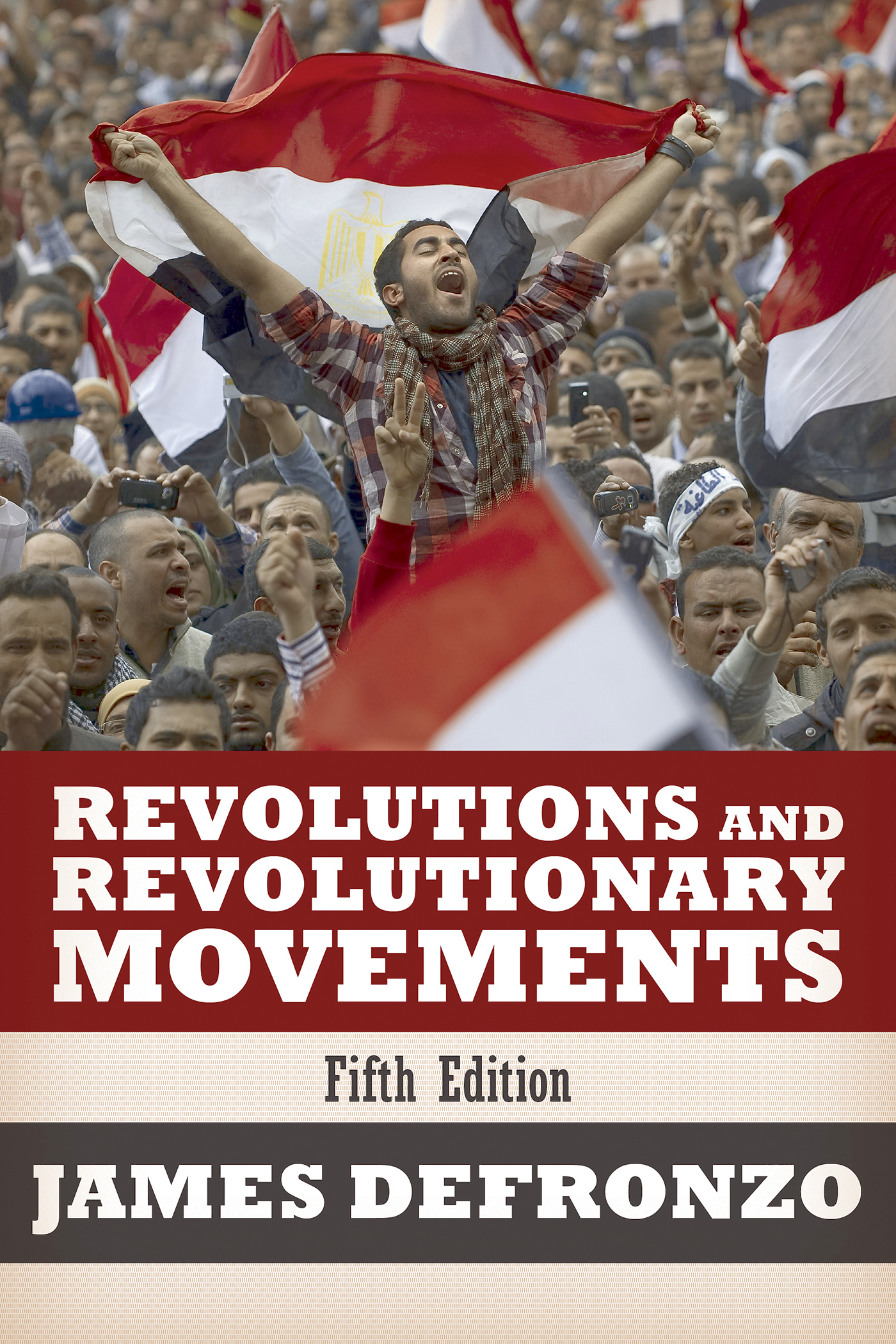

Revolutions and Revolutionary Movements

Revolutions

and

Revolutionary

Movements

Fifth Edition

James DeFronzo

University of Connecticut

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

Westview Press was founded in 1975 in Boulder, Colorado, by notable publisher and intellectual Fred Praeger. Westview Press continues to publish scholarly titles and high-quality undergraduate- and graduate-level textbooks in core social science disciplines. With books developed, written, and edited with the needs of serious nonfiction readers, professors, and students in mind, Westview Press honors its long history of publishing books that matter.

