Copyright 2017 by Ken Lizzio

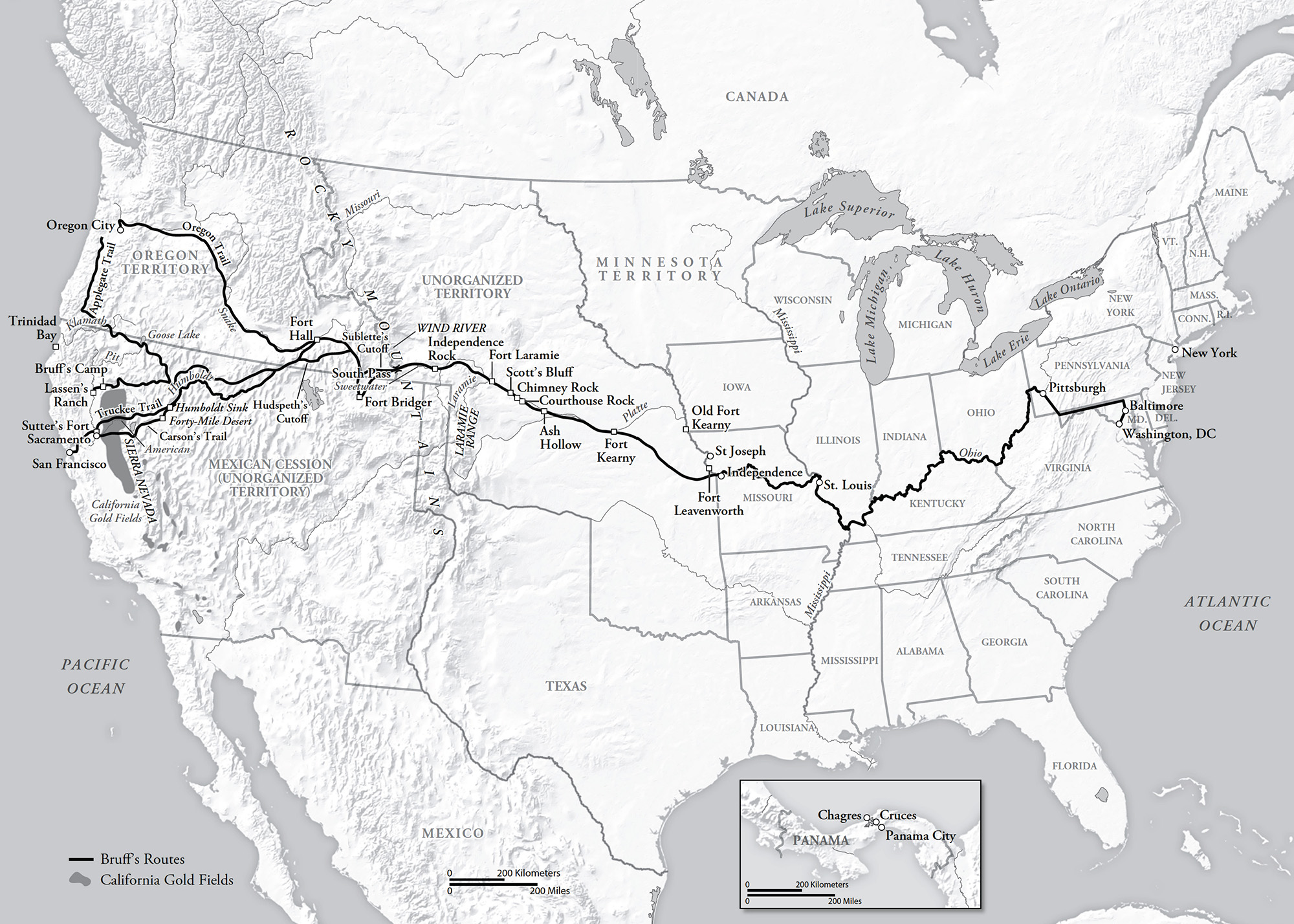

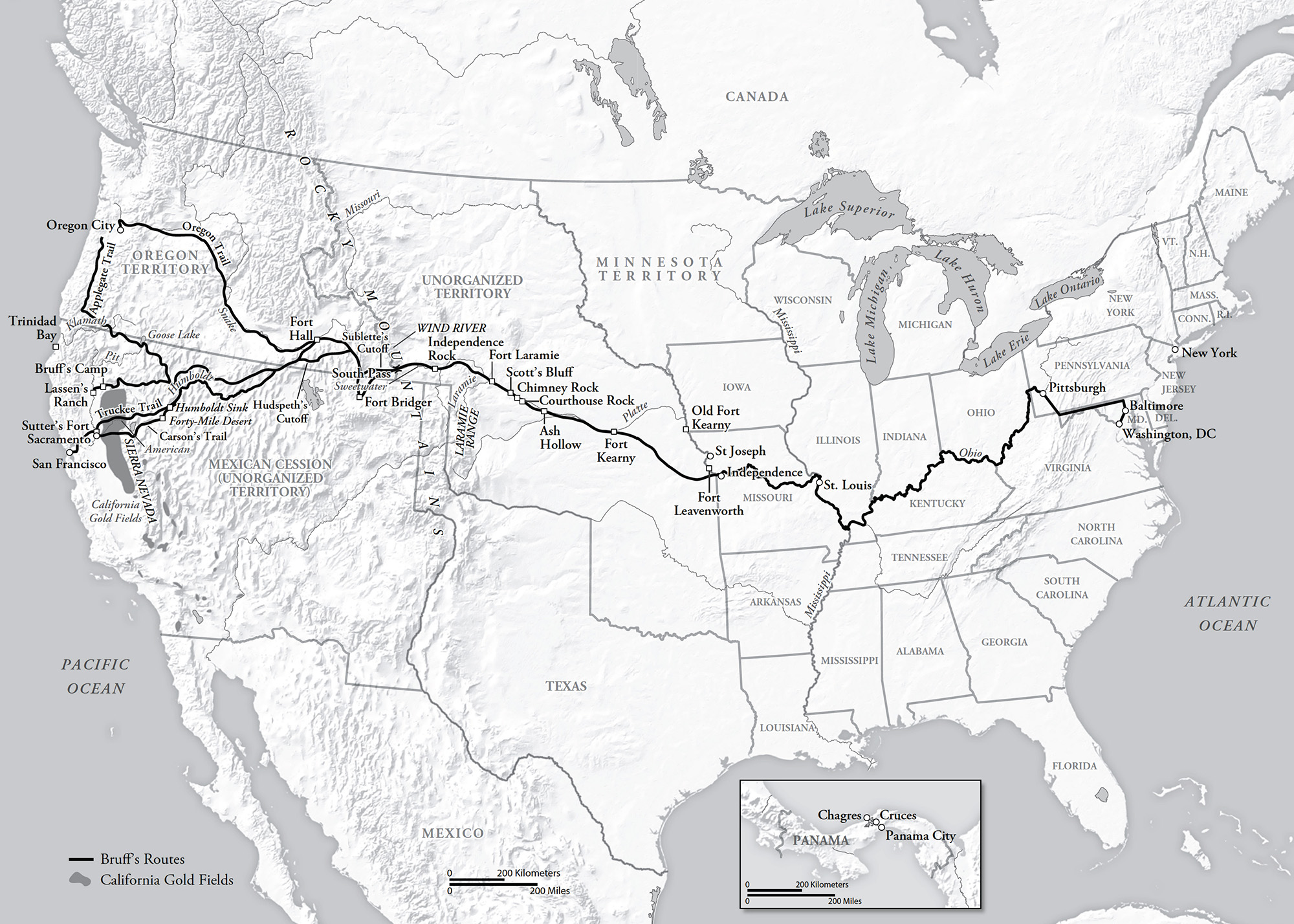

Maps Copyright 2017 by The Countryman Press

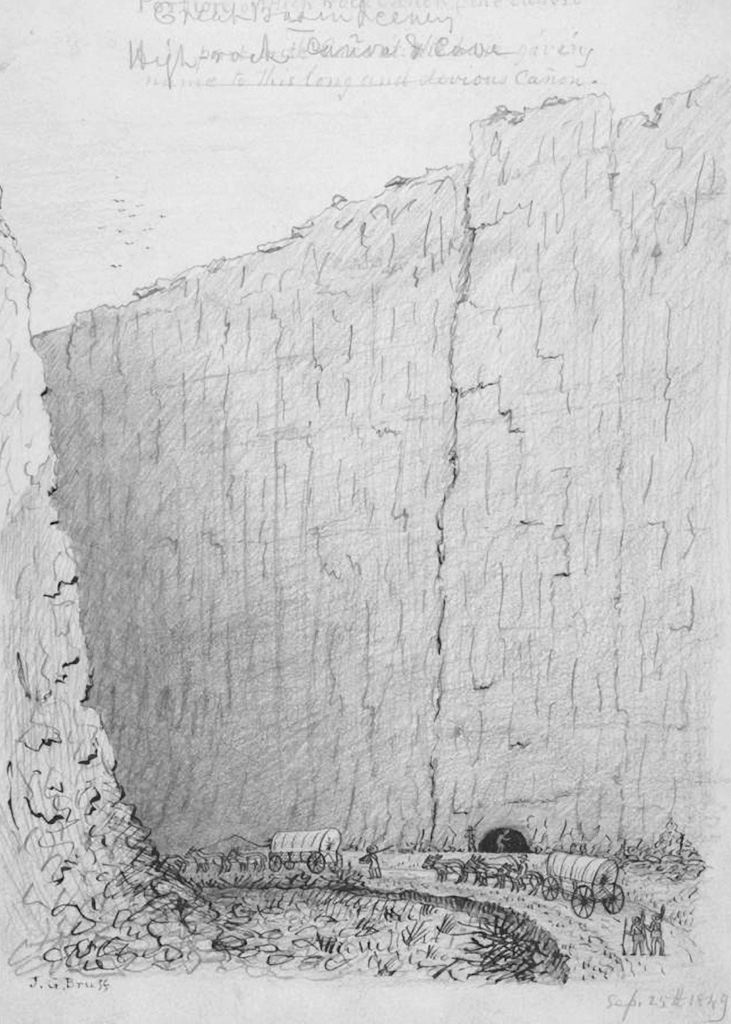

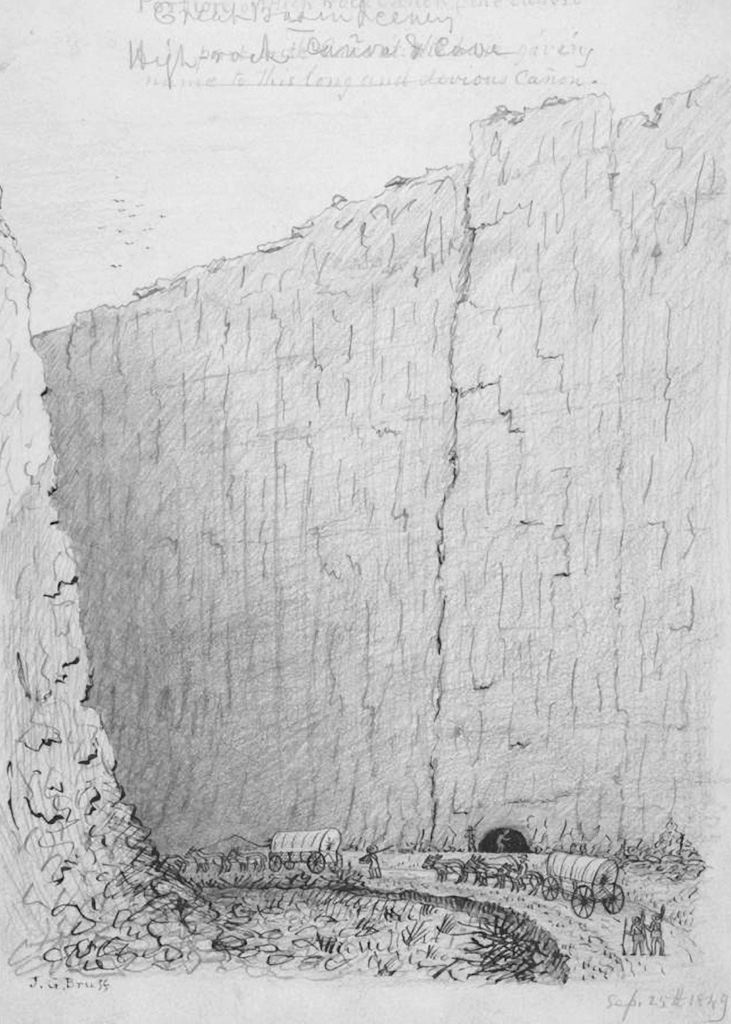

Drawings courtesy of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, The Countryman Press, 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Lovedog Studio

Production manager: Devon Zahn

Cover image: Coloured engraving, American School (19th century) / Private Collection / Peter Newark Western Americana /

Bridgeman Images

The Countryman Press

www.countrymanpress.com

A division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

www.wwnorton.com

978-1-68268-050-6

978-1-68268-051-3 (e-book)

Hurrah for a trip oer the plains,

No matter for clouds and rains,

Go ahead is the order that rules!

J. Goldsborough Bruff

At our house at Burlington, we had a nice yard, and plum trees, and peaches, and gooseberries: and we could go a little ways, and get all them things. Oh, how I miss em!

Billy, 6-year-old emigrant boy

I wish California had sunk into the ocean before I had ever heard of it.

James Wilkins, California 49er

I FIRST DISCOVERED THE REMARKABLE STORY OF Joseph Goldsborough Bruff, or J. Goldsborough Bruff as he preferred to sign himself, in Theodora Kroebers Ishi in Two Worlds. Bruff never met Ishi, the celebrated last wild Indian in North America, having left California a decade before Ishi was born. Their connection lay in the fact that on his way to the California gold fields in the winter of 1849, Bruff became marooned in the High Sierras in the territory of Ishis forebears, the Yahi.

That year Bruff was one of nearly 90,000 individuals, American as well as foreign, who caught the gold fever and hastened over land and sea to California. Over the next four years, at least another 300,000 would make the journey in search of adventure, fortune, and a better life. Yet it was the first wave of Americans who went overland in 1849some 35,000 of themthat came to define the California Gold Rush. The 49ers were among the very first Americans to see and experience the American frontier with its primitive Indians and other natural curiosities such as the shaggy buffalo and the antelope. The tallgrass prairie, vast deserts, and soaring mountains described by early explorers promised landscapes unlike anything to be found in the East. For Bruff and countless other emigrants, the journey was expected to be an adventure every bit as exciting as the quest for gold.

Like dozens of other emigrants that year, Bruff kept a journal of his experiences along the emigrant trail and in the gold fields. That his journal is regarded as one of the most detailed and comprehensive that came out of the Gold Rush era makes it puzzling why his extraordinary story has never been told in its entirety, as Kroeber herself wondered.

By any measure, J.G. Bruff was an extraordinary man. A sailor, mapmaker, artist, writer of light verse, amateur geologist, Bruff could seemingly do anything and was interested in everything. He belonged to the Metropolitan Mechanics Institute and the Washington Monument Association. He served as Recording Secretary of the National Art Association before which he presented two papers and was a member of the National Institution for the Promotion of Science.

With such an open and inquisitive mind, Bruffs journal makes the perfect guide for life on the Gold Rush trail. With a keen eye for detail, each day he recorded meteorological data, the flora, fauna, and minerals of each region, and his experiences on the trail and in the gold fields. Over the course of the journey, with quill and inkpot, he made entries each day in a neat hand, an extraordinary accomplishment considering the arduous conditions of the trail, particularly the frigid Sierra winter. He made entries in his journal every day, testimony to his strength of will and character. He also drew more than 300 sketches of landscapes and aspects of life on the trail, many of which were the very first scenes of the American frontier such as the northern California coastline and the Klamath Indians.

As Captain of the Washington, DC, Gold Mining Company, Bruff also ably led a large party of men across the dangerous and unfamiliar American frontier. His insistence on leading his party in the manner of a military expedition was unusual, but it proved key to the groups success. Day after day he resolved problems along the trail demonstrating wisdom, fairness, and above all concern for the welfare of his men and other travelers on the trail. At the end of each day, while the other men were resting from the days exhausting march, the indefatigable Bruff was laying out the next days trip and making entries and sketches in his journal by the light of the campfire. He reveled in his military role, however artificial, precisely because the real thing had tragically been denied him by lifes circumstances.

As commander of the expedition, Bruff enforced a strict discipline that enabled him to keep a very diverse and at times fractious group of men together all the way to California. For this accomplishmentand this is what makes his story uniquehe was repaid in the rudest of specie by his men: abandonment. Some of the men who resented being treated as subordinates left Bruff to starve in the High Sierras. Even the men who respected and supported Bruff showed little concern for his welfare that winter, so anxious were they to get to the gold fields. Such was the wanton selfishness that the Gold Rush inspired in almost everyone.

Bruff responded to the betrayal by his men in the same way he responded to that impossible and solitary winter in the Sierras: with stoicism, optimism, and generosity. Even as he struggled with hunger and his own failing health, he never stopped assisting hundreds of gold seekers worse off than himself. Whether they knew it or not, many of them owed their lives to the extraordinary man from Washington. Yet time and again, the very people he had helped selfishly disregarded his own pleas for assistance in getting off the mountain.

Bruff told his wife he would be gone for eight months and did not return for more than two years. During all that time, he faithfully recorded an entry in his journal every day on the trail, come hell or high water. Indeed, that many of those days were hell testified to a tragic truth about the Gold Rush: For many, if not most emigrants, the Gold Rush was a bust. Some never made it to California, having turned back or perished along the way from disease, accident, Indian attack, even suicide. If they were lucky enough to have made it to California, they usually had little luck in finding gold. Most returned to their previous lives disappointed, dispirited, and poorer for the experience.

Not Bruff, however. Even though he, too, failed to find gold, he turned his arduous journey into a trove of information and illustrations of the great American West that became a priceless treasure to those who followed him. In the end, it became the gold he mined.

FORTY-NINER

Next page