Revolutionary Ideas

Revolutionary Ideas

AN INTELLECTUAL HISTORY OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION FROM THE RIGHTS OF MAN TO ROBESPIERRE

Jonathan Israel

Princeton University Press

Oxford & Princeton

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

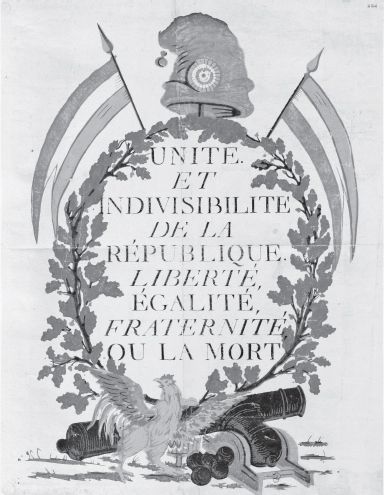

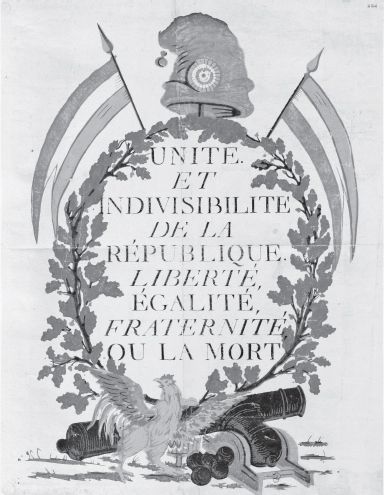

Frontispiece: The unity and indivisibility of the Republic, 1793. Image courtesy Bibliothque nationale de France.

Jacket illustration: Allegorical emblem of Republic Fasces topped by Cap of Liberty and ribbands with legend, Liberty, Fraternity, Egality, or Death. French Revolution 1789, contemporary popular colored print. Courtesy Image Asset Management Ltd. / Superstock.

All Rights Reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Israel, Jonathan.

Revolutionary ideas : an intellectual history of the French Revolution from the Rights of Man to Robespierre / Jonathan Israel.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15172-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. FranceHistoryRevolution, 1789-1799Causes. 2. FranceHistoryRevolution, 1789-1799Historiography. 3. FranceIntellectual life18th century. 4. RevolutionariesFranceHistory18th century. I. Title.

DC147.8.I87 2014

944.04dc23

2013018208

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Garamond Pro and Pastonchi

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Contents

Figures

Acknowledgments

In writing any work of scholarship, one incurs a large number of debts. For vigorously debating the themes of this book with me, I would like especially to thank Peter Campbell, Aurelian Craiutu, David Bell, Jeremy Popkin, Ouzi Elyada, Harvey Chisick, Steven Lukes, Nadia Urbinati, David Bates, Pasquale Pasquino, Bill Doyle, Helena Rosenblatt, Bill Sewell, and Keith Michael Baker. For unflagging and invaluable help with the bibliography, finding eighteenth-century texts, obtaining the illustrations, and checking details, my thanks are due especially to Maria Tuya, Terrie Bramley, and Sarah Rich. I was hugely helped at the last stage also by my copy editor at Princeton University Press, Cathy Slovensky. In addition, a special debt of gratitude is owed by me to the library staff at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, and to the Institute itself for being supportive in every respect and in every way an optimal place to reflect on historical research and debate, and to think and write to the best of ones ability.

Finally, for immense and unstinting assistance throughout with editing, checking, and helping to finalize the text (as well as putting up uncomplainingly with my endless talk about the Revolution and its personalities in recent years), it is a particular pleasure to add that I owe a very great deal, more than I can possibly say, to my wife, Annette Munt.

Revolutionary Ideas

Prologue

On November 18, 1792, more than one hundred British, Americans, and Irish in Paris gathered at Whites Hotel, also known as the British Club, to celebrate the achievements of the French Revolution. While in general British opinion, encouraged by the London government and most clergy, remained intensely hostile to the Revolution, much of the intellectual and literary elite of Britain, the United States, and Ireland was immensely, even ecstatically, enthusiastic about those achievements and determined to align with the Revolution. Although the later renowned feminist Mary Wollstonecraft only arrived at Whites shortly afterwardand Coleridge, during the 1790s, another fervent supporter of the new revolutionary ideology, was absentthose attending formed an impressive group. Present were Tom Paine, author of the Rights of Man (1791); the American radical and poet Joel Barlow; several other poets, including Helen Maria Williams, Robert Merry, and possibly Wordsworth; the Unitarian minister and democrat David Williams, author of the Letters on Political Liberty (1782); a former member of Parliament for Colchester, Sir Robert Smyth; the Scots colonel John Oswald; the American colonel Eleazar Oswald; and the Irish lord Edward Fitzgerald. It was a sharp reminder that, leaving aside Gibbon and Edmund Burke, distinguished and politically aware British, American, and Irish intellectuals, poets, and authors, like their German and Dutch counterparts at that time, mostly endorsed and applauded the Revolution.

The president of the British Club in Paris at the time was John Hurford Stone (17631818), a former London coal merchant originally from Somerset, and a friend of such leading British democratic reformers as Joseph Priestley and Richard Price (both great enthusiasts for the French Revolution). Hurford Stone had settled in Paris where he owned a chemical works and a printing press with which he produced materialist and antitheological texts, including those of Paine and Barlow. He was a close ally of both Paine and Barlow, the latter a Yale graduate, some editions of whose vast American epic, The Vision

The high point of the daylong banquet on 18 November 1792, to which delegations from several other nations were also invited, was sixteen toasts: the first, to the French Republic embodying the Rights of Man (here the trumpets of the German band played the famous revolutionary tune a Ira); the second, to the armies of France (may the example of her citizen soldiers be followed by all enslaved nations until all tyranny and all tyrants are destroyed; the German band played the recently composed Marseillaise, soon to be proclaimed the Republics official national anthem); the third, to the achievements of the French National Convention; and the fourth, to the coming constitutional Convention of Britain and Ireland. Here came a hint of the clubs subversive intent, as it agreed not just that Ireland had been unjustly enslaved by England but that Britain too needed a democratic revolution akin to that in France.

The fifth toast was raised to the perpetual union of the peoples of Britain, France, America, and the Netherlands: may these soon bring other emancipated nations into their democratic alliance; the sixth, to the prompt abolition in Britain of all hereditary titles and feudal distinctions. This toast was proposed by Sir Robert Smyth (17441802), former MP for Colchester, and Lord Edward Fitzgerald (176398), a dashing Irish noble and friend of Paine who held the rank of major in the British army and later became a principal plotter in the United Irishmen Conspiracy of 179698. Fitzgeralds and Smyths total repudiation of aristocracy was greeted with outrage in England when reported in the papers soon afterward, leading to the former being cashiered from the British army and the latter being firmly ostracized. On the eve of the Irish uprising of 1798 (which was vigorously suppressed amid terrible slaughter), Fitzgerald was killed in a fray with British officers who broke into his Dublin lodgings to arrest him.

Next page