Copyright 2015 by Westview Press

Published by Westview Press,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Westview Press, 2465 Central Avenue, Boulder, CO 80301.

Find us on the World Wide Web at www.westviewpress.com.

Every effort has been made to secure required permissions for all text, images, maps, and other art reprinted in this volume.

Westview Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Designed by Jack Lenzo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

DeFronzo, James.

Revolutions and revolutionary movements / James DeFronzo.Fifth edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8133-4925-1 (e-book) 1. Revolutions. 2. Social movements. 3. RevolutionsCase studies. 4. World politics20th century. 5. World politics21st century. I. Title.

HM876.D44 2015

303.64dc23

2014016782

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Maps

Preface

A public that knows little about the political history and socioeconomic characteristics of other societies may permit its government to control how citizens perceive its actions in foreign lands. It is possible, for example, that US involvement in Vietnam would not have occurred or at least would not have progressed as far as it did if the American people had been fully aware of the Vietnamese revolution against French colonial rule, the loss of popular support for Frances Indochina war effort, and the terms of the resulting Geneva peace settlement of 1954. Similarly, if the profound differences and conflicts between Iraqs Baath Party and the Islamic fundamentalist movement Al Qaeda had been more widely known in the United States, the American people would have been less likely to believe that Iraq was involved in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, or to support the 2003 invasion of Iraq. New revolutionary movements and related conflicts have emerged in the Middle East, North Africa, and other places around the globe that once again tempt other countries, including the US, to consider intervention.

Although the US public was too poorly informed to prevent the tragedy in Vietnam, the collective memory of the Vietnam experience probably helped prevent direct US military intervention in several countries. But key elements of the Vietnam experience were apparently not passed on to post-Vietnam generations. This became clear to me through the responses I received to a question I asked students in several large sociology classes. The question was, How many of you have had any treatment of the Vietnam conflict in high school? In each case, less than 5 percent raised their hands! Most of them also indicated on anonymous questionnaires that they knew very little about social movements and political conflicts in other parts of the world. I found this disturbing because most of them were college juniors and seniors preparing to embark on their careers and take on their future political and social responsibilities.

There are probably several reasons why many Americans lack political knowledge of other societies. As citizens of the richest and most technologically advanced nation in the world, many of us feel little need to concern ourselves with the politics of less developed countries or to become familiar with the traditions of other cultures. Many people shy away from political topics because they want to avoid controversy. The fear of conflict over how to deal with the subject of Vietnam would have been especially acute in a high school faculty, with some faculty members being war veterans and others antiwar activists. In such a scenario this potentially explosive topic would have been avoided in history and social science classes. The same thing may be occurring with regard to the Iraq War.

The mass media, like the educational system, have often failed to provide information about foreign societies to the vast majority of the American people. Television networks, in the competition for advertising dollars, are intent on maximizing viewer ratings. Programs dealing with political topics in other lands cannot usually command a respectable percentage of the viewing public (except in times of war or other international emergencies such as the period immediately following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, or during the Iraq War that began on March 20, 2003, or during the threat of US military intervention in Syria in 2013).

Yet when they are given a chance, many people display a strong interest in learning about political events and conflicts in other parts of the world. I have noted this in a course I have taught, Revolutionary Social Movements Around the World. Using lectures and documentaries, I attempt to explain the development and significance of important twentieth- and twenty-first-century revolutionary movements and associated political conflicts in Russia, China, Vietnam, Cuba, Central American nations, Iran, South Africa, Venezuela, nations of the Middle East, and other countries. Beginning in the mid-1980s class size often exceeded two hundred students, with about one-third of the enrollment drawn from outside the University of Connecticuts College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (i.e., from the colleges of business, engineering, nursing, education, and others; engineering and nursing students were often the best students in the course). According to surveys of class enrollees, the course attracted so much interest because it provided students an opportunity to learn about a significant number of political conflicts (and the societies in which they occur) in a single course. I hope to provide a similar opportunity to a wider audience through the fifth edition of this book.

In the first chapter, the reader is introduced to factors important for the discussion of modern revolutions, such as the development of revolutionary conditions, relevant theoretical perspectives, the roles of leaders, the functions of ideology, and the meaning of important concepts such as socialism, communism, nationalism, ideology, peoples war, guerrilla warfare, and counterinsurgency, which are employed in specific contexts throughout the book. The revolutions, revolutionary movements, and conflicts covered include those of greatest world significance and those of central importance to the development of revolutionary ideology, strategy, and tactics in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.