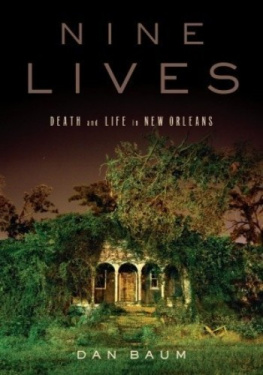

ALSO BY DAN BAUM

Smoke and Mirrors: The War on Drugs and the Politics of Failure

Citizen Coors: An American Dynasty

For the people of New Orleans

Contents

Oy! You ask someone in New Orleans a question, and they have to start so far back that they never get to telling you what you want to know!

MARGARET L. KNOX ,

F EBRUARY 24, 2007

New Orleans is still full of brigands, freebooters, mercenaries, and slaves.

JACQUES MORIAL ,

F EBRUARY 23, 2006

ABOUT THIS BOOK

UPDATED FOR THE PAPERBACK EDITION

M ost visitors to New Orleans sooner or later start asking impolite questions: Why has the rebuilding since Katrina gone so slowly? Why do you put up with such corrupt and incompetent politicians? How can you waste so much money on Mardi Gras when youre still living in trailers? Doesnt anybody in this city ever show up on time?

New Orleanians are hard to offend. Stop thinking of New Orleans as the worst-organized city in the United States, they often say. Start thinking of it as the best-organized city in the Caribbean.

That New Orleans is like no place else in America goes way beyond the food, music, and architecture. New Orleanians dont even understand such fundamentals as time and money the way other Americans do. The future, for example: While the rest of Americans famously dream and scheme and chase the horizon, New Orleanians are masters at the lost art of living in the moment. If were doing okay this minute, goes the logicenjoying one anothers company, keeping cool, and maybe having something good to eatof what earthly importance is tomorrow or next week? Given the fragility of life, why even count on getting there? New Orleanians are notoriously late showing up, if they show up at all, because by and large they dont keep calendars. Calendars are tools for managing the future, and in New Orleans the future doesnt exist.

As for money, New Orleanians like it well enough, but not so theyd bend their lives out of shape to get some. They have more time than money, and thats how they like it. Ambition isnt a virtue in the lowlands between Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River. New Orleanians tend to identify more with the welfare of their families, neighborhoods, wards, bands, krewes, second-line clubs, and Mardi Gras Indian tribes than with their own personal achievement, so are largely free of the insatiable desire for individual aggrandizement that afflicts the rest of us. To the extent Americans strive to make their tomorrows brighter than today, New Orleanians really want nothing more than for everything to stay the same.

Long before the storm, New Orleans was by almost any metric the worst city in the United Statesthe deepest poverty, the most murders, the worst schools, the sickest economy, the most corrupt and brutal cops. Yet a poll conducted a few weeks before the storm found that more New Orleaniansregardless of age, race, or wealthwere extremely satisfied with their lives than residents of any other American city. When Katrina made a blank slate of the city, several high-level commissions promoted plans to make New Orleans bigger and better than it was before. All of them failed completely. Some people rejected bigger and better as code for whiter, but even more, I suspect, heard bigger and better as a recipe for a city driven by the dollar and the clock. Who needs that?

While covering Katrina and its aftermath for The New Yorker, I noticed that most of the coverage, my own included, was so focused on the disaster that it missed the essentially weird nature of the place where it happened. The nine intertwined life stories offered here are an attempt to convey what is unique and worth saving in New Orleans. None of these people is famous. Only one is a public official, and he but a minor one. The rest toil pretty much in obscurity. Their lives, though, would be unimaginable anyplace else, and its New Orleans itselfperpetually whistling past the graveyardthat is the real protagonist here.

These nine people do not all end up sitting on the same flooded rooftop. Nothing in New Orleans is ever that tidy. Besides, no single rooftop would have harbored both a millionaire king of carnival from the Garden District and a retired streetcar-track repairman from the Lower Ninth Ward, a transsexual bar owner from St. Claude Avenue and the jazz-playing parish coroner, a white cop from Lakeview and a black jailbird from the Goose. But thats not to say these lives dont touch one another. New Orleans is a small city. Some of these stories do intersect. And even the ones that dont come in physical contact share a common problem: how to live in a place that, by the go-go rules of modern America, has no right to exist. In the context of the techno-driven, profit-crazy, hyperefficient United States, New Orleans is a city-sized act of civil disobedience.

These stories come to the reader through two filters. The sensibilities, emotions, and memories of the nine principal characters color them most of all. They all sat for many hours of interviews, unpacking their innermost moments for a stranger, with nothing to gain but the very New Orleanian pleasure of storytelling. Although I supplemented those interviews by talking to many of my characters friends, relatives, and associates, I chose to recount these nine peoples lives from their own points of view. They invited me into their heads and hearts, so that seemed the best place from which to tell their stories.

It is certain that other people will remember the events described herein differently. And memory is a funny thing. Frank Minyard, for example, described to me in detail the epiphany that launched him in the direction of becoming Orleans Parish coroner. While he was sure it happened in 1967, he was equally sure the song that set it off was Peggy Lees Is That All There Is? which wasnt recorded until 1969. But this was how Franks own story explained Franks world to Frank. So I left it as he told it.

The second filter is my own. I have re-created scenes and dialogue out of remembered snippets, using what I knew about the people, the time, the immediate setting, and the city. I put words to thoughts and feelings that, during the months I spent working on this, were laid bare by these remarkably candid people. I changed the names of three peripheral characters to avoid hurting their feelings.

It turns out that a book written from the reminiscences of nine people is a breathing, changing organism. After the hardcover was published in February 2009, some of my protagonists spoke up with changes they wanted to see in later editions. Most were smallnames misspelled, clothing details bungled, and a reference to forsythia when any fool knows that forsythia doesnt grow in New Orleans. One of the nine was appalled that a story intended to be off the record showed up in print, though upon reflection decided (in a very New Orleans way) what the hell, leave it as it stands. But another of the nine came back to say that a couple of anecdotes didnt happen at all the way Id told them, and that was a puzzler. My wife and I both remembered being told the stories, but our notes were ambiguous. Finally, we decided to make the requested changes for this edition of Nine Lives. The stories herein, after all, belong to these nine remarkable people. My goal all along was to tell them as accurately as possible.