Bruno Giordano - Giordano Bruno: Philosopher of the Renaissance

Here you can read online Bruno Giordano - Giordano Bruno: Philosopher of the Renaissance full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Taylor and Francis Ltd : Routledge, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Giordano Bruno: Philosopher of the Renaissance

- Author:

- Publisher:Taylor and Francis Ltd : Routledge

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Giordano Bruno: Philosopher of the Renaissance: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Giordano Bruno: Philosopher of the Renaissance" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Giordano Bruno: Philosopher of the Renaissance — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Giordano Bruno: Philosopher of the Renaissance" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno

Philosopher of the Renaissance

Edited by

HILARY GATTI

First published 2002 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Hilary Gatti and the contributors, 2002

The authors have asserted their moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Giordano Bruno: Philosopher of the Renaissance.

1. Bruno, Giordano, 15481600. 2. Philosophy, Renaissance.

3. Philosophy, Italian.

I. Gatti, Hilary.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2001099632

ISBN 13: 978-0-7546-0562-1 (hbk)

Contents

Giovanni Aquilecchia

Lars Berggren

Maurice A. Finocchiaro

Ingrid D. Rowland

Lina Bolzoni

Hilary Gatti

Tiziana Provvidera

Michael Wyatt

Elisabetta Tarantino

Leen Spruit

Stephen Clucas

Ramon G. Mendoza

Ernesto Schettino

Leo Catana

Paul Colilli

Andrew Gregory

Stuart Brown

Paul Richard Blum

.

.

Giovanni Aquilecchia, formerly of University College London

Lars Berggren, University of Lund, Sweden

Paul Richard Blum, Peter Pazmany University, Budapest

Lina Bolzoni, Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa

Stuart Brown, Open University, Milton Keynes

Leo Catana, University of Copenhagen

Stephen Clucas, Birkbeck College, University of London

Paul Colilli, Laurentian University, Canada

Maurice A. Finocchiaro, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Hilary Gatti, University of Rome La Sapienza

Andrew Gregory, University College London

Ramon G. Mendoza, Florida International University

Tiziana Provvidera, University College London

Ingrid D. Rowland, Andrew Mellon Chair, American Academy in Rome

Ernesto Schettino, National University of Mexico

Leen Spruit, University of Rome La Sapienza

Elisabetta Tarantino, Oxford Brookes University

Michael Wyatt, independent scholar

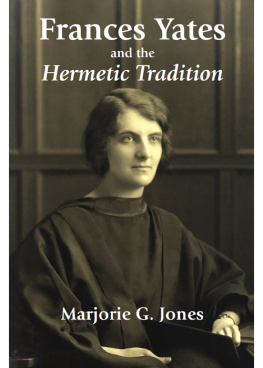

Giordano Bruno has been depicted in many ways in the course of the four centuries which separate us from his tragic death, burnt as a heretic in the Campo dei Fiori (The Field of Flowers) in Rome on 17 February 1600. For some he has been a prophet of the new science, who first supported and then extended to infinity the still suspect Copernican, heliocentric astronomy; for others a practitioner of a vividly symbolic and imaginative version of the classical art of memory; an inspiring or dangerous libertin rudit, according to the point of view being proposed; or a metaphysician or mystic with a rich talent for expressing his vision of God in complex and moving verse. More recently he has been depicted as a Renaissance version of an ancient Egyptian or Hermetic Magus, according to an influential reading proposed by the late Dame Frances Yates.

Bruno, however, defined himself constantly and coherently as a philosopher: a definition to which he repeatedly resorted during his eight-year long trial at the hands of first the Venetian and then the Roman Inquisition. For Bruno saw his trial as a struggle for the right of the philosopher to follow a line of thought to its logical conclusion, whatever objections might be put forward by the theologians. Throughout his trial, he declared his respect for a religion in which he had participated as a Dominican monk from 1565 to 1576, and then abandoned when he was found reading forbidden books. For he was even more resolute in his respect for the right of the enquiring, individual mind to follow, unimpeded, its search for truth. His famous last words in the public arena, warning his judges that they feared pronouncing his sentence more than he feared receiving it, anticipate a time when the rights of the philosopher and the rights of religion and theology would have nothing to fear, one from the other. The British Society for the History of Philosophy decided to commemorate Giordano Bruno in its summer conference of June 2000, in memory also of Brunos years in Elizabethan London, from 1583 to 1585, in which he wrote and published his six Italian dialogues, considered by many his philosophical masterpieces. The conference was held at University College London.

Renaissance philosophy was a less narrowly, or if one prefers a less rigorously defined, discipline than present-day philosophy, particularly of the Anglo-Saxon, analytic kind. For those such as Bruno, especially, who tended to be hostile to Aristotelian categories and to favour Neoplatonism, the boundaries of the discipline were thought of as open and unguarded by disciplinary police. Bruno himself declared more than once that the philosopher, the poet and the artist were all involved in the same search for truth, and he would often resort to poetry in the attempt to give expression to his most cherished and complex ideas. This interdisciplinary bent of Brunos own work was respected in the programme of the London conference, where professional philosophers were invited to speak together with literary scholars, historians of science and the arts, and intellectual historians or historians of ideas. The results can now be judged in the various and varied contributions to this volume, which offers a rich spectrum of approaches to multiple aspects of Brunos thought, as well as to his historical figure and reputation.

The papers published in this volume often differ considerably from the texts read at the conference itself. The contributors have put to good use the lively discussion of their subjects which developed both on the public platform and during the social events held throughout the conference. Both I and the British Society for the History of Philosophy are grateful to contributors for this enduring interest in, and meditation on, their chosen Brunian themes. We are grateful too for their participation in the conference to those few speakers who, for various personal reasons, have not presented their text for publication.

The conference itself also benefited from an exhibition of early printed editions of works by Bruno and his contemporaries, drawn from the Rare Books Library of University College London. Photographs from a selection of these titles have been chosen to illustrate the papers published here.

It is not the intention of this Preface to comment on the contributions to this volume, which is presented to the attention of its readers in the hope of making better known to an English-speaking public the work of whom many in continental cultures consider the major philosopher of the European Renaissance. But one exception must, sadly, be mentioned, for it transforms the volume into a double commemoration, not only of Giordano Brunos death, but also of the death, on 3 August 2001, of the distinguished editor and commentator of his works, Professor Giovanni Aquilecchia.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Giordano Bruno: Philosopher of the Renaissance»

Look at similar books to Giordano Bruno: Philosopher of the Renaissance. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Giordano Bruno: Philosopher of the Renaissance and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Bruno Skvorc [Bruno Skvorc] - Build Your First Ethereum DApp](/uploads/posts/book/119691/thumbs/bruno-skvorc-bruno-skvorc-build-your-first.jpg)