Contents

Revolution

Revolution

An Intellectual History

Enzo Traverso

First published by Verso 2021

Enzo Traverso 2021

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-333-5

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-360-1 (UKEBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-361-8 (USEBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021941136

Typeset in Fournier by MJ&N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

MECW = Marx, Engels, Collected Works, London: Lawrence & Wishart, 19752005, 50 vols.

LCW = Lenin, Collected Works, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 196070, 45 vols.

WBSW = Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, Michael Jennings (ed.), Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 200306, 4 vols.

T his book has greatly benefited from a sabbatical year at Cornell University. The Covid-19 pandemic changed my plans and I had to cancel several research-stays in Europe, notably in Paris and Berlin, but in the end the isolation I was forced to endure in Ithaca, New York, proved a fruitful retreat, profitable to introspective meditation and writing on history. It was a good opportunity for working through many ideas and experiences: the ideas I have encountered, adopted, defended or criticized in the past; and the experiences I have accumulated in my life, from my first political commitments in the 1970s to the intellectual debates of the twenty-first century. I never participated in a revolution except for having lived during a time when revolution was in the air but many questions and dilemmas which I try to reconstitute and analyse in this book have also been mine. Thus, if my views have changed on many issues, there is no doubt that writing this book solicited my recollections and frequently resonated with my lived experience. However, I have not written it as a witness or in order to come to terms with the past; I am not adopting any apologetic posture or trying to settle my accounts with adversaries or critics. I simply feel part of the history I tell, burdened as it was with utopias, generosity, fraternity, and greatness, but also with mistakes, illusions, deceptions, and sometimes monstrosities. Writing on the history of revolutions requires awareness of the dangers of subjectivity, which cannot be repressed but needs to be managed, controlled, and mastered. I remember an interesting conversation with Tzvetan Todorov a thinker I respected, despite our considerable disagreements in which we both admitted that Italians and Bulgarians cannot look at the history of communism through a similar lens, simply because they are located in very different observatories and communism does not mean the same thing in their respective countries. I do not know whether I have been able to make a proper and fruitful use of my existential background, which is limited and emphatically particular, by both keeping it at a necessary distance and mobilizing it as an analytical tool, but I do know that this exercise requires humility and modesty. With regard to revolution, too often critical understanding has been replaced by nave enthusiasm, moral judgement or ideological stigmatization. These are not the options I have chosen, and my book does not pretend to transmit the lessons of the past; it is simply an attempt at critical knowledge and interpretation. This is the main task that my generation can accomplish today.

Writing this book, I realized how much I was indebted towards friends, comrades, scholars, and authors: those with whom I have had fruitful discussions, as well as those whom I have never met but whose works have nonetheless accompanied me on my intellectual journey. Classical thinkers and original scholars, but also unknown, rank-and-file activists whom I encountered in several countries and at several different times: all of them mattered to me. It would take too long to mention them here, but I am grateful to all of them.

This book was born from a couple of graduate seminars which I had the pleasure to teach in recent years at Cornell University and, in a more condensed form, at other universities in both Europe and Latin America, notably the University of San Martn and the CeDInCi in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in November 2018; and the University of Valencia, Spain, in January 2020. I am very grateful to my students, as well as to the colleagues and good friends who invited me to share and discuss my ideas: Horacio Tarcus and Nicols Sanchez Dur. Singular chapters have been presented as lectures, keynote speeches, or discussed as papers in seminars at several universities and cultural societies: the University of Rome 3, in January 2018; Jour Fixe Lectures, Berlin, June 2017; the Free University of Brussels, October 2017; the University of Texas, Austin, April 2019; the University Rio appeared in Spanish with the title El tortuoso camino de la libertad in La Maleta de Portbou, 38 (2019). Written in English, this book benefited significantly from the linguistic revision and critical reading by Nicholas R. Bujalski and William R. Cameron, my valuable research assistants at Cornell University, whom I thank. At Verso, Lorna Scott Fox was a remarkable copyeditor, and I am very grateful to her. The support from my editor, Sebastian Budgen, was essential from the beginning.

Ithaca, NY, April 2021

Interpreting Revolutions

Proletarian revolutions constantly engage in self-criticism, and in repeated interruptions of their own course. They return to what has apparently already been accomplished in order to begin the task again; with merciless thoroughness they mock the inadequate, weak and wretched aspects of their first attempts; they seem to throw their opponent to the ground only to see him draw new strength from the earth and rise again before them, more colossal than ever; they shrink back again and again before the indeterminate immensity of their own goals.

Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852)

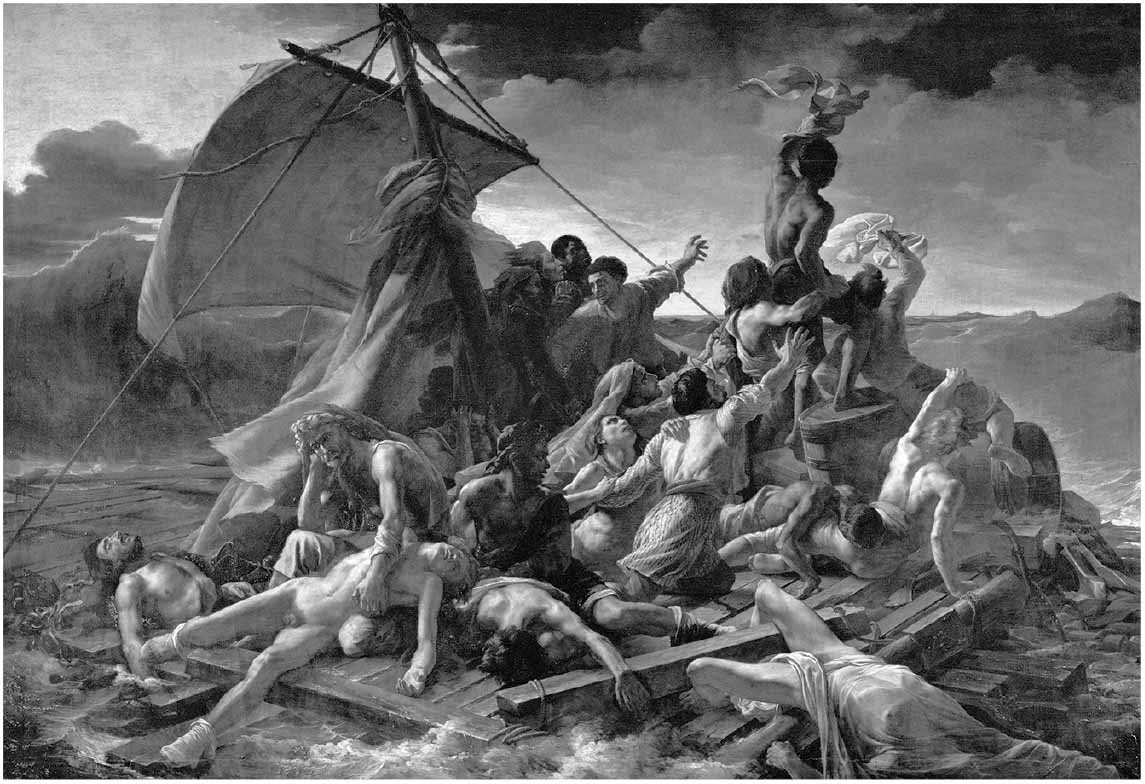

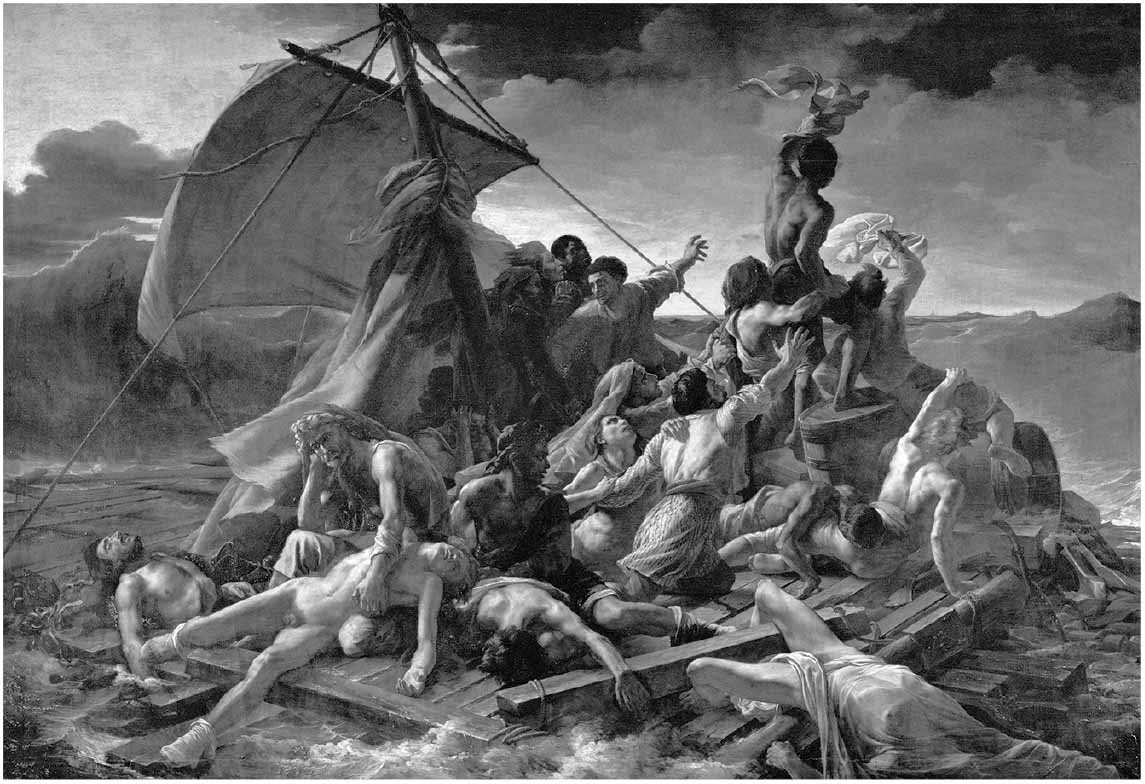

M any years ago, leaving an exhibition at the Louvre Museum just before closing time, I suddenly found myself in an empty room all other visitors had already left in front of Thodore Gricaults The Raft of the Medusa (1819). The impact of that striking moment has endured, and I still have a clear memory of what I felt. Of course, I knew this painting, one of the most famous works of nineteenth-century romantic art, but this unexpected meeting revealed to me a completely unknown piece: I was admiring one of the most powerful allegories of the shipwreck of revolution. Not only the French Revolution, the only one the painter could think about when making his masterpiece, but also and above all the revolutions of the twentieth century, which had just passed away at the time of my Louvre visit. Many details of this monumental canvas achieved a clear meaning to me when related to modern revolutionary history.