Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

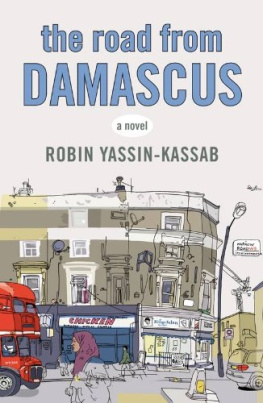

Enlightenment on the Eve of Revolution

ENLIGHTENMENT ON THE EVE OF REVOLUTION

The Egyptian and Syrian Debates

ELIZABETH SUZANNE KASSAB

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK CITY

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2019 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54967-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kassab, Elizabeth Suzanne, author.

Title: Enlightenment on the eve of the revolution : the Egyptian and Syrian debates / Elizabeth Suzanne Kassab.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018048838 | ISBN 9780231176323 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231176330 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: EgyptIntellectual life20th century. | EgyptIntellectual life21st century. | SyriaIntellectual life20th century. | SyriaIntellectual life21st century. | Islam and secularismEgypt. | Islam and secularismSyria. | Islam and stateEgypt. | Islam and stateSyria. | Civil societyEgypt. | Civil societySyria. | EnlightenmentEgypt. | EnlightenmentSyria.

Classification: LCC DT107.826 .K37 2019 | DDC 962.05/5dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018048838

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

Cover image: Elias Zayyat, Deluge: The Gods Abandon Palmyra: Study 01 , 2003. Courtesy of the Atassi Foundation for Art and Culture.

Contents

When my previous book, Contemporary Arab Thought: Cultural Critique in Comparative Perspective , came out in 2010, I had no idea that a momentous upheaval would shake much of the Arab world before the end of that year. Yet the book had laid bare an unmistakable alarm and discontent among intellectuals about how regimes and societies were faring in the Arab world. This discontent was largely about the failures of the postindependence states to secure a functional political life, healthy economic development, basic health care and education, freedom of expression, civil and human rights, and some hopeful future for its citizens. My analysis showed deep frustration at the enduring impossibility of change, but it could not foresee the large-scale outburst of that accumulated frustration and anger.

Like so many others who followed the massive protest movements that broke out in December 2010 in Tunisia and then spread to Egypt, Syria, Yemen, and Morocco during 2011, I became glued to my computer as I pursued the exhilarating albeit increasingly distressing developments across the Arab countries. My focus was on the intellectual debates that accompanied those developments and the attempts of Arab intellectuals and artists to make sense of what they were witnessing. I was also interested in situating those debates in contemporary Arab intellectual history, and in particular in the three decades that preceded the 20102011 upheavals.

This book is an attentive reading of two sets of debates on tanwir (enlightenment in Arabic) that took place in Cairo and Damascus in the 1990s and 2000s. My aim is to situate these debates in the Arab intellectual history of the second half of the twentieth century and leading up to the 2011 upheavals. I argue that these debates addressed the mounting failures of the postindependence states and that what they advocated under the name of tanwir was a form of political humanism. They called for the reconstruction of the human being in Arab societies, for the affirmation and protection of life and human dignity, for the assertion of peoples right to political participation and civil mobilization, and for the invention of hope and faith in the human in the midst of despair. I also argue that by warning against the consequences of the state failures and asking for urgent change, they voiced demands that were to be heard a decade or two later in the streets of Cairo and Damascus.

Work on this book was generously supported over many years by German research centers. In spring and fall 2011, Gudrun Krmer hosted me as a fellow researcher at the Berlin Graduate School Muslim Cultures and Societies of the Free University. In weekly meetings organized with rigor and generosity by Professor Krmer, the school offered a lively and diverse forum for fellows to exchange research notes. It presented pleasant and optimal work conditions in the quiet and leafy Dahlem neighborhood of Berlin. It also allowed me to benefit from the rich network of academic centers across the Free University and beyond.

During the 20132014 academic year, I was offered a fellowship at the Kte Hamburger Center for Advanced Study in the Humanities in Bonn, an idyllic location and a haven for researchers. I thank Stefan Wild for recommending me to the center and for the many conversations we had during my stay in Bonn. The centers founding director, Werner Gephart, with his accomplished scholarly and artistic gifts, offered a welcoming setting in an atmosphere of conviviality, freedom, and intellectual erudition. The centers manager, Stefan Finger, and his team of young scholars and student assistants provided sustained, competent, and friendly support throughout my stay. And last but not least, the centers physical location on the majestic Rhine was a constant invitation for peaceful meditation and productive conversations, a most precious opportunity for those of us who hailed from the convulsive parts of the Arab world. For me, coming from Lebanon and working on the Arab world, it was a cherished safe setting at a comforting distance from the events unfolding in the east of the Mediterranean. After hours of following daily news and commentary on my office computer, I would lift my eyes and see from the window the tranquil flow of the Rhine, and I would ponder on how so much violence and serenity could coexist on the same planet. The contrast was unfathomable to me. I knew of the unspeakable horrors that had taken place on the banks of that clean and beautiful river, and I was often reminded of the barbaric propensity common to humanity. During my walks on the banks, I would pass by postwar Germanys old and modest house of parliament and think of the long and arduous journey of the new republic toward democracy. It is true that that journey was supported by foreign powers whose interest lay in bringing about a stable and pacified Germany, but it also involved the tremendous efforts of the Germans to pull themselves out of the moral, political, and economic ruins of their country. Public debates regarding this dramatic past continue to mark the country, and their intellectual, moral, and political quality remains a source of inspiration for me.

My stay in Bonn was extended by another semester when I was invited to be the Annemarie Schimmel Visiting Professor at the University of Bonn for spring 2015, during which I gave a seminar on the Arab nahda (or renaissance). I thank the students with whom I had interesting discussions about those past nahda debates, often in connection with the issues that were being raised by Arab thinkers as the uprisings were unfolding.

In fall and winter 20152016, I was a fellow at the Centre for Middle East Studies at the University of Marburg, in a program launched after the Arab revolutions entitled Re-configurations: History, Remembrance and Transformation Processes in the Middle East and North Africa, with a hub of international scholars working on those reconfigurations. The interaction with local and visiting scholars and the wonderful research facilities helped me progress with my manuscript. I thank Rachid Ouissa, head of the Re-configuration program, and its director, Achim Rohde, for hosting me. I was then invited to join the Leibniz Research Group Figures of Thought-Turning Points: Cultural Practices and Social Change in the Arab World, headed by Friederike Pannewick at the University of Marburg. I thank Professor Pannewick for her warm support. During those two years, 2015 and 2016, the refugee flow from Syria, Iraq, Eritrea, and elsewhere in and around the Middle East reached unprecedented levels since World War II, with people desperately seeking safety and a glimmer of hope for their future. Exposing themselves to the murderous exploitation of traffickers and the hardships of the Mediterranean and Balkan routes, thousands of people lost their own lives or lost loved ones and precious belongings. Most of them wanted to reach Europe, and Germany in particular, and in so doing challenged the proclaimed values and unity of the continent, provoking a serious European crisis whose aftermath is still being felt today. I attentively followed the debates that ensued from this crisis in and outside Germany.