thousands of people gathered in Tahrir Square, and somebody set fire to the nearby headquarters of Mubaraks National Democratic Party.

In Abydos, the team from Brown University had already returned home, and now another group of archaeologists had arrived from the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. This group was restoring parts of the Shunet al-Zebib, or the Shuna, as the structure is usually called. The NYU team was led by an archaeologist named Matthew Adams. He was forty-eight years old, and he had the well-cooked appearance of any Westerner who has spent a career in the Sahara. His ears and cheeks were red, and the shadow of his shirt line had been permanently burned into his neck and chesta V-shaped hieroglyph that means Egyptologist